'Lost' Rainbow Toad Rediscovered After 87 Years

After months of scouring remote forests in Borneo, researchers spotted three rainbow toads up a tree, snapping the first-ever photographs of this elusive amphibian species that hadn't been seen for 87 years, scientists announced today (July 13).

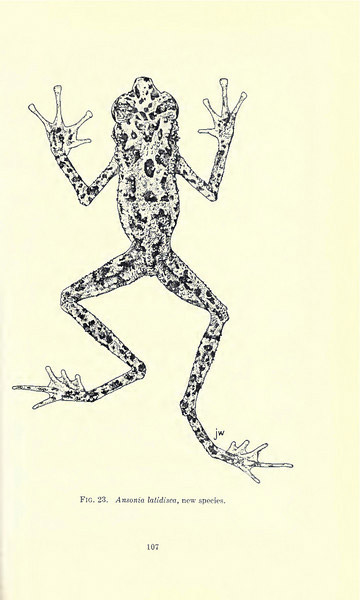

Last seen in 1924, the Bornean rainbow toad (Ansonia latidisca) had been listed as one of the world's top 10 most wanted lost frogs, or those that hadn't been seen in at least a decade. Conservation scientists thought the chances of spotting the spindly-legged toad were slim.

In fact, until this rediscovery, scientists had only seen illustrations of the mysterious and long-legged toad existed, after collection by European explorers in the 1920s. [See images of lost rainbow toad]

"When I saw an email with the subject 'Ansonia latidisca found' pop into my inbox I could barely believe my eyes," said Robin Moore of Conservation International, adding that an attached image proved the unbelievable finding. "The species was transformed in my mind from a black and white illustration to a living, colorful creature." (Moore launched the campaign the Global Search for Lost Amphibians.)

Three individuals of the missing toad, including an adult female, adult male and a juvenile, were documented up three different trees in Penrissen, a region outside the protected area system of Sarawak, which is one of two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo. The toads ranged in size from 1.2 inches (30 millimeters) for the juvenile to 2.0 inches (51 mm) for the adult female. All three sported long, skinny limbs and bright skin pigments. [Mug Shots: Top 10 Lost Amphibians]

Initial searches by Indraneil Das of Universiti Malaysia Sarawak and colleagues took place during evenings after dark along the high rugged ridges of the Gunung Penrissen range of Western Sarawak. The first few months proved fruitless; so the team decided to include higher elevations in their search. And one night last August on of Das' graduate students, Pui Yong Min, found one of the three gangly toads up a tree.

If you want to see newly rediscovered frog, however, it's probably best to look at the photos, as Das has said he won't divulge the exact site of the rediscovery right now, owing to the intense demand for brightly-colored amphibians by those involved in the pet trade.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The effort was part of the global search for lost amphibians by Conservation International, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Amphibian Specialist Group, with support from Global Wildlife Conservation. The large search involved 126 researchers who scoured areas in 21 countries, on five continents, between August and December 2010.

The hope was to determine whether the lost amphibians had survived increasing pressures, such as habitat loss, climate change and disease — a fungus that causes the infectious disease chytridomycosis is devastating amphibian populations worldwide.

The only other member of the Top 10 list that has been rediscovered is the spotted stubfoot toad (Atelopus balios), which is restricted to a very small area in southwestern Ecuador.

The rediscovered Borneo species is listed as Endangered by the IUCN's Red List.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.