Brain Cells That Help Us Breathe Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

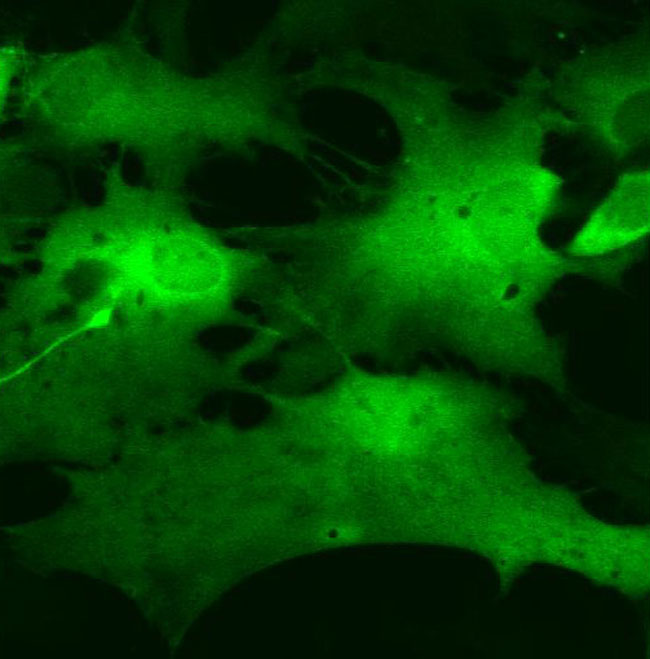

Star-shape brain cells previously thought to take a back seat in terms of the brain's activity might play a key role in controlling breathing, a new study in rats suggests.

When we breathe, we take in vital oxygen and expel waste carbon dioxide. The study results show brain cells known as astrocytes can sense changes in blood carbon dioxide levels and then signal other brain networks to adjust breathing.

"This research identifies brain astrocytes as previously unrecognized crucial elements of the brain circuits controlling fundamental bodily functions vital for life, such as breathing, and indicates that they are indeed the real stars of the brain," said study researcher Alexander Gourine of University College London.

It's possible that these brain cells or others like them contribute to disorders associated with respiratory failure such as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). However, more research is needed to prove the links, the researchers say. Also, while rats are considered a good model for studies on the human brain, future research is needed to make sure the results hold true for humans as well.

The study will be published this week in an early online edition of the journal Science.

The other brain cells

Astrocytes belong to a group of brain cells known as glial cells (glia is Greek for "glue"). Until recently, glial cells were thought to be minor players in the brain, providing structural and nutritional support to neurons, which did the heavy lifting.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's called neuroscience because it's neuro-centric," Gourine said. "Astrocytes and other glial cells, they were considered to not be as exciting to study previously."

However, Gourine and his colleagues found that astrocytes directly respond to decreases in blood carbon dioxide levels. Once activated, astrocytes send out a chemical messenger called ATP, which in turn stimulates other networks in the brain involved in respiration. Breathing in the study rats was increased when astrocytes indicated levels of carbon dioxide were too high, a reflex to get rid of the extra gas, and decreased when carbon dioxide levels were too low.

Role in disease?

While no one knows what causes SIDS, previous research has suggested abnormalities in the brain stem or an inappropriate response to low blood oxygen levels could play a role.

"This basic science information has to be used rapidly in order to determine whether glial dysfunction contributes to serious disorders of central control of breathing underlying Sudden Infant Death Syndrome." Gourine said. "If this hypothesis is correct astrocytes may be considered as potential targets for therapy in preventing respiratory failure".

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the British Heart Foundation.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus