Goo Makes Flu Worse in Winter

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

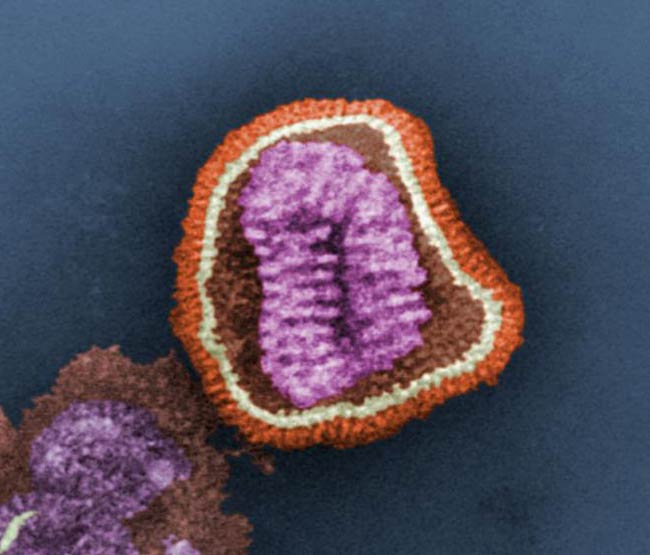

Viruses that cause the flu seem to spread best during the winter, and new research shows a tough, rubbery coat may be to blame. On the infectious agent, that is, and not on you.

Winter's cold and dry air has been shown to keep the flu airborne longer when a person coughs or sneezes, which helps explain why it's so prevalent these months. Now scientists think the pathogen's outer layer, normally liquid in warm conditions, hardens into a protective rubbery coat when chilled.

"Like an M&M in your mouth, the protective covering melts when it enters the respiratory tract," said Dr. Joshua Zimmerberg, a researcher at National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in Rockville, Md.

Zimmerberg and his colleagues detail their influenza findings in a recent issue of the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Melts in your mouth

Flu viruses can be smaller than 100 nanometers in size – tinier than particles found in smoke – and hitch rides in water droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

If the weather is warmer than 60 degrees F (16 degrees C), the virus' fatty, protein-studded coating stays melted while it travels through the air, weakening it and exposing it to drying out.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But cold weather, the study shows, gels up the liquid shield and increases the flu's chances of survival. Body heat melts the toughened viral coat when breathed in.

"It's only in this liquid phase that the virus is capable of entering a cell to infect it," Zimmerberg said, who imaged flu viruses both melted and gelled up with a technique called magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance.

New flu weapons?

Now that a crucial piece to the puzzle of the flu's winter-boosted virulence, or ability to infect, has been found, scientists are now searching for ways to turn the knowledge against the disease.

"The study results open new avenues of research for thwarting winter flu outbreaks," said Duane Alexander, director for the NICHD. "Now that we understand how the flu virus protects itself so that it can spread from person to person, we can work on ways to interfere with that protective mechanism."

During cold spells, the flu virus' hardened shield shell can be resistant to some detergents, so researchers plan to look for better soaps and hand-washing methods to combat it.

Until these and other techniques of fighting the flu are discovered, Zimmerberg thinks it may be wise to stay inside as much as possible when a severe form of the flu is on the loose, as the warm air helps melt away its defenses.

- VIDEO: Bird Flu Pandemic! Will it Happen?

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus