Tropical Ice Reveals Rare Climate Record

A new and rare ice core record of tropical temperatures highlights changes in the enfants terribles of world climate, the El Niño/La Niña–Southern Oscillation.

The climate record comes from Peru's stunning Cordillera Oriental mountain range, home to Quelccaya, the world's largest tropical ice cap. Researchers trekked to an altitude of more than 18,000 feet (5,600 meters) to probe the ice.

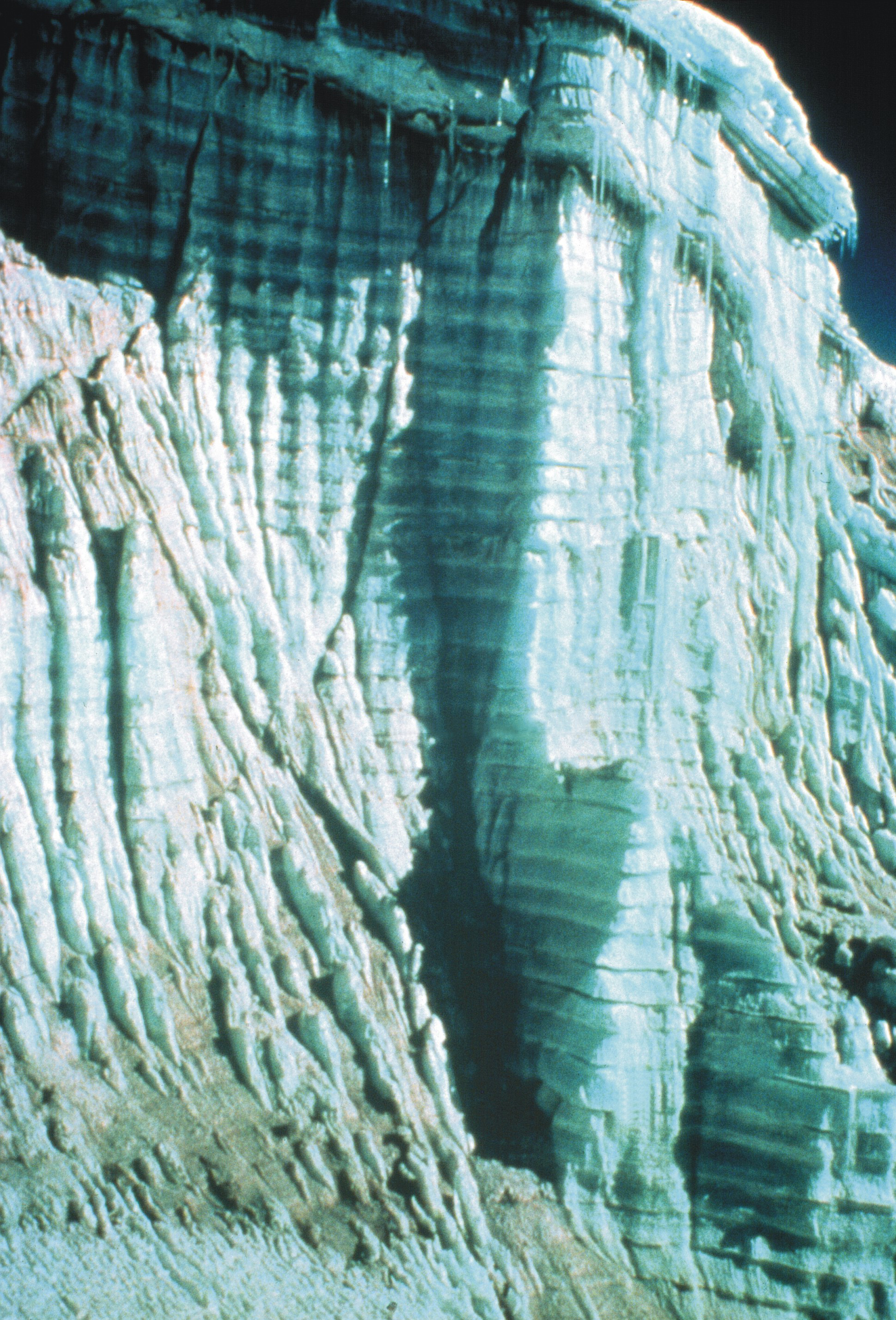

The two ice cores (or cylinders of ice) drilled from the Quelccaya hold 1,800 years of climate history, according to a study published today (April 4) in the journal Science Express. Alternating light and dark layers record the wet and dry seasons at the top of the world — light from snow and dark from dust during the dry season.

"We have an annual resolution going back 1,300 years, and that's almost unprecedented," said Ellen Mosley-Thompson, a paleoclimatologist at Ohio State University and study co-author. Only a few ice cores from polar regions have longer annual resolutions, she said. (This resolution means they can see what the climate was like for each year.)

Big climate patterns

Ice cores draw the attention of climate researchers because the ratio of oxygen isotopes in the ice acts like a thermometer for past climate and sea surface temperatures. Isotopes are atoms with different weights due to different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei.

One notable climate event in the ice cores is the Little Ice Age, which chilled these tall mountains from 1520 to 1880. In northern latitudes, the cooling froze New York City's Harbor and the Thames River in England. In South America, trace elements such as ammonium and nitrate in the ice indicate the Amazon was moist, because they reflect increased microbial activity in the soil, Mosley-Thompson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though most of the moisture for the glacier's snowfall comes from the east, rising from the Amazon, wet El Niño years also contribute, Mosley-Thompson said.

In the past 140 years, warm pools of water in the Pacific Ocean shifted, reflecting changes in the El Niño and the Intertropical Convergence Zone, the study found. The zone, which is a key component of global atmospheric circulation, has migrated northward, according to the ice core record.

"The Intertropical Convergence Zone is like the hydrologic equator. It's very critical to who gets water and who doesn't, so it's very useful to look back in the records and see how it's moved," Mosley-Thompson told OurAmazingPlanet.

The Quelccaya Ice Cap has shrunk 985 feet (300 meters) since the researchers first climbed to the glacier in 1983. Plants exposed by the retreating tropical ice in 2011 were carbon-dated to 6,298 years ago the study reports.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.