Underwater Nursery Tends Endangered Corals

The marine residents of hard-hit coral reefs near Puerto Rico may have noticed a sudden influx of strangers, thanks to a coral relocation and repopulation project that recently completed its most ambitious transplant to date.

Over two weeks in January, teams of divers installed more than 1,200 adult staghorn corals at various reef sites off Tallaboa, along Puerto Rico's southern coastline, in an effort to revive crucial ecosystems that suffered steep declines in recent decades.

The transplanted staghorn came from a local coral nursery that rose out of ecological disaster.

Salty silver lining

In April 2006, a 750-foot-long (228 meters) tanker ran aground on the Tallaboa reef, smashing about 2 acres of coral.

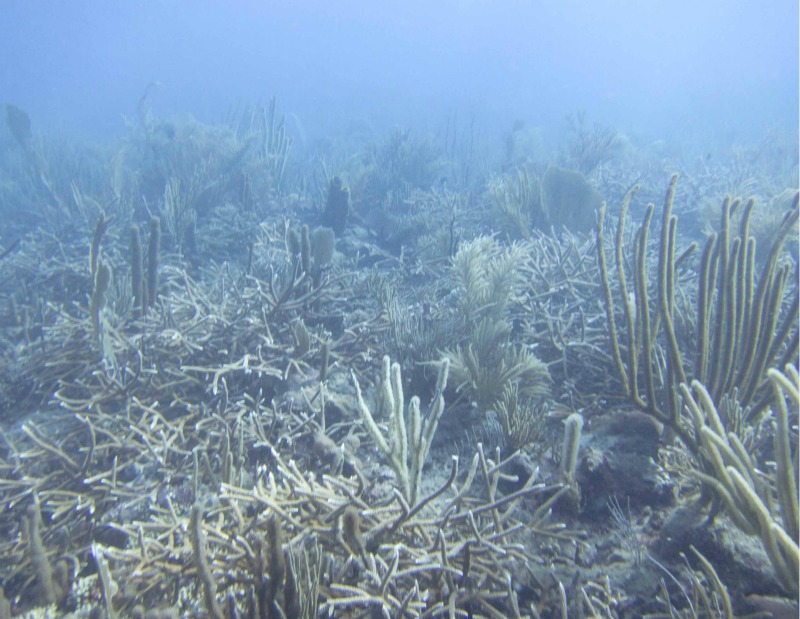

Such collisions wreak havoc on reefs' delicate topography. "After it's run over by a tanker, it [a coral reef] looks like a parking lot," said Sean Griffin, a habitat restoration specialist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and I.M. Systems Group, an environmental consulting firm.

Immediately after the tanker accident, divers salvaged pieces of the smashed coral and started up the nursery with just 100 small fragments of coral. Griffin, head of the coral nursery, said the team discovered through experimentation that line nurseries — which vaguely resemble coral vineyards — were the most successful. The nursery now keeps a population of 1,500 individual corals. [See images of the thriving coral nursery.]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Staghorn coral, a key reef-building species with unruly branches that can reach 6.5 feet (2 m) long, once ruled the balmy, subtropical waters around North, Central and South America. Over the last three decades, ship strikes have taken a toll, but less obvious killers such as disease and catastrophic bleaching events triggered by extreme temperatures really devastated the species.

In some places, staghorn coral populations have declined by 98 percent, and in 2006, staghorn and its cousin, elkhorn coral, were listed as "threatened" species under the Endangered Species Act.

Coral keepers

To raise the endangered coral, researchers tether small pieces of coral to rubber-coated wires that run above the seafloor. "They grow really quickly," Griffin said. To increase the nursery's population, researchers will simply "frag," or break off, pieces of the growing coral.

Suspended in the open water, the coral are lifted beyond the reach of hungry snails and predatory fireworms, and, in contrast to their anchored brethren, "you have three-dimensional growth, so it's almost doubling production," Griffin told OurAmazingPlanet.

Over two weeks in January, Griffin and a crew of divers moved 100 nursery-raised corals per day to sites as close as just 100 feet (30 m) from the nursery and, in other cases, transported the coral by boat to sites several miles away.

At the repopulation sites, crews used a variety of methods to replant the corals, attaching them to their new homes with cement, epoxy, carpentry nails or tie line, and sometimes simply wedging the corals into cracks in a reef.

"As long as they're stable and don't get loosened up and moved by the waves, they do fine," Griffin said.

The January coral "out-plant" was the largest yet in the region, and Griffin said he aims to repeat the process with staghorn coral every year. The next challenge, he said, is to increase the diversity at the nursery.

"We're trying to branch out into more corals," he said.

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.