Meet 'Mrs. T': Ancient Flying Reptile Found with Egg

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

As birdlike as the extinct winged reptiles known as pterosaurs might have seemed as they soared through prehistoric skies, it turns out their eggs and nests might have been like their more grounded lizard cousins than any feathered rival, scientists find.

These insights, based on the fossils of a female pterosaur named "Mrs. T" and her egg, shed light on bygone creatures that once ruled the skies for more than 150 million years, whose home life we are only beginning to understand.

Pterosaurs included the largest flying animals ever known. They dominated the air beginning 220 million years ago, until they went extinct at the end of the age of dinosaurs some 65 million years ago. (Although pterosaurs lived at the same time as dinosaurs, they were a separate group of reptiles, not dinosaurs.)

Until recently, there was scant fossil evidence as to what pterosaur young were like. With such little to go on, researchers often speculated that pterosaurs reproduced mostly like birds, picturing them nesting on eggs and caring for hatchlings until they could fly. [Which Came First? Eggs Before Chickens, Scientists Say]

Now scientists have discovered a female pterosaur preserved together with one of her eggs, shedding light on what the reproductive strategies of these reptiles might have been like. These new findings reveal that pterosaur eggs and nests may not have been birdlike after all.

Introducing Mrs. T

The pterosaur was a Darwinopterus, a specimen roughly 30 inches (78 centimeters) in wingspan and between 110 and 220 grams in weight that lived about 160 million years ago in what is now Liaoning province in China. Back then, the province would have been a semitropical, heavily forested area filled with dinosaurs, mammals, lizards, salamanders and fish amid lakes and volcanoes. The fossil was bought from a farmer who excavated it from rocks there.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

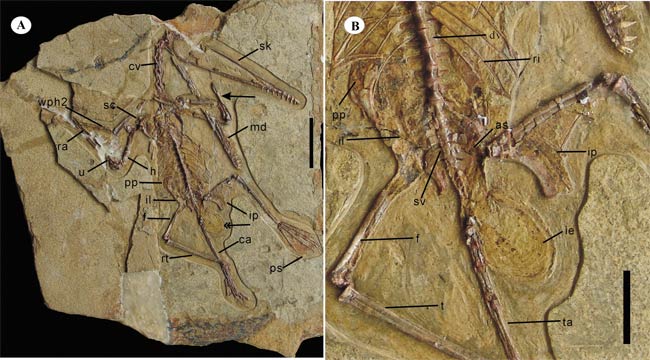

The nearly complete skeleton of this adult pterosaur was found with an egg, revealing the adult was a female. "We named her Mrs. T because she's a pterosaur," said researcher David Unwin, a paleobiologist at the University of Leicester in England. (The "p" in pterosaur is silent, meaning it sounds as if it begins with a "t.")

Mrs. T had a broken left forearm. This suggests that she had a violent accident that made her fall into the water and drown, with her body expelling the egg as she decayed, researchers said.

Pterosaur eggs have been found before, some holding intact embryos. However, they were never found together with pterosaurs, so there was no sure way of telling which of the 133 pterosaur species described to date that they belonged to.

"Actually finding any animal preserved with an egg or an embryo is extremely rare, and incredibly valuable from a scientific point of view," Unwin told LiveScience. "For instance, we would love to know what gender our fossils might be, but in 99.9 percent of the cases, we have no way of being certain otherwise."

The new discovery may change that, at least for pterosaurs. Mrs. T revealed that female pterosaurs had relatively large hips and unadorned skulls. On the other hand, males had extraordinary crests of bone on top of their skulls but relatively small hips, which makes sense, as they did not have to lay eggs. Similar variations have been seen in about 40 percent of all known pterosaur species.

"Now that we know that these spectacular crests were linked with sex, we can begin to explore what specific roles they might have played," Unwin said. "Maybe they were used to intimidate other males, or maybe females selected males with the biggest crests. In some pterosaur species, crests were five times the height of the skull — maybe they could've been an impediment to flying, and if they could cope with such a handicap, they could have shown they were the best to mate with."

Egg of a reptilian flyer, not a birdlike one

The egg, some 28 millimeters long, 20 millimeters wide and originally about 6 grams in weight, was relatively small compared with the pterosaur mom's body. It had a parchment-like shell that was probably soft, as no evidence was found of the calcium-rich layer seen in hard eggshells. [Image of fossil egg]

"If a hard shell was there, we would be pretty sure it'd be preserved with the rest of the fossil, and there were other shelled creatures there whose shells were still present, so there was no chemical process dissolving those hard shells away," Unwin said.

Nowadays, birds the size of this pterosaur would likely produce eggs up to nearly three times the size of this fossilized egg, since hard-shelled bird eggs must hold all the resources needed to sustain the developing embryo inside. Instead, this soft-shelled pterosaur egg could have soaked up water and nutrients from the ground.

Pterosaurs might have thus buried their eggs like other reptiles, with little need for care afterward. Indeed, the size of the egg relative to Mrs. T is comparable with what is seen in reptiles such as lizards and snakes, Unwin said. Also, "if the shells are soft, you can't sit on them — you'll squeeze them," he explained, squashing the embryos inside

Past research into pterosaur eggs also revealed that any newborns would be developed enough to fly within hours or days after hatching. "They would've been like tiny versions of adults, unlike what you see with most birds," Unwin said. "All in all, there would have been no need to care for eggs or young ones."

In many ways, these small soft eggs could have granted adult pterosaurs a much freer lifestyle than most birds have. Pterosaur mothers would have had to invest far fewer resources in their eggs than birds do, and parents could just leave their young behind to pursue their own lives.

Still, a number of reptiles do care for their young, either watching over their eggs or hatchlings to make sure predators don't get them.

"Pterosaurs might have cared for their young," Unwin said. "We could look for fossil trackways that preserved pterosaur footprints to see if there were any large ones with small ones, suggesting that adults were accompanied by little ones. We haven't found any such yet, but if we did, that certainly wouldn't upset us."

Unwin with Junchang Lü at the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences in Beijing and their colleagues detailed their findings in the Jan. 21 issue of the journal Science.

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Top 10 Beasts and Dragons: How Reality Made Myth

- Dinosaur Dads Watched Over Eggs

You can follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus