Powerful Sun Storms May Sweep Away Space Junk

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Violent sun storms that shoot bursts of energy in Earth's direction have the potential to damage satellites and power infrastructures, but they can also clear the skies of dangerous space debris, NASA scientists say.

The energy from these intense solar eruptions, called coronal mass ejections, causes the atmosphere to expand, creating more friction on pieces of space junk in orbit. The resulting drag sends orbital debris plummeting back toward Earth faster than trash from previous years.

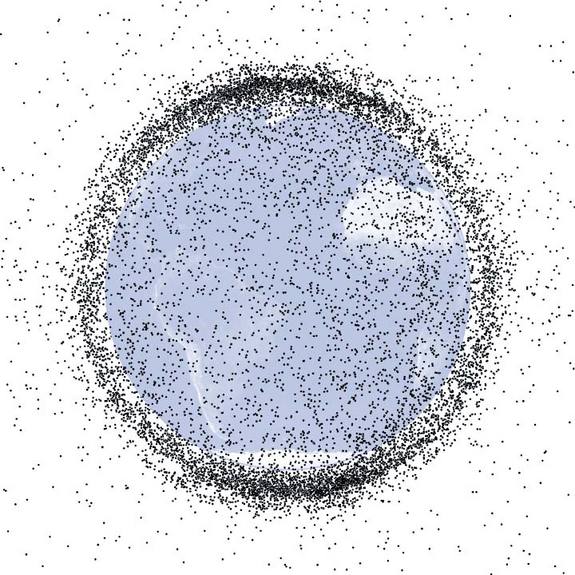

More than 22,000 pieces of spent rocket parts and pieces of hardware ripped off from satellite collisions and explosions circle Earth, a minefield for functioning satellites and space travelers. Over time, the pieces fall back toward the planet, often burning up in the atmosphere.

"Everything is falling down," Nick Johnson, chief scientist for NASA's Orbital Debris Program in Houston, told SPACE.com. "It's just a question of at what rate." [Photos: Space Debris & Cleanup Concepts]

Such a drag

As space trash interacts with Earth's atmosphere, resistance slows them, causing the debris to fall inward. But during periods of escalated solar activity, such as increases in sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections, the sun dumps more energy into Earth's atmosphere.

"When the sun is more active, it ejects more energy in the direction of Earth," Johnson said. "That energy is absorbed by the thermosphere, the upper part of the atmosphere."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Heat causes gases in the air to expand, and the thermosphere puffs out into space. More particles feel the resulting friction, and fall back toward the planet, mostly burning up in the atmosphere.

Earth's thermosphere is also constantly changing. In 2008 and 2009, while the sun was quiet, the upper atmosphere suffered a record collapse, contracting more than it had in almost half a decade.

The uptick in solar activity that began last year has caused the upper atmosphere to swell back up again, but it shifts in size on a daily basis.

This is because it depends on how often energy from the sun is aimed directly toward Earth, and that makes the thermosphere's expansion and contraction impossible to predict.

Eyes on the skies

The U.S. Department of Defense keeps track of more than 22,000 large pieces of space junk, Johnson said, producing daily updates that enable them to monitor individual items. They can keep tabs on the debris from individual satellites, such as the Chinese Fengyun-1C weather satellite, which China intentionally destroyed in 2007 with an anti-satellite device.

In NASA's latest edition of its Orbital Debris Quarterly News, which provides updates on space junk issues, Johnson noted that about half of the pieces of monitored space trash from the Chinese weather satellite that re-entered the atmosphere crashed back to Earth in 2011. A collision between an American and a Russian communications satellite in 2009 added a great deal of smaller space trash to the mix.

The atmosphere's effect on the bits and pieces depends a great deal on their size and mass. Johnson compares it to the movement of air on Earth: "The wind will blow a leaf much father than it will blow a tennis ball."

Thus, smaller, lighter pieces should feel the effects of the drag more keenly than their larger counterparts.

This is good news, since NASA estimates that around half a million pieces of space debris between 1 and 10 centimeters circle the Earth, while smaller particles can exceed tens of millions.

But the sun's activity in 2013 may not be as productive at the cleanup effort as in previous years, scientists predicted.

"We think it will be the lowest solar maximum of the space age," Johnson said.

Still, the thermosphere will only continue to expand as the sun moves toward its 2013 solar maximum, and that could mean an early death for many of the fragments orbiting our planet, he added.

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus