Tropical Rainfall Moving North

Updated 8:53 a.m. ET 7/2.

Earth's most prominent rain band, near the equator, has been moving north at an average rate of almost a mile (1.4 km) a year for three centuries, likely because of a warming world, scientists say.

The band supplies fresh water to almost a billion people and affects climate elsewhere.

If the migration continues, some Pacific islands near the equator that today enjoy abundant rainfall may be starved of freshwater by midcentury or sooner, researchers report in the July issue of the journal Nature Geoscience.

"We're talking about the most prominent rainfall feature on the planet, one that many people depend on as the source of their freshwater because there is no groundwater to speak of where they live," said Julian Sachs, associate professor of oceanography at the University of Washington and lead author of the paper. "In addition many other people who live in the tropics but farther afield from the Pacific could be affected because this band of rain shapes atmospheric circulation patterns throughout the world."

Water shortage?

While water is increasingly becoming a hot commodity around the globe, there is no global water shortage. Human demand for water has tripled in the past 50 years, by some estimates. Yet Earth has essentially as much water now as ever — about 360 quintillion gallons.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rather, human populations put ever more pressure on local and regional water resources, which in some cases — such as the American Southwest — are dwindling with climate change. The water still exists, it just gets dumped elsewhere.

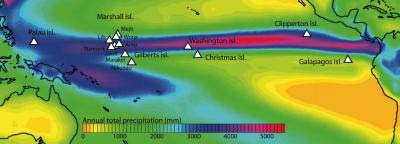

The band of tropical rainfall is created at what scientists call the intertropical convergence zone. There, just north of the equator, trade winds from the northern and southern hemispheres collide where heat pours into the atmosphere from the tropical sun. Rain clouds up to 30,000 feet thick dump as much as 13 feet (4 meters) of rain a year in some places.

The amount of rain in the zone actually increased between 1979 and 2005, this video shows.

The band is thought to have hugged the equator 350 years ago, during the planet's Little Ice Age (roughly 1400 to 1850).

From dry to downpours

The authors analyzed natural records of rainfall (including microbes and chemical ratios) left in annual layers of lake and lagoon sediments from four Pacific islands at or near the equator.

Washington Island, about 5 degrees north of the equator, is now at the southern edge of the intertropical convergence zone and receives nearly 10 feet (2.9 meters) of rain a year. But during the Little Ice Age it was arid. A similar arid past was found for Palau, which lies about 7 degrees north of the equator and in the heart of the modern convergence zone.

In contrast, the researchers present evidence that the Galapagos Islands, today an arid place on the equator in the Eastern Pacific, had a wet climate during the Little Ice Age.

"If the intertropical convergence zone was 550 kilometers, or 5 degrees, south of its present position as recently as 1630, it must have migrated north at an average rate of 1.4 kilometers — just less than a mile — a year," Sachs said in a statement. "Were that rate to continue, the intertropical convergence zone will be 126 kilometers — or more than 75 miles — north of its current position by the latter part of this century."

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Gary Comer Science and Education Foundation.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus