Why do soft drinks go flat?

It has to do with escaping carbon dioxide.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The bubbles in soda pop have tickled taste buds for centuries. However, all good things fizzle out and eventually soda's effervescence goes flat. But why?

It turns out that gas in the beverages forces the bubbles out.

Carbonated drinks fizz because bubbles of carbon dioxide are infused within the liquid during production. "It's dissolved the same way sugar and salt can dissolve into water," Mark Jones, a chemistry consultant and fellow of the American Chemical Society, told Live Science.

Carbon dioxide, or CO2, is about 1.5 times heavier than air, according to the Columbia Climate School at Columbia University in New York City. Based on that fact alone, you might not expect CO2 to rise into the air.

Related: Why does eating pineapple make your mouth tingle?

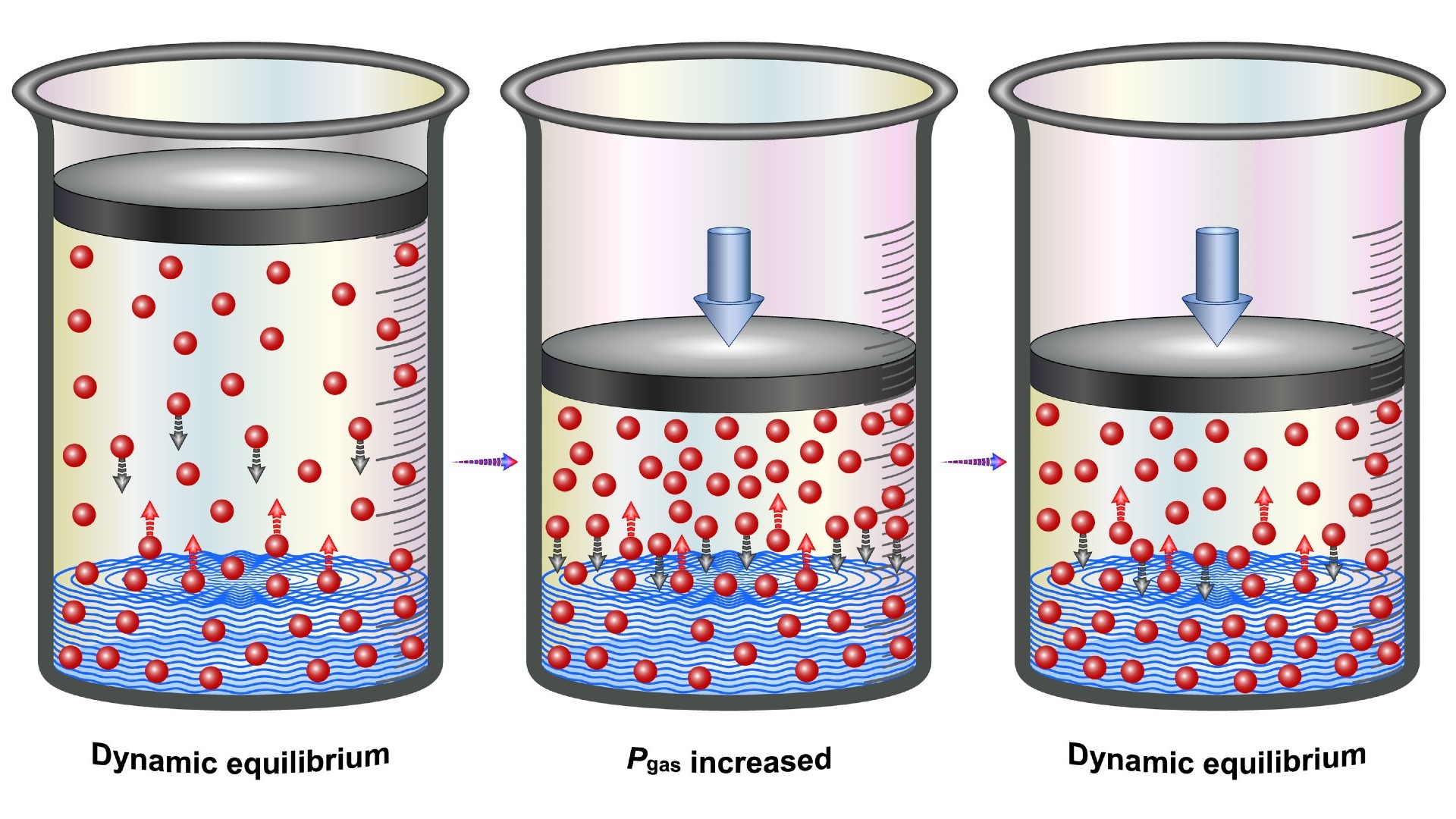

However, soda starts off super-saturated with carbon dioxide. As a result, due to a principle in physical chemistry known as Henry's law, the gas experiences pressure that makes it want to escape from the soda. British chemist William Henry proposed Henry's law in 1803, according to Britannica. Henry's law states that the amount of a gas dissolved within a liquid is proportional to the pressure of that same gas in the liquid’s surroundings. This law influences whether a gas enters a liquid or exits it.

When soda is bottled or canned, the space above the drink is usually filled with carbon dioxide at a pressure slightly above that of standard atmospheric pressure (about 14.7 pounds per square inch or 101.325 kilopascals), Joe Glajch, an analytical chemist and chemistry consultant with 40 years of experience in the chemistry and pharmaceutical industries, told Live Science. As such, because of Henry's law, the carbon dioxide within the beverage stays within the fluid.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When a soda is first opened, this pressurized carbon dioxide is released into the air. "This escaping gas results in the hiss one expects from a new soda," Glajch said.

Carbon dioxide makes up about 0.04% of Earth's atmosphere, according to Columbia University's Climate School. When soda is left exposed to air, Henry's law suggests the carbon dioxide in the soft drink naturally wants to reach the same concentration in the fluid as it is in the air.

As such, "when a can or bottle of soda has sat around open a long time, the carbon dioxide dissolved inside it eventually bubbles out — it will want to come into equilibrium with the carbon dioxide in the outside air," Jones said. "When the soda is less fizzy, we call it flat."

Shaking a soda can or bottle will make the soda go flat more quickly by helping the carbon dioxide within it escape. Shaking mixes air in the empty space of the bottle or can with the rest of the liquid, resulting in bubbles. These bubbles can then serve as sites of nucleation, or spots where atoms and molecules can cluster together — a bit like how dust in the air can help snowflakes form.

The nucleation sites lead tiny bubbles of carbon dioxide in the soda to join together. The resulting larger bubbles can more easily escape the liquid's surface tension, which is the energy needed for liquid molecules to separate from each other, Jones said.

"The same thing happens if you were to drop in a teaspoon of salt or sugar," Glajch said. "The solid powder grains act as sites of nucleation, making the soda fizz" as the carbon dioxide escapes.

Originally published on Live Science on Feb. 4, 2013 and rewritten on June 8, 2022.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus