Pterosaurs: Soaring Fliers and Light Landers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

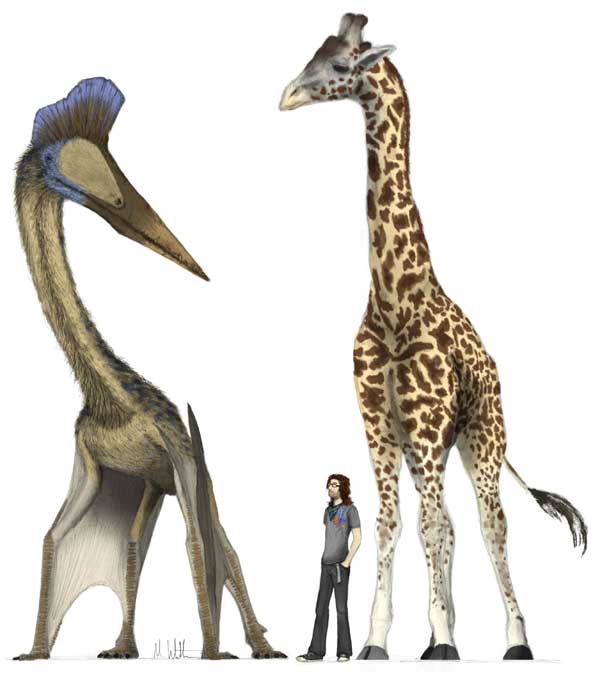

The largest flying animals ever known, the ancient pterosaurs, were light, fragile creatures best suited for catching rising air to soar, rather than braving strong winds, and for flying and landing slowly, according to new data from a doctoral student's wind tunnel tests.

"I wanted to understand how these animals flew, and as an engineer one of the first things you do is you measure the performance of the wing, and I realized no one had ever done that before," said Colin Palmer, a former engineer now studying paleontology at England's University of Bristol. His work is published in Wednesday's issue (Nov. 24) of the journal the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Pterosaurs had wings composed of a flexible membrane reinforced with fibers, and wingspans of up to 33 feet (10 meters). Palmer, who was once involved in yacht design, said a pterosaur wing has the aerodynamic characteristics of the mainsail of a sailboat, with the equivalent of a ring finger forming the leading edge of much of the wing, but with no additional support for the membranous wing other than its attachment at the ankle.

As an engineer, Palmer worked with wind turbines and electricity generation. He told LiveScience he came to paleontology with an interest in pterosaurs and flight.

Although scientists know from fossils that the wing was composed of a membrane, details were missing from the complete picture of wing anatomy, such as how far back the membrane extended behind the wing bone, Palmer said. It is also not clear how much the wings curved in the plane parallel to the body, an aerodynamic property called camber.

Palmer tested a series of simplified cross-sections simulating possible shapes for the wing in a wind tunnel, a research tool used to study the movement of air as it passes around objects. The resulting data indicated that pterosaurs experienced more drag than anticipated, and confirmed the previous theory that they were slow fliers.

"In order to fly at their best, they had to have quite a lot of camber in their wing membrane," Palmer said. "This means they fly at their best when they fly slowly."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This, in turn, indicates that they were best suited for calm tropical air, riding rising columns of air over coastlines and elsewhere. Their fragile anatomy — their hollow bones had a wall thickness of .04 inches (1 millimeter) — would have required low-speed landings, which the pterosaurs could have accomplished by altering the camber of their wing membranes to slow themselves as they descended, according to Palmer.

While pterosaurs came in many species and in many sizes, down to that of a blackbird, Palmer geared his tests for a generic pterosaur with a wingspan of about 6 meters (19.7 feet).

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus