Fossil Fragment Reveals Giant, Toothy Pterosaur

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

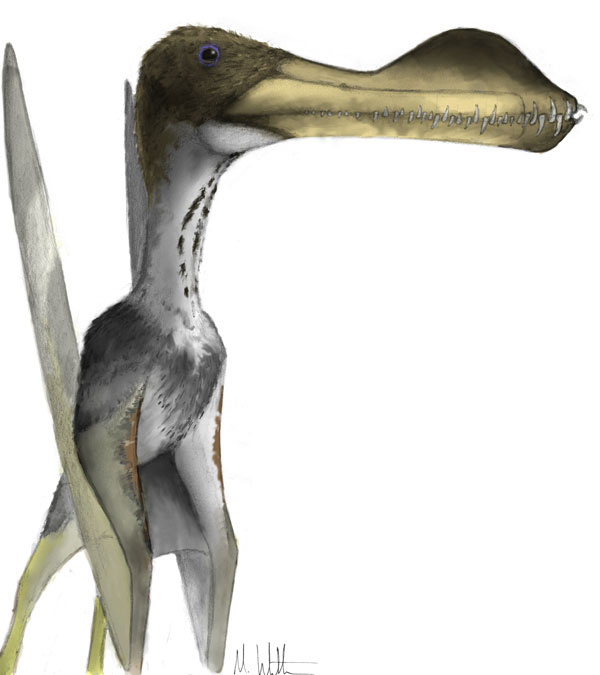

An examination of a small fossil — the tip of a toothed pterosaur's snout and a bit of its tooth — has revealed that a group of the extinct, flying reptiles could reach sizes larger than previously thought.

"What this research shows is that some toothed pterosaurs reached truly spectacular sizes and, for now, it allows us to put a likely upper limit on that size —around 7 meters (23 feet) in wingspan," said David Unwin from the University of Leicester, one of the researchers to examine the fossil, which has been in the Natural History Museum of London's collection since 1884. [Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils]

Pterosaurs are flying reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs, between 210 million and 65 million years ago. This fossil is believed to belong to a species of ornithocheirid, a type of fish-feeding reptile that was the largest of the toothed pterosaurs. It used the teeth on the tips of its jaws to grab prey while flying low over the surface of the water. Other types of pterosaurs, such as those without teeth, could reach much larger sizes, with wingspans of up to 33 feet (10 meters).

Article continues belowFrom the tiny fossil — which included the snout tip and a small bit of a tooth — the researchers were able to calculate the size of the animal.

"It's an ugly-looking specimen, but with a bit of skill, you can work out just exactly what it was. All we have is the tip of the upper jaws —bones called the premaxillae, and a broken tooth preserved in one socket," said David Martill, from the University of Portsmouth, who collaborated with Unwin. "Although the crown of the tooth has broken off, its diameter is 13 millimeters (0.5 inches). This is huge for a pterosaur. Once you do the calculations, you realize that the scrap in your hand is a very exciting discovery."

Based on the shape of the fossil fragment, they identified it as belonging to a species known as Coloborhynchus capito, a rare ornithocheirid. The fossil was collected in the mid-19th century from a deposit known as Cambridge Greensand in Cambridgeshire, England.

It's not clear why toothless pterosaurs could reach much greater sizes than toothed pterosaurs, but it may be because teeth are heavy, according to the researchers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study is published online in the journal Cretaceous Research.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus