Scientists Generate Electricity in Novel Way

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers say they have successfully generated electricity from heat by trapping organic molecules between metal nanoparticles, a finding that could yield cheap refrigerators, not to mention new, more efficient energy sources in general.

Currently, about 90 percent of the world's electricity is generated by burning fossil fuels, which creates heat, often in the form of steam. The steam spins a turbine that drives a generator to produce electricity.

But this method is indirect, and in the process, plenty of heat is wasted and its energy goes uncaptured.

"Generating 1 watt of power requires about 3 watts of heat input and involves dumping into the environment the equivalent of about 2 watts of power in the form of heat," said lead author Arun Majumdar of the University of California at Berkeley.

For the past 50 years, scientists have been exploring ways to use this wasted heat.

"If even a fraction of the lost heat can be converted into electricity in a cost-effective manner," Majumdar said, "the impact it would have on energy can be enormous, amounting to massive savings of fuel and reductions in carbon dioxide emissions."

But the temperature at which that heat is released is too low to be used by traditional heat engines, so researchers have been developing thermoelectric converters to change the heat to electricity more directly.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The converters operate based on a phenomenon called the Seebeck effect: When the junctions of two metals are kept at different temperatures, they respond differently to the temperature difference, and a voltage is generated.

But such converters are far less efficient than traditional heat engines and rely on rare, expensive metals and so are impractical for widespread use.

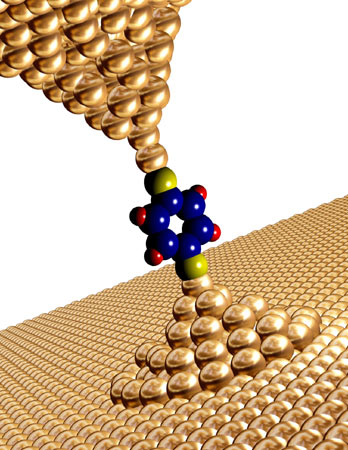

In the new study, Majumdar and his colleagues coated gold electrodes with three different organic molecules and were able to generate a voltage--the first time the Seebeck effect has been observed in organic molecules. Though the voltage was only seen across an individual molecule, the researchers will eventually work up to multiple junctions.

Widespread use of thermoelectric converters could be simpler and more efficient with organic materials because they are cheap, abundant and easily processed. (Though gold electrodes were used for this study, eventually iron or silicon electrodes will be used, according to the researchers.)

"The use of inexpensive organic molecules and metal nanoparticles offers the promise of low-cost, plastic-like power generators and refrigerators," Majumdar said.

The researchers caution that this is just the first step, but are optimistic about the technological potential.

"We are going down the road of cheap thermoelectric materials," said Majumdar's colleague Pramod Reddy. The research is detailed in the Feb. 15 issue of the online version of the journal Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus