Facts About Phosphorus

Phosphorus, the 15th element on the periodic table, was first distilled by an alchemist searching for gold — searching, that is, in at least 60 buckets of urine.

Hennig Brand, a German, discovered phosphorus quite by accident in 1669 while processing urine in search of a compound that would turn ordinary metals into gold. According to the Jefferson National Linear Accelerator Laboratory, there would have been an easier way: Phosphorus is now mostly isolated from the rock phosphate.

There's even a 1795 painting devoted to phosphorus' discovery, titled "The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher's Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers." (The Philosopher's Stone is the mythical substance said to turn metals into gold.)

The painter, Joseph Wright, left out some of the details, as recorded in the 1796 paper "Phosphoros Elementals" and re-described in the 2006 textbook "Chemistry" by Kenneth Whitten and colleagues. The first step in the process was to steep the urine for two weeks, until it putrefied and bred worms.

Just the facts

According to the Jefferson Lab, the properties of phosphorus are:

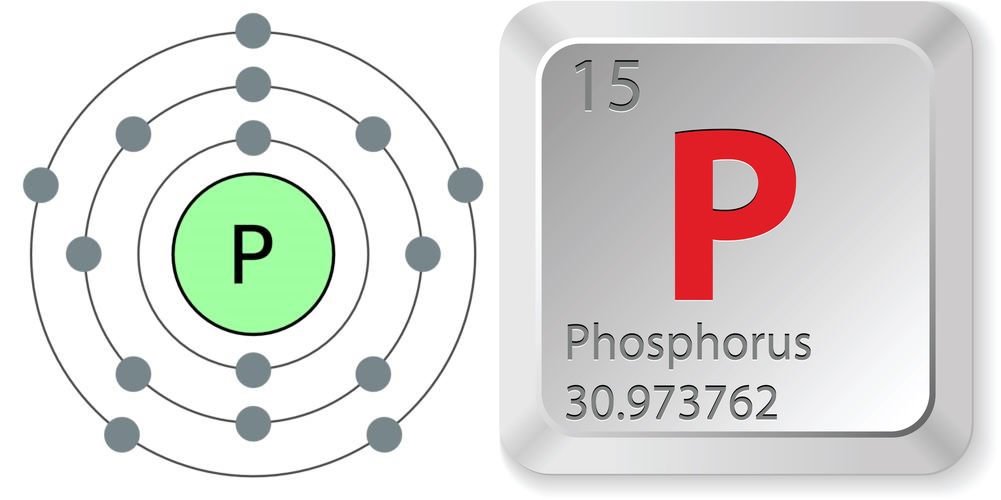

- Atomic number (number of protons in the nucleus): 15

- Atomic symbol (on the Periodic Table of Elements): P

- Atomic weight (average mass of the atom): 30.973762

- Density: 1.82 grams per cubic centimeter

- Phase at room temperature: Solid

- Melting point: 111.57 degrees Fahrenheit (44.15 degrees Celsius)

- Boiling point: 536.9 F (280.5 C)

- Number of isotopes (atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons): 22; 1 stable

- Most common isotopes: Phosphorus-31 (100 percent natural abundance)

Element of light

The world phosphorus comes from a Greek word meaning "bearer of light," and this element delivers on that promise. The most common forms are white phosphorus, made up of phosphorus atoms arranged like a tetrahedron (a four-sided pyramid), and red phosphorus, a solid but non-crystalline form of the element. Less common is black phosphorus, which is made of atoms arranged in a ring structure and looks a bit like the graphite at the point of a pencil.

White phosphorus is waxy and gives off a slight glow in air, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry. It's also capable of self-igniting in air once the temperature reaches about 86 F (30 C); the only safe storage is under water. As a result, white phosphorus is used in fireworks and weaponry. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it smells like matches or garlic. Inhalation or contact with the skin is toxic, causing burns that can quickly turn fatal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Red phosphorus is far more stable at room temperature — in fact, it's found on the side of any box of safety matches. The friction of the match against the red phosphorous transforms a little bit of the red phosphorus into white phosphorus, providing the ignition needed to light the match, according to Michigan State University's Science Theater. Red phosphorus is made by heating white phosphorus under controlled conditions.

In certain combinations, though, red phosphorus is still very dangerous. When exposed to enough heat (500 F or 260 C), it will ignite. It explodes when combined with other compounds such as chlorine, sodium and ammonium nitrate, according to California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, which flags red phosphorus as one of the dangerous ingredients used in making methamphetamines.

The non-illicit uses of phosphorus include steel-making and the production of flares. The most common use, however, is in fertilizers, according to the RSC. Despite its fiery properties, phosphorus is crucial to life. As phosphate, a charged molecule, it combines with sugar to form the backbone of DNA. It's also part of adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the molecule that stores and releases energy to allow cells to function.

Who knew?

- There are about 26.5 ounces (750 grams) of phosphate in the average human body, mostly in the bones, according to the RSC.

- Earth may be approaching "peak phosphorus," after which the element will be harder and harder to mine. Mineral reserves of phosphorus are estimated to last between a few decades and 300 years at the most. Increasingly rare and expensive phosphorus would throw the global agriculture system into disarray, experts worry.

- Strike-anywhere matches can ignite on any surface because they contain a small amount of white phosphorus built in to the match head.

- Meteorites may have brought phosphorus to Earth, according to a 2013 study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. By 3.5 billion years ago, the element was abundant on the planet, the study found.

- Phosphorus can be used as a warning signal for heart disease. According to a 2009 study in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, higher blood-phosphorus levels indicate higher rates of calcification of the coronary arteries.

Current research

Human phosphorus use has created problems for wildlife and people, alike. In August 2014, the city of Toledo, Ohio, had to warn citizens against using the city's water due to a toxic algae bloom. Such blooms, which occur in other drinking-water lakes across the country as well, are often caused or exacerbated by phosphorus from fertilizers and livestock waste flowing into waterways.

In many streams and lakes, "phosphorus is the nutrient that is the most scarce, and therefore it is often the most important nutrient," said Dan Obenour, a professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at North Carolina State University.

Obenour and his colleagues have studied the algae blooms of Lake Erie, which is where Toledo gets its drinking water. The dominant source of phosphorus running into the lake is from agricultural fertilizers, Obenour told Live Science, though lawn fertilizers, pet waste and even treated wastewater contribute.

Other factors, such as water temperature, can influence the timing and size of toxic algae blooms, so Obenour and his colleagues wanted to isolate the effects of fertilizer runoff. They used computer models to relate the amount of phosphorus flowing into Lake Erie to the size of the late-summer algae blooms in the lake.

The results, published in October 2014 in the journal Water Resources Research, showed a link: The more phosphorus early in the year, the larger the algae bloom in late summer. What's more, Obenour said, "the lake is becoming more sensitive to cyanobacteria [algal] blooms."

In other words, less phosphorus is necessary to create ever-larger blooms — a fact that could influence regulations on agriculture upstream from the lake. The reason for the increased sensitivity remains somewhat mysterious, but invasive species could be one factor, Obenour said. Invasive zebra and quagga mussels feed on non-toxic algae that compete with the toxin-generating cyanobacteria. Thus, when a rush of phosphorus enters the lake, toxic algae have little competition in gobbling it up. The algae blooms would likely be a quarter or less the size of the peak blooms seen in Lake Erie in 2011 without human influence, Obenour said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Additional resources

- Royal Society of Chemistry: Phosphorus

- Jefferson Lab: The Element Phosphorus

- The Derby Museum's Joseph Wright Gallery features the painting "The Alchymist …"

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.