Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The saying that it's impossible to step into the same river twice may be true, at least as far as the brain is concerned.

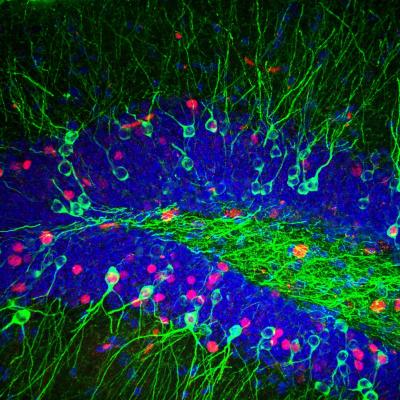

Different neurons in a brain region called the dentate gyrus fire when encountering a place for the first or second time. Different brain cells also fire to distinguish subtle changes in familiar terrain, new research in mice suggests.

The findings, which were published March 20 in the journal eLife, may help unravel how the brain tracks minute changes in our everyday environments, a process known as pattern separation. The phenomenon is how we find our car keys or wallet, for instance.

"Everyday, we have to remember subtle differences between how things are today, versus how they were yesterday, from where we parked our car to where we left our cellphone," said study co-author Fred H. Gage, a neuroscientist at the Salk Institute, in a statement. "We found how the brain makes these distinctions, by storing separate 'recordings' of each environment in the dentate gyrus." [10 Odd Facts About the Brain]

Small differences

Several studies suggested that a brain region called the hippocampus helps people navigate and orient themselves in space, in part by retrieving memories from different environments. For instance, London cabbies have more hippocampal grey matter after training in navigation.

But exactly how the hippocampus sifted memories of new and familiar places wasn't fully understood.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Previous studies found that a sub-region of the hippocampus, called the dentate gyrus, helped the brain pick out important patterns from detail-rich memories of the environment — such as where someone placed their keys from one day to the next. The same region may play a role in the eerie feeling of déjà vu.

Different brain cells

To find out, Gage and his colleagues measured firing from neurons, or brain cells, in mice as they navigated a new chamber.

They then recorded their brain activity while the same mice explored either the exact same chamber or a very similar one.

The team found that neurons in a sub-region of the hippocampus called CA-1 fired when mice were in both new and familiar environments. But in the dentate gyrus, different groups of neurons fired in undiscovered territory versus familiar spaces. Different collections of cells also fired in the dentate gyrus in the two similar chambers.

The findings suggest the neurons that encode our memories of a new place are different from those that fire when we revisit it and notice its subtle transformations.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus