River Blindness Parasite Relies on Bacteria to Fool Host

Even in the strange world of symbiosis, in which a pair of organisms can depend on each other to live, this one's a whopper: Bacteria living inside a parasitic worm help create a cloak, shielding the worm from the immune system of its hosts (which, in this case, turn out to be us).

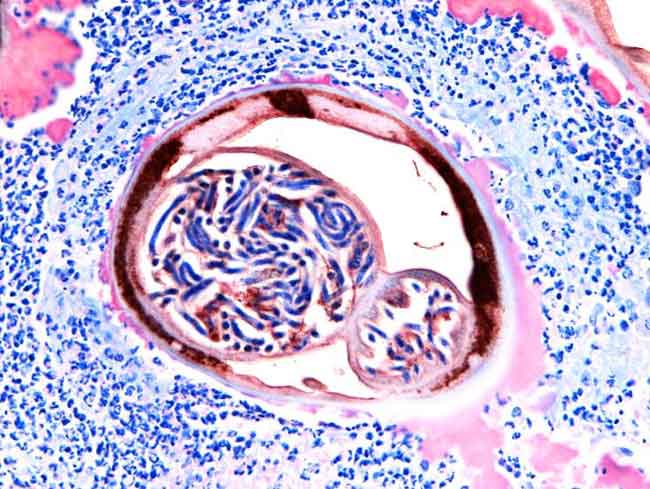

The worm in question is Onchocerca volvus, a parasitic nematode that causes river blindness. The worm is transmitted to humans by blackfly bites, and it has infected about 18 million people, most of them in Africa. It causes an itchy rash, nodules and, in some 270,000 cases, blindness.

"It's a worm containing another organism, so the body during this infection is kind of confused about what it is dealing with," Benjamin Makepeace of the University of Liverpool, who led research into the infection, told LiveScience. "It's very unusual; most parasites that infect people are a single organism."

Once this odd parasitic nematode infects someone, white blood cells called neutrophils that are part of that person's immune system detect the Wolbachia bacteria and surround the worm-bacteria complex. These neutrophils attack the bits of bacteria that linger outside the worm, but they are specialized and are unable to attack the worm itself. They also are unable to reach the bacteria on the inside. Instead they linger and essentially form a cloak around the worm, keeping away other white blood cells that would attack it.

"The body's immune response isn't seeing the proper target. It's being redirected to something else," said Makepeace.

A good model for studying this infection came from the closely related Onchocerca ochenai, which infects cattle. Makepeace treated infected cows with two different drugs. One killed the worms directly. The other, an antibiotic, killed the Wolbachia bacteria in the worms, which in turn led to the worms' death.

White blood cells called eosinophils, regarded by many scientists as just a clean-up crew once worms are already dead, failed to act after the worms in the cow were killed by the first drug. The presence of the neutrophils stopped them. However, when the antibiotic was used to kill the bacteria first, the number of neutrophils dropped and the eosinophils came in to attack the live worm.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The eosinophils are actively involved in killing but can only do that when the bacteria have been reduced in number and the neutrophils aren't there," Makepeace said.

Katrin Gentil, an Onchocerca researcher at the University of Bonn, in Germany, reacted to the research by saying, "The role of Wolbachia in immune-modulation has been neglected in the past. Makepeace's group has shown that Wolbachia have a beneficial role for the worm by modulating the host's (in this case cow's) immune response. This is an exciting novel finding."

Gentil, who made her remarks to LiveScience by e-mail, was not involved in the study.

Previous research found that the parasite can be killed with antibiotics, but treatment must be administered daily for six weeks.

Makepeace's team is hoping to make the antibacterial treatment shorter, easier and less expensive. The researchers are working to design a worm protein that could be administered after infection to "prime" the host's eosinophils to kill the worm.

Other worms in the Onchocerca family cause lymphatic filariasis in humans and infect other animals.

"The immune system is important in the mechanism of action of the antibiotics," Makepeace said.

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites

- Study: Cat Parasite Affects Human Culture

You can follow LiveScience Staff Writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus