Climate Fluctuations May Increase Civil Violence

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Global climate fluctuations bear some responsibility in violent conflicts, according to a new study that has linked the hot, drier weather brought by the El Niño climate pattern with civic conflicts within the affected countries.

Using data from 1950 to 2004, the researchers concluded that the likelihood of new conflicts arising in affected countries, mostly located in the tropics, doubles during El Niño years as compared with wetter, cooler years. The weather El Niño brings had a hand in roughly one out of five conflicts during this period, they calculate.

"We believe this finding represents the first major evidence that global climate is a major factor in organized violence around the world," said Solomon Hsiang, the lead author of the study who conducted the research while at Columbia University. [10 Ways Weather Changed History]

This conclusion — that fluctuations in climate can contribute to violence in modern societies — is a controversial proposal. In this case, the researchers admit they have yet to untangle the mechanisms that link a change in sea surface temperature with, for example, a guerilla war.

A natural climate fluctuation

El Niño refers to the irregular warming of the surface of the Pacific Ocean near the equator. This alters the behavior of the ocean and the atmosphere, disrupting weather around the planet — normally wet regions dry out, and dry regions become wet. El Niño happens roughly every four years, though it is not completely predictable, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

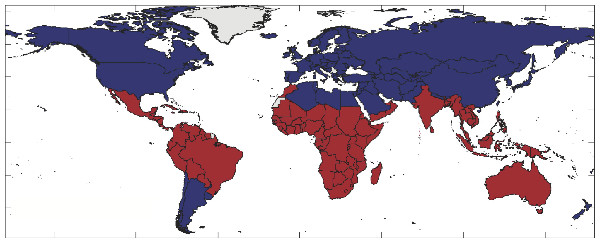

The study focused on areas, primarily in the tropics, where El Niño brings hot, dry weather to land, as more rain falls over the ocean.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hsiang and colleagues looked at civil conflicts — in which more than 25 battle-related deaths occurred in a new dispute between a government and another, politically incompatible organization — in El Niño and other years.

Among nations that are strongly affected by El Niño, they calculated that the annual risk of conflict rose between 3 percent and 6 percent during an El Niño event. By modeling a world in a perpetually moist, peaceful state (no El Niño), they found that 21 percent fewer conflicts occurred during the 54-year-period. This doesn't mean that the climate cycle caused one in five conflicts, rather that it contributed to one in five, according to the researchers.

But not all countries warmed by El Niño responded the same way.

"We find it is really the poorest countries that respond to El Niño with violence," said Hsiang, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton University. "There are a large number of relatively wealthy countries in the tropics, for example, Australia, that experience large climate fluctuations due to El Niño, but they do not lapse into violence."

Ice on the road

The researchers admit that they have yet to explain how unusually warm sea surface temperatures are connected with violence. El Niño can clearly lead to droughts and natural disasters such as floods and hurricanes, but connecting those effects through to human behavior becomes tricky.

There are theories: El Niño-influenced events can put a strain on societies, particularly on the poor, leading to income inequality and increased unemployment, which may make armed conflict more attractive, according to the researchers. Psychological factors may also contribute.

"When people get warm and uncomfortable, they get irritated. They are more prone to fight, more prone to behave in ways that are, let's say, less civil," said Mark Cane, a study researcher with the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University. "I think all of these things contribute, and they are all quite real."

Hsiang compared El Niño's role in violence to that of winter ice on a road in a car accident: The ice alone doesn’t cause the accident, but it contributes to it.

An earlier, controversial study lead by economist Marshall Burke linked civil war in sub-Saharan Africa with warmer-than-average temperatures.

Why do we fight?

Although we frequently engage in it, we still don't fully understand the causes of violent conflict, according to Halvard Buhaug, a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, who was not involved in the current study. [The Evolution of Fighting]

No conflict has a single cause, and researchers have come quite far in identifying a few common factors — poverty, inequality, political exclusion of minority groups and political instability — that can lead to civil violence, Buhaug said.

"From the recent study, one would be tempted to add climate or climate cycles. I think that would be premature," he said.

While it's possible that changes in climate brought down ancient civilizations — the collapse of ancient Egypt, the Mayan Empire and others have been linked to extreme climate fluctuations — Buhaug is less open to the same causal link for the modern world.

While Hsiang and colleagues show that El Niño and violent conflict tend to coincide, they do not provide the evidence that one can cause the other, he said. In order to establish a causal relationship, the researchers need to look at individual cases, and trace out precisely how an unusual climactic event, like El Niño, led to a specific conflict.

"Until we are able to do that, I don't think we are in a position to claim there is a causal relationship between climate and conflict," Buhaug told LiveScience.

Though scientists have yet to study that causal relationship in modern times, researchers have shown how environmental stress plays a role in violence — for instance, the influence of a drought in the Rwandan genocide, said Thomas Homer-Dixon, a professor at the University of Waterloo and chair of global systems at the Basillie School of International Affairs. Climate change is expected to behave like some other environmental stresses, said Homer-Dixon, who wasn't involved in the current research.

"This story is becoming clearer, it is not really told yet," he said. "[The current study] is a very important contribution to that overall story."

The future

If a natural climate cycle is contributing to violent conflict, what can we expect from climate change caused by humans, who are pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere?

The study itself doesn't address human-caused climate change, but its findings do have implications, according to Cane.

"It does raise the reasonable question: If these smaller, shorter lasting and by-and-large less serious kinds of changes in association with El Niño have this effect, it seems hard to imagine the more pervasive changes that will come with anthropocentric climate change are not going to have negative effects on civil conflict," Cane said.

The research appears in the Aug. 25 issue of the journal Nature. Kyle Meng, of Columbia University, also contributed to the study.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus