Book Worms? Medieval Tomes Hold Surprising Fossil Record

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A smattering of white spots found among the ink in medieval books aren't just printing errors — they're actually an amazingly detailed "fossil" record of European beetles, new research finds.

The dots represent spots, or wormholes, where hatching beetles chewed their way out of the woodblocks used to print art and illustrations between the 1400s and 1800s.

This literary record reveals that two species that now overlap in Western Europe once kept their distance from each other along the entire continent. Without evidence of the wormholes, this history would have been impossible to discern, said study researcher Blair Hedges, a biologist at Pennsylvania State University.

Article continues below"All of these findings about the distribution were from the wormholes," Hedges told LiveScience. "There were no specimens in jars or, in this case, pinned or anything. There was just no information that we had."

Biological bookworms

European printers started using woodcuts, or carved wood blocks, to produce printed illustrations in the 1400s. (By then, that craft was already centuries-old in Japan and other parts of Asia.) Hardwood with a fine grain was typically used for the carved blocks, which would then be inked like rubber stamps to produce an image on paper or fabric.

Unfortunately for bookmakers but luckily for modern biologists, hardwoods such as box, pear or apple are a favorite of certain species of beetle, which leaves its larvae in the wood to pupate. Once the larvae grow into beetles, they gnaw their way out, leaving distinctive round holes that vary in size depending on the species. [See images of the damaged woodcuts]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such was the fate of many a woodcut left in storage. Between the first edition and later printings, more and more round white dots would appear in books, Hedges said, corresponding with the beetle infestation of the woodcut. These proliferating marks provide a sort of non-stone fossil record of where beetles lived at any given time.

"It's very hard to get that kind of detailed information," Hedges said. "These are about the best fossils you could ever hope to find, and that is fossils with exact dates, like 1498, in exact locations, like Paris or Amsterdam."

Fossil record, in print

By surveying medieval tomes in library collections and in online high-resolution digital archives, Hedges was able to measure the white spots. In 473 prints dating from 1462 to 1899, he found thousands of spots, including 3,263 perfectly round holes created when beetles exited the wood block and 318 meandering "tracks" created as beetles chewed their way along the wood grain. This kind of left-behind evidence of living organisms is called trace fossils.

In books printed in northern cities such as London, the holes tended to be small, averaging about 0.06 inches (1.44 millimeters) across. In southern European cities, they were larger, averaging about 0.09 inches (2.3 mm) across. Distinctive tracks also gave away southern species.

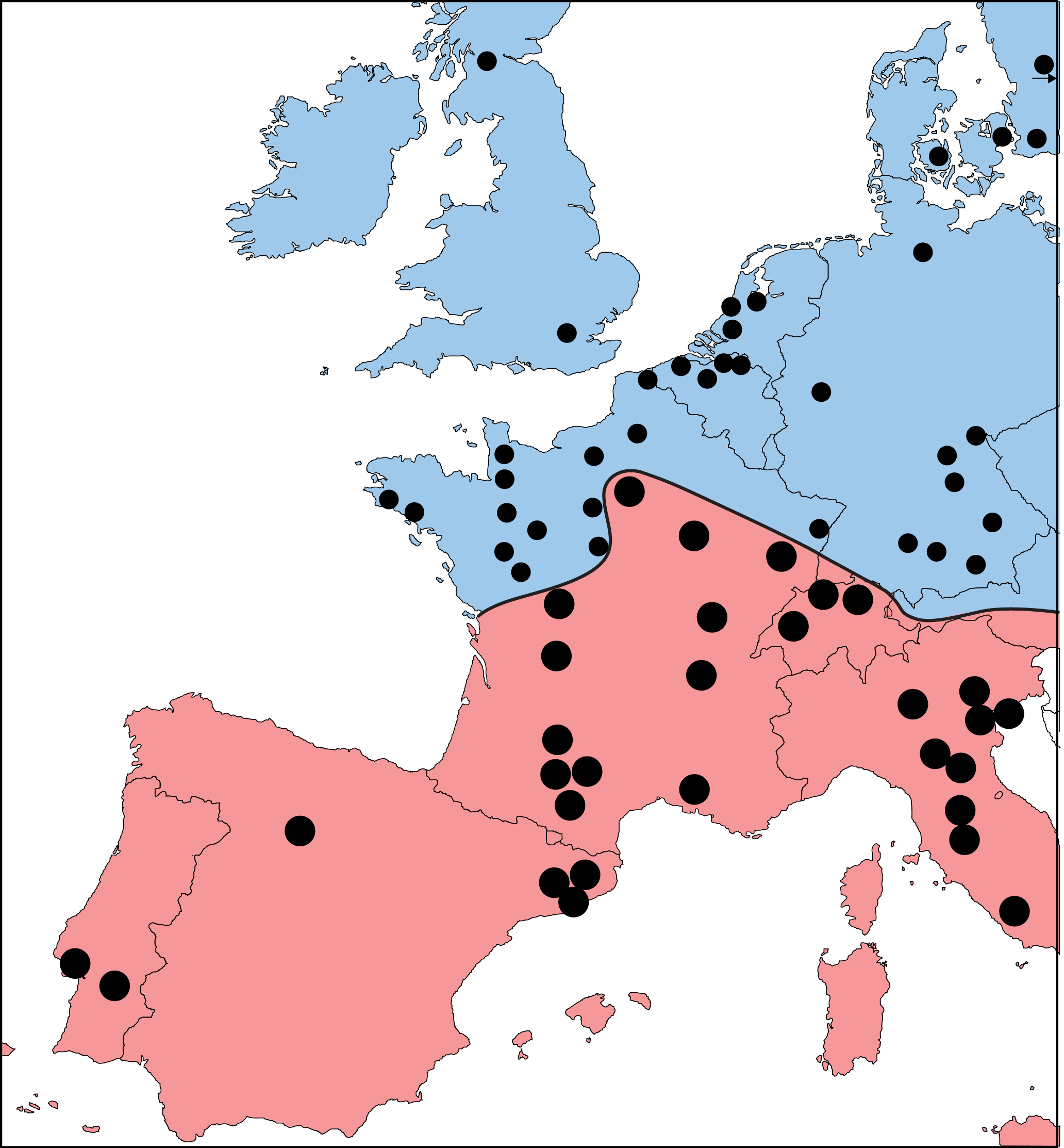

These measurements reveal that in the north, the woodcut-chewer was the common furniture beetle (Anobium punctatum). In the south, the Mediterranean furniture beetle (Oligomerus ptilinoides) was the culprit. Surprisingly, the two never met. They stayed on either side of a line that cut across France, hugged the border between Switzerland and Germany and then followed the boundary between Italy and Austria.

"There was no gap in between," Hedges said. "They literally came right up to each other, certainly within miles. I could not find any evidence that they overlapped."

That sort of boundary is very unusual in species distribution, he said. Because climate varied over those 500 years, the stable border between northern and southern species probably had to do with the fact that both beetles prefer the same kind of wood.

"They were trying to avoid competition, so they weren't overlapping," Hedges said.

Today, with increased trade in furniture and lumber, both beetles are found throughout Western Europe. In Eastern Europe, the situation looks a little more complex, Hedges added. And he hasn't even had time to get into American woodcuts or other regions of the world.

"Japan and China did woodcut printing even earlier than Europe," he said. "There's a lot of potential for discovering other species and other interactions."

Hedges published the findings today (Nov. 20) in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus