Historic California Quake Released Surprising Energy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The rugged hills where Cary Grant sought his fortune in the 1939 film "Gunga Din" were also the scene of one of California's biggest earthquakes.

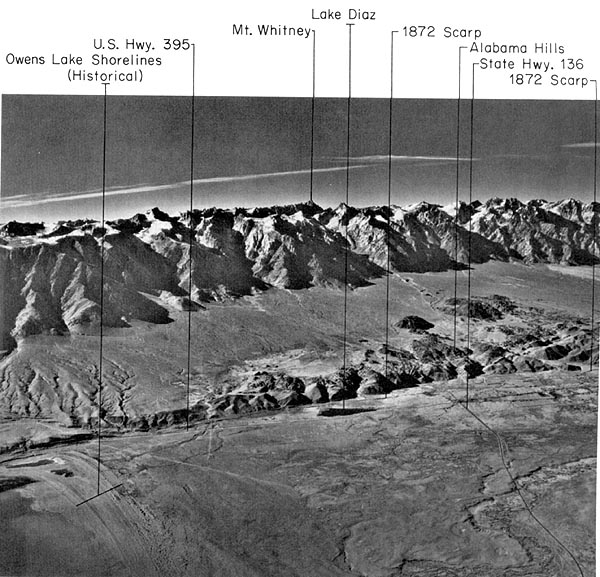

The Alabama Hills stood in for the Himalayas in "Gunga Din." Their massive boulders pop out of a long, narrow valley between the towering Sierra Nevada mountains to the west and the Inyo Mountains to the east.

The Owens Valley fault runs just east of the Alabama Hills. On March 26, 1872, around 2:10 a.m. local time, a massive earthquake on the fault shook the West from San Diego to Salt Lake City. The quake's energy was comparable to the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake on the San Andreas Fault, according to a 2008 study by the U.S. Geological Survey.

Now, a new study of the historic quake reveals an intriguing difference between the two great temblors. The Owens Valley fault broke along 70 miles (113 kilometers) of fault, less than one-half to one-third of the sections ruptured by the San Andreas Fault's biggest earthquakes, said Colin Amos, a geologist at Western Washington University in Bellingham and lead study author.

"Despite its short length, the Owens Valley quake seemed to have very energetic shaking," Amos said. The findings appear in today's (March 20) issue of the journal Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Continental quakes

On first principle, geoscientists assume the length a fault break relates to the energy of an earthquake. So the short but powerful Owens Valley temblor presents a quandary. Perhaps the stronger continental rocks transmit shaking more easily, or the longer interval between earthquakes there means more energy is released with each quake, Amos said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discrepancy also highlights a growing awareness among geoscientists of the difference between earthquakes along plate boundaries, such as the San Andreas, and within continents, or so-called intraplate earthquakes, like the Owens Valley quake.

The San Andreas Fault marks the boundary between two of Earth's tectonic plates, triggering massive earthquakes every couple hundred years. But in Eastern California, big earthquakes seem to link up several smaller faults when they strike, instead of staying on one fault. The quakes also repeat much less frequently, on the order of tens of thousands of years.

"There are a lot of faults out there that we don't know how they connect up in an earthquake rupture," Amos told OurAmazingPlanet. "Owens Valley is a historical example of that."

Amos and his colleagues dug trenches across the possible fault south of the Owens Valley rupture, to test if the fault broke farther than previous workers had thought. The researchers found no evidence of faulting in 1872, but they did see signs of a huge earthquake about 25,000 years ago. [13 Crazy Earthquake Facts]

"We certainly don't rule out the possibility that other faults nearby were active, but at least the biggest, more likely candidate does not appear to have rupture," Amos said.

The team is now scanning the Owens Valley fault with lidar, a laser-scanning technique that measures the surface elevation to within a few inches. This will reveal more detail about the fault's rupture.

"If we have to worry about lots of different smaller fault segments that could link up and if the energetics are really strong, that gives us more impetus to know more about them," Amos said.

Memories by Muir

A memorial along U.S. Highway 395 stands near a mass grave for the victims of the 1872 Owens Valley quake near the town of Independence. There were some 60 fatalities in total, mainly from collapsed adobe buildings.

Naturalist John Muir felt the earthquake waves pass through Yosemite Valley and wrote about the shaking's effect on the steep cliffs.

"The Eagle Rock on the south wall, about a half a mile up the Valley, gave way and I saw it falling in thousands of the great boulders I had so long been studying, pouring to the Valley floor in a free curve luminous from friction, making a terribly sublime spectacle — an arc of glowing, passionate fire, fifteen hundred feet span, as true in form and as serene in beauty as a rainbow in the midst of the stupendous, roaring rockstorm."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus