Bones Could Yield Dodo DNA

A newly discovered dodo skeleton has raised hopes for extracting some of the legendary extinct bird’s DNA.

The dodo, a flightless bird related to pigeons and doves, once thrived on the small island of Mauritius, located off the coast of Africa to the east of Madagascar.

Dodos, Raphus cucullatus, stood about three feet tall and laid their eggs on the ground, which made them easy targets for predators such as rats and pigs introduced to the island by European explorers. Humans also destroyed the dodos' habitat. The dodo became extinct in the late 1600s, just 80 years after the arrival of explorers.

Fred the dodo

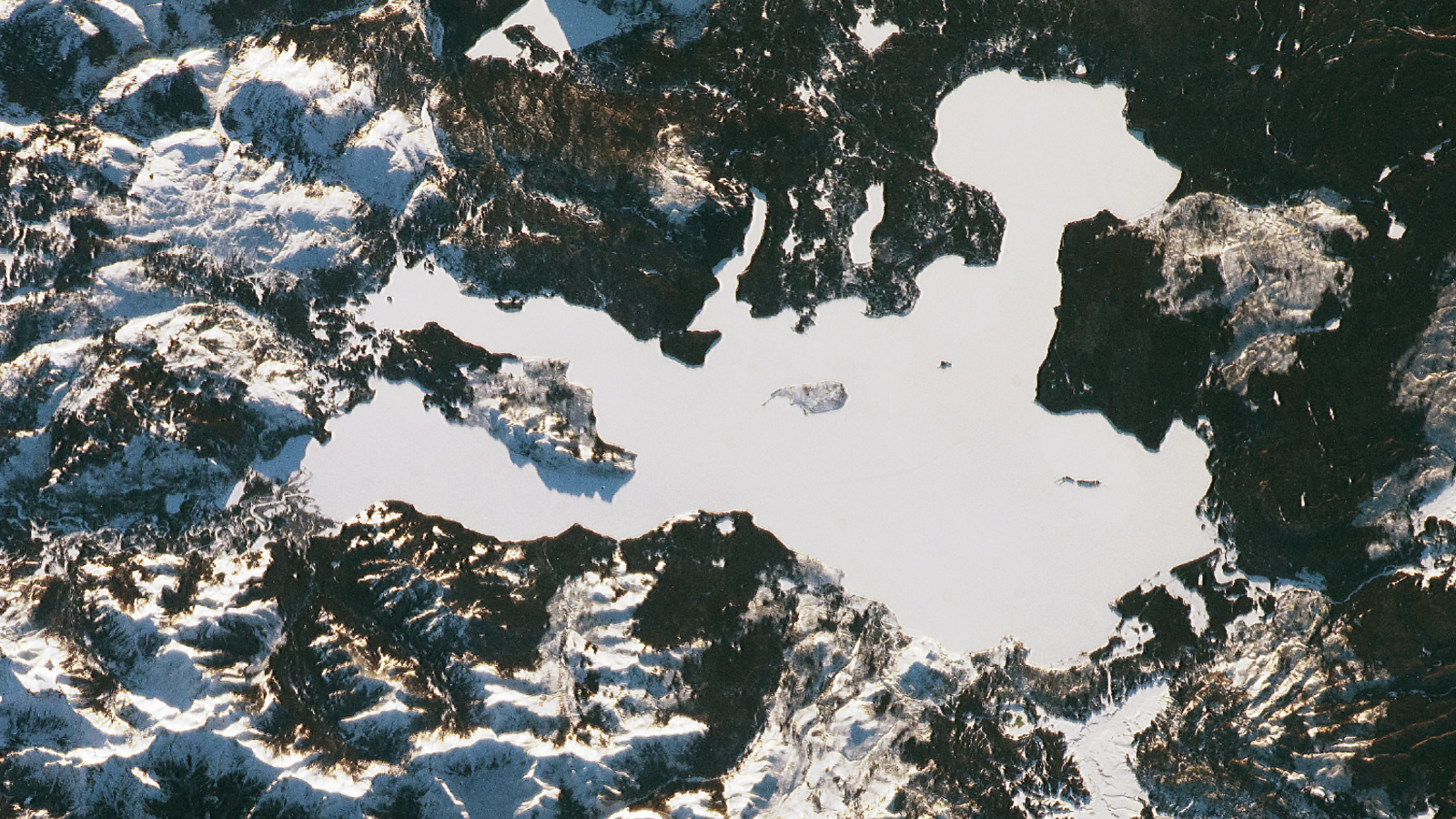

Late last year, biologists looking for cave cockroaches accidentally discovered a dodo skeleton in the highlands of Mauritius.

Nicknamed "Fred" after one of its discoverers, the skeleton's bones were badly decomposed and fragile, but there is still a good chance of extracting some dodo DNA because of the stable temperature and dry to slightly humid environment (keys to DNA preservation) of the cave.

(Scientists think Fred ended up in the bottom of the cave because he sought shelter from a violent cyclone but fell down in a deep hole and could not climb out.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dodo DNA would be of great scientific value because scientists know very little about the genetics of the dodo. Also, it would allow scientists to figure how long the skeleton was lying in the cave.

Mass marsh grave

Fred isn't the only chance for finding DNA of the extinct bird though, as dodo remains have been found before (but Fred's remains were the first found outside of coastal areas).

In 1865, a teacher named George Clark found numerous bones of dodos and other extinct animals in a coastal marsh called Mare aux Songes on Mauritius.

A team of researchers excavated the same marsh in 2005 and 2006 and found a bevy of dodo bones, including rare items such as a dodo beak and dodo chicks. This mass grave of dodos is thought to be at least 2,000 years old.

The find was deemed "of huge importance" by zoologist Julian Hume of the Natural History Museum in London in a 2005 press release announcing the discovery.

"[It] will give us a new understanding of how dodos lived," he said, including clues about how many dodos lived on the island, what they ate, how they bred and what their parenting style was before man showed up.

Unlike Fred's remains, the mass grave bones were well preserved, but no DNA has been successfully collected from them yet.

- Video: Extraordinary Birds

- Bird Extinctions More Rapid Than Thought

- Images: Rare and Exotic Birds

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.