Big Bird Left Big Droppings

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

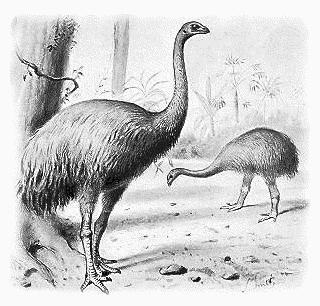

Giant birds camping out in caves and rock shelters thousands of years ago left behind enormous feces, reaching nearly half a foot in length. The preserved poop reveals what the now-extinct birds munched on so long ago.

The fossilized feces — more than 1,500 pieces — were discovered beneath cave floors and rock shelters in remote areas across southern New Zealand. The feces primarily came from species of the extinct giant moa, flightless birds that weighed up to 550 pounds (250 kg) and stood at nearly 10 feet (three meters).

The researchers analyzed some of the feces thought to belong to moa due to the large size, picking through the defecated material for bits of plants, seeds and leafy material. DNA analyses found some of the feces came from at least four moa species, including the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus), upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), heavy-footed moa (Pachyornis elephantopus) and stout-legged moa (Euryapteryx gravis).

The researchers suggest all moa were probably eating a variety of plants, dominated by herbs and sub-shrubs (shrubs less than about 3 feet, or 1 meter, tall).

"Surprisingly for such large birds, over half the plants we detected in the feces were under 30 centimeters (1 foot) in height," said study researcher Jamie Wood of the University of Otago in New Zealand. "This suggests that some moa grazed on tiny herbs, in contrast to the current view of them as mainly shrub and tree browsers."

He added, "We also found many plant species that are currently threatened or rare, suggesting that the extinction of the moa has impacted their ability to reproduce or disperse."

Feces recovered in the same area likely came from other extinct birds, including the South Island goose (Cnemiornis calcitrans) and Finsch's duck (Chenonetta finschi).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When animals shelter in caves and rock shelters, they leave feces which can survive for thousands of years if dried out," said study researcher Alan Cooper of the University of Adelaide in Australia. "Given the arid conditions, Australia should probably have similar deposits from the extinct giant marsupials. A key question for us is, 'Where has all the Australian poo gone?'"

The research is published in the December issue of the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

- 10 Amazing Things You Didn't Know About Animals

- Bird News, Information and Images

- Images: Rare and Exotic Birds

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus