What's Happening Under Gibraltar?

The ground beneath Portugal, Spain and northern Morocco shook violently on Nov. 1, 1755, during what came to be known as the Great Lisbon Earthquake. With an estimated magnitude of 8.5 to 9.0, the temblor nearly destroyed the city of Lisbon and its lavish palaces, libraries and cathedrals. What wasn't leveled by the quake was mostly demolished in the ensuing tsunami and fires that raged for days. Altogether, at least 40,000 people were killed.

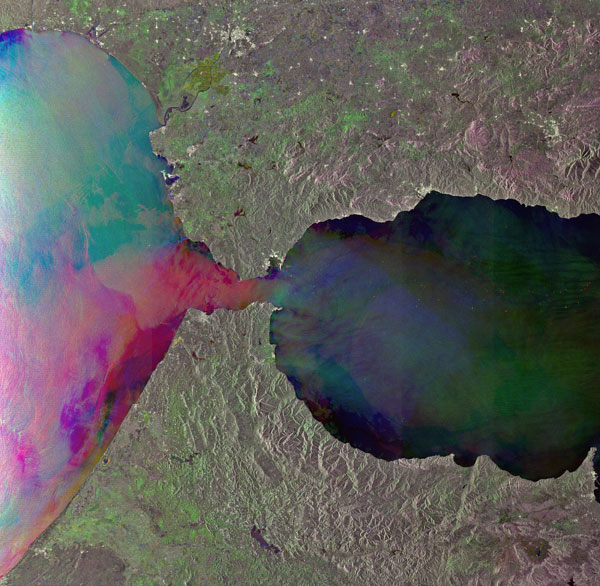

More than 250 years later, geologists are still piecing together the tectonic story behind that powerful earthquake. A unique subduction zone beneath Gibraltar, the southernmost tip of the Iberian Peninsula, now seems to be culprit. Subduction zones are the spots where one of Earth's tectonic plates dives beneath another, often producing some of the world's strongest earthquakes.

"At a global scale, subduction is the only process that produces magnitude-8 or -9 earthquakes," said Marc-Andre Gutscher, a geologist at the University of Brest in France. "If subduction occurred, and is still occurring here, then it's highly relevant to understanding the region's seismic hazards."

Small but powerful

Gutscher's work, discussed in the March 27 issue of the journal Eos, has shown that sunken ocean lithosphere — a layer that comprises Earth's crust and upper mantle — lies beneath Gibraltar, and that it's still attached to the northern part of the African Plate. Other teams have found crumpled ocean crust and active mud volcanoes in the Gulf of Cadiz, where water within the buried lithosphere mixes with sediments and boils up to the surface.

Altogether, these lines of evidence make a pretty convincing case for subduction, Gutscher said.

But unlike the textbook examples of huge subduction zones found at the Mariana Trench or under Alaska's Aleutian Islands, this subduction zone is comparatively tiny.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Its very small size and ultra-slow motion make the Gibraltar subduction zone unique," Gutscher told OurAmazingPlanet. "It's probably the narrowest subduction zone in the world — about 200 kilometers [120 miles] wide at most — and it's moving at far less than a centimeter per year."

What's happening under Gibraltar is an example of something called rollback subduction: As the sliver of lithosphere sinks into the mantle, the line where it's still "hinged" to the African Plate rolls back further and further, stretching the crust above it.

Seismic danger zone?

If subduction under Gibraltar is a thing of the past, there's little danger of future earthquakes. But that's not true if it is still happening — as Gutscher and many others believe to be the case.

That's because subduction has already created a tiny tectonic block, or microplate, between the African and Eurasian Plates. Researchers using GPS have shown that this microplate is still moving a few millimeters westward every year, thanks to ongoing rollback subduction.

The boundaries of this microplate lie in southern Spain and northern Morocco. Like California's San Andreas Fault, they're strike-slip boundaries (but smaller and slower-moving), so they're capable of generating earthquakes every now and then, Gutscher said. For example, a magnitude-6.3 quake struck the city of Al Hoceima, Morocco, in February 2004, killing nearly 600 people.

But as far as another Great Lisbon Earthquake, residents of this region can breathe easy — at least for another millennium or so. [10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"Given the very slow motion of the faults in the area, you need many centuries to build up enough slip to generate such a great earthquake," Gutscher explained. "A magnitude-8.5 or -9 earthquake is probably pretty much out of the question, since the last such tremendous event was only 250 years ago."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.