What Is Fueling Hurricane Irene's Fury?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

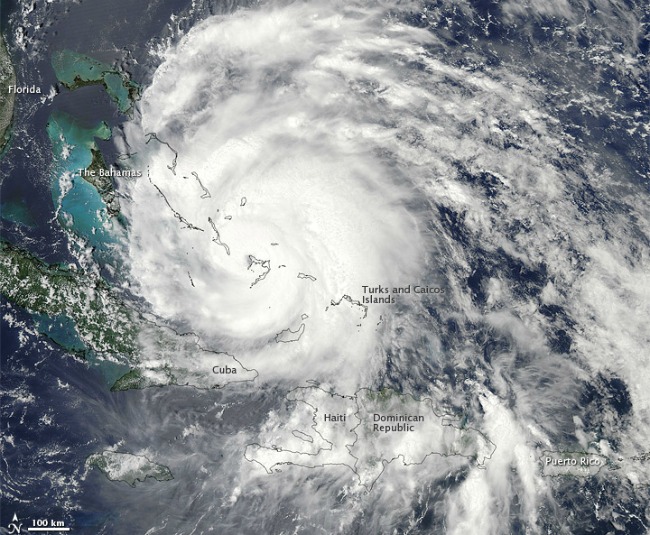

Hurricane Irene, the first hurricane of the 2011 Atlantic season, has now organized itself into a major storm and is barreling northward toward the United States' eastern coastline.

Although the storm is now centered over the Bahamas, hurricane watches are in effect along the North Carolina coast.

The hurricane is on track to affect large swaths of the Eastern Seaboard, and as far north as New York City public officials are warning of possible evacuations. [Related: Which US Cities Are Most Vulnerable to Hurricanes?]

Warm water, weak wind shear

Several factors have contributed to the growing strength of the storm, now a Category 3 hurricane packing winds of 115 mph (185 kph), which could intensify in the coming days.

"First and foremost, it has to be over warm waters," said Scott Braun, a research meteorologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "The key source of energy for the hurricane is the water vapor that's evaporated from the ocean surface."

Waters need to be around 79 degrees Fahrenheit (26 degrees Celsius) to fuel a hurricane, and Braun said ocean surface temperatures in the area where Irene formed and is now growing are around 84 F (29 C), "so it has sufficient energy."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition, hurricanes like peace and quiet to get organized, Braun said. The storms require low wind shear — meaning a low contrast between wind speeds at the surface of the ocean and higher up in the atmosphere. "And in this particular case the shear appears to have been quite weak," Braun said.

Weak wind shear appears to have played a major role when Hurricane Irene jumped from a Category 1 to a Category 3 storm yesterday (Aug. 24). [Hurricane Irene's Surge in Strength Caught on Video]

Hurricane Irene did weaken momentarily around Tuesday (Aug. 23), from a Category 2 to a Category 1 storm, but Braun said the change didn't represent a big shift in the storm's intensity.

"You can't read too much into that," Braun said. "Looking at the data, it went from 85-knot winds to 80-knot winds, so it was right at the threshold between the two categories." (85 knots is about 98 mph, or 157 kph.)

East Coast impacts

Irene has also been helped by the fact that it has been traveling over ocean water and small Caribbean islands, which are unlikely to hamper its strength.

When hurricanes move over land, they are deprived of their main energy source — warm ocean water. In addition, "you also have increased friction over land," Braun said, and topographical features such as mountains can disrupt the storm's circulation.

However, until the storm hits land — and it's not clear when and where this will happen — conditions that stoke intensification are readily available.

Warm water temperatures of roughly 84 degrees (29 C) extend as far north as North Carolina's outer banks, Braun said, providing the storm with ample fuel as it tracks up the East Coast.

Hurricane-hunting aircraft have been flying into the storm since Saturday (Aug. 20). The latest update from the planes indicates the storm has recently turned north-northwest as expected, and forecasters have shifted the projected track of the storm slightly westward, closer to the U.S. coastline.

"Significant impacts are likely along the United States East Coast regardless of the exact track it takes," according to the latest report from the National Hurricane Center.

"It's still moving over ocean temperatures that can more than support a Category 4 storm," Braun said, "and as long as the wind shear stays favorable, there's not really much to stop it from getting up to a 4."

Category 4 storms are those with wind speeds between 131 and 155 mph (210 and 249 kph).

Editor's Note: This story has been altered to reflect the following changes: Ocean waters begin to cool closer to North Carolina than Delaware/Maryland. In addition, hurricanes require water temperatures of just 79 degrees Fahrenheit (26 degrees C) for fuel, not 82 degrees.

Andrea Mustain is a staff writer for OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to Live Science. Reach her at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus