Genetically Engineered Cell Shoots Out First-Ever Biological Laser

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that the cell is not bacterial as was stated in an earlier version.

Some cells fight disease. Other cells form hair and bone. And now, thanks to some fancy genetic engineering and a pair of tiny mirrors, a specially altered kidneycells shoot the first-ever biological laser beams. Admit it, that is cooler than forming hair.

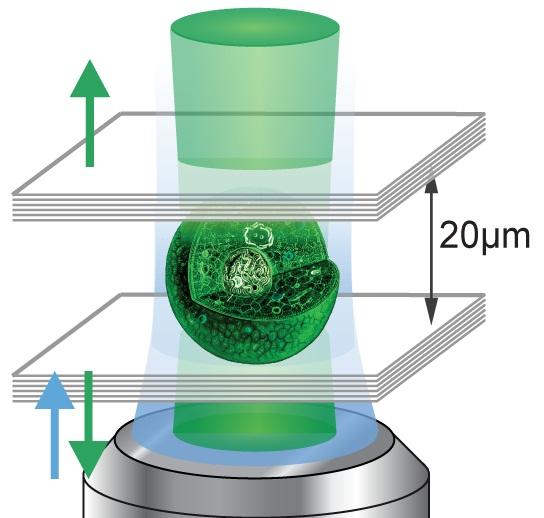

By harnessing the light-emitting power of green florescent protein (GFP), scientists working at Massachusetts General Hospital created the biological laser merely as a proof of concept. Aside from implying the future possibility of a self-healing laser that requires no battery, this breakthrough could allow doctors and scientists to view the inner workings of individual cells without a microscope.

"The initial motivation was really scientific curiosity," said Malte Gather, a physicist at Massachusetts General Hospital who co-created the laser cell. "When we started with the project, it was close to the 50th anniversary of the first demonstration of the laser. Everyone had looked at inanimate material, and we noticed that in nature, laser light does not occur. We wanted to know if there was a reason for that, if we could make a fully biological laser."

GFP protein acts as a copy machine of sorts, absorbing regular blue light and releasing identical particles of green light. Whereas regular light contains light particles in a range of different wavelength frequencies, laser beams contain only coherent light particles with the same profile. Since GFP always releases light particles with the same profile, the scientists simply needed to funnel the light into a single beam to create the biological laser, Gather told InnovationNewsDaily.

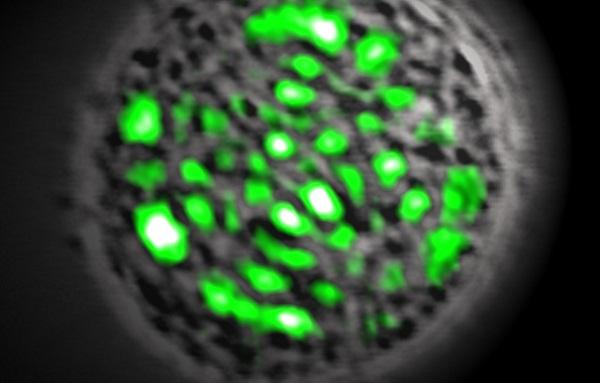

As expected, the laser emitted by Gather′s cells lacks the power of commercial lasers, limiting immediate practical uses. However, since the internal components of the cell shapes the laser beam, this technology could provide researchers with a tool for producing detailed images of microorganisms without using a microscope.

"You wouldn't use a living laser to replace a high-powered industrial laser to cut steel. But there are some applications in the medical field since the pattern of the light beam reveals the shapes and the structures inside the cell. It isn't just a circular dot like a laser pointer — it's a very complex pattern," Gather said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moving forward with the research, Gather and his colleague Seok Hyun Yun plan on figuring out how to put the mirrors inside the cell itself, and then engineering the cell so it generates its own blue light for later conversion into the green laser.

Once a cell can contain and internally produce all the components needed to make a laser, a whole new field of biological laser use opens up.

"One neat application of a living laser beam is that, GFP, like most laser materials, degrades over time. But the fact that the cell is alive means that the laser can self-heal," Gather said. "Lasers have the notorious quality of just dying sometimes. If the GFP gets degradeds, the cells can just make more of it. Very long term, this could be an interesting advantage to having a living cell producing laser light."

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.