DNA for Dinner: Strange Microbial Menu Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

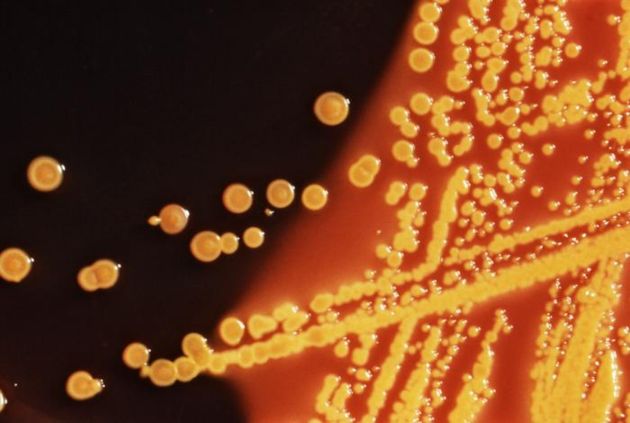

When Escherichia coli bacteria sit down at the dinner table, they often feast on the DNA of their dead competitors, a new study reports.

The E. coli bacteria live in the guts of warm-blooded animals, where they aid digestion. Some strains produce toxins that can kill people, however. They become dangerous when picked up from contaminated food.

The bacteria are hardy creatures. And those that can manage to live a little longer than their peers not only end up having less competition for food, but also can eat their long lost friends.

"The bacteria actually eat the DNA , and not only that, they can use the DNA as their sole source of nutrition," said Steven Finkel, assistant professor of molecular and computational biology at the University of Southern California.

It makes sense that DNA is a food source for some microbes, the researchers say.

"You're surrounded by living things, and living things die," Finkel said. "Where does all that stuff go? Why aren't we up to our ears in DNA, in ribosomes, in plant protein?"

The study found eight genes in E. coli that allow it to consume DNA without causing any genetic harm to the bacteria.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The same gene family is found in many other species, suggesting that the use of DNA as a nutrient may be a widespread phenomenon, the researchers reported. Understanding how these genes work can have applications in medicine and make advances toward genetic antibiotics.

For example, researchers could turn off the quality in pathogens of patients with cystic fibrosis that makes it capable of feeding on the DNA in the lung tissue, Finkel explained.

The study is detailed in June 1 issue of the Journal of Bacteriology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus