Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

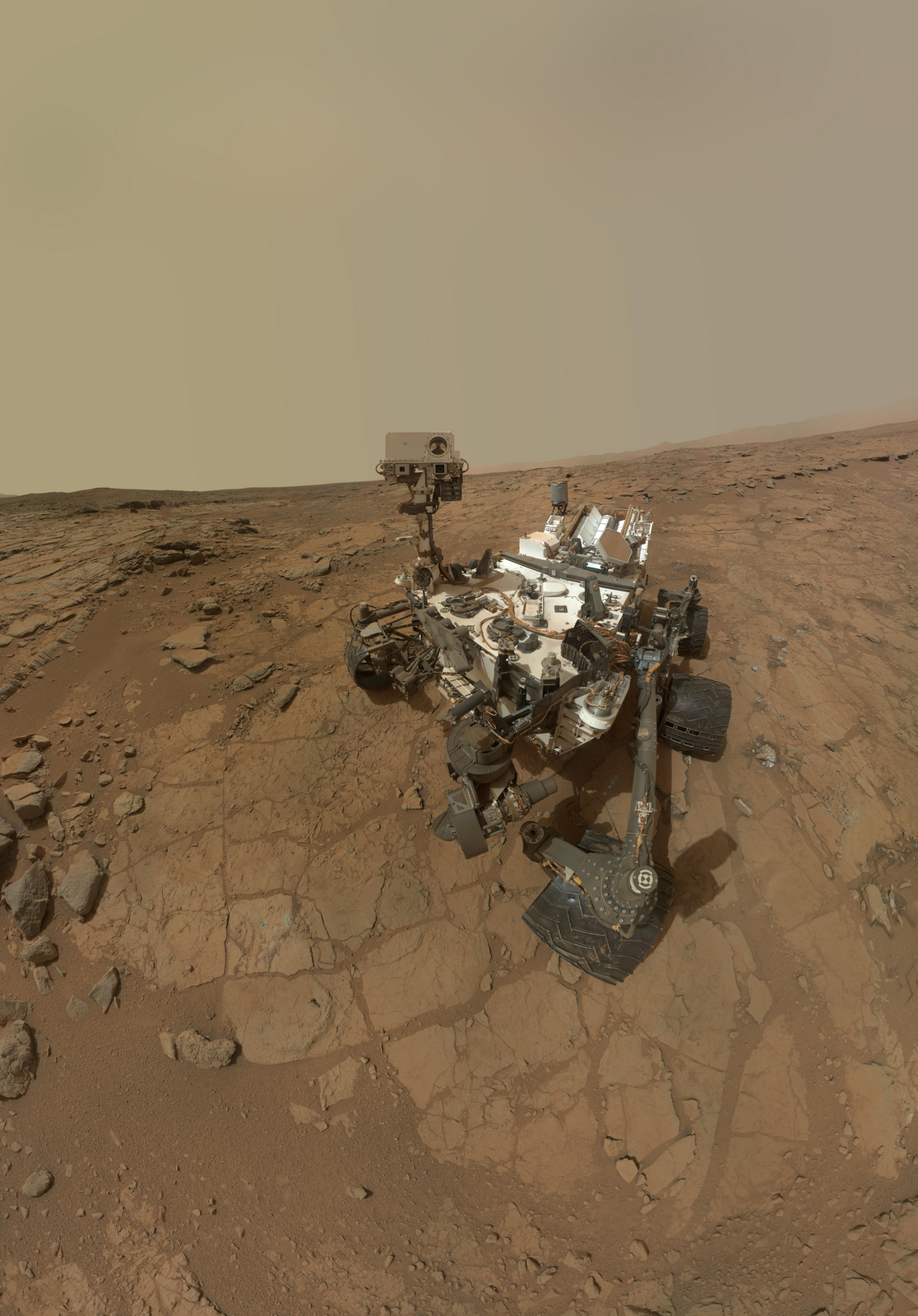

A huge mountain miles away is beckoning NASA's Mars rover Curiosity, but the 1-ton robot won't begin the long trek for at least another few months.

Curiosity's ultimate destination is the base of 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp, which lies about 6 miles (10 km) away. But the rover will remain at its current location — a spot called Yellowknife Bay, which mission scientists say could have supported microbial life long ago — until May at the earliest, team members said.

The rover has more work to do at Yellowknife to help researchers firm up their assessments of the area's past habitability on Mars. And these efforts will be complicated by a computer glitch Curiosity is fighting through, as well as an unfavorable planetary alignment that will make communicating with the robot difficult for most of April, officials said.

A habitable ancient environment

Last month, Curiosity drilled 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) into a Yellowknife Bay outcrop known as "John Klein" — deeper than any Mars robot had ever gone before.

Analysis of the resulting samples determined that the area was once a benign aqueous environment, such as a neutral-pH lake. Curiosity's instruments also detected many of the chemical ingredients necessary for life as we know it, including sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon. [The Search for Life on Mars (Photo Timeline)]

The mission team thus announced on Tuesday (March 12) that Yellowknife Bay could have supported microbes billions of years ago, if such life-forms ever evolved on Mars or were transported there.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Like most scientists, Curiosity's handlers aren't content with a sample size of one. They want to drill a second hole into the John Klein outcrop in an attempt to solidify and expand upon what they've already discovered. But this operation will have to wait, for two reasons.

First of all, Curiosity has still not fully recovered from a glitch that knocked out its main, or A-side, computer in late February. Curiosity is now running on its backup computer while engineers investigate the problem, but the robot has not yet resumed full science operations.

And even if the Curiosity rover gets a clean bill of health soon, an impending "solar conjunction" — in which the sun comes between Earth and Mars — will complicate matters further, NASA officials said.

"Basically, we can't talk to the rover and the rover [can't] talk to us for most of the month of April," Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA's Mars Exploration Program, said during a press conference Tuesday. "We will not do another drilling, the second drill hole, until after solar conjunction. So we're not going to start that activity until May."

Mysterious Mount Sharp

The discoveries Curiosity has made near its landing site have delayed its departure for Mount Sharp, but the rover team remains committed to trekking to the huge mountain.

Mount Sharp's lower reaches show signs of long-ago exposure to liquid water, and its many layers preserve a record of Mars' changing environmental conditions over time. Mission scientists hope to read this record like a book as Curiosity climbs through the mountain's foothills.

Exactly when the rover will begin the 6-mile journey to Mount Sharp will depend on what happens during and after the second drilling operation, scientists said.

"If it continues to look promising, we'll do some more work. If not, we'll get on the road," said Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, a geologist at Caltech in Pasadena. "We'll probably clean up business with a few things that we pass by to help characterize the overall broad environment, but our decision as a team is to finish up here at John Klein, and then hit the road to Mount Sharp."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus