Mine Disaster CSI: Earthquakes Shed New Light on Utah Collapse

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

One of Utah's deadliest mine disasters may have brought down the entire Crandall Canyon coal mine, according to a new seismic study presented today (April 19) at the Seismological Society of America's annual meeting in Salt Lake City.

At Crandall Canyon, a room carved from coal collapsed 1,500 feet (457 meters) below the surface on Aug. 6, 2007, trapping six workers. A tunnel collapse on Aug. 16 killed three rescuers digging toward the suspected location of the miners. The bodies of the six miners were never recovered.

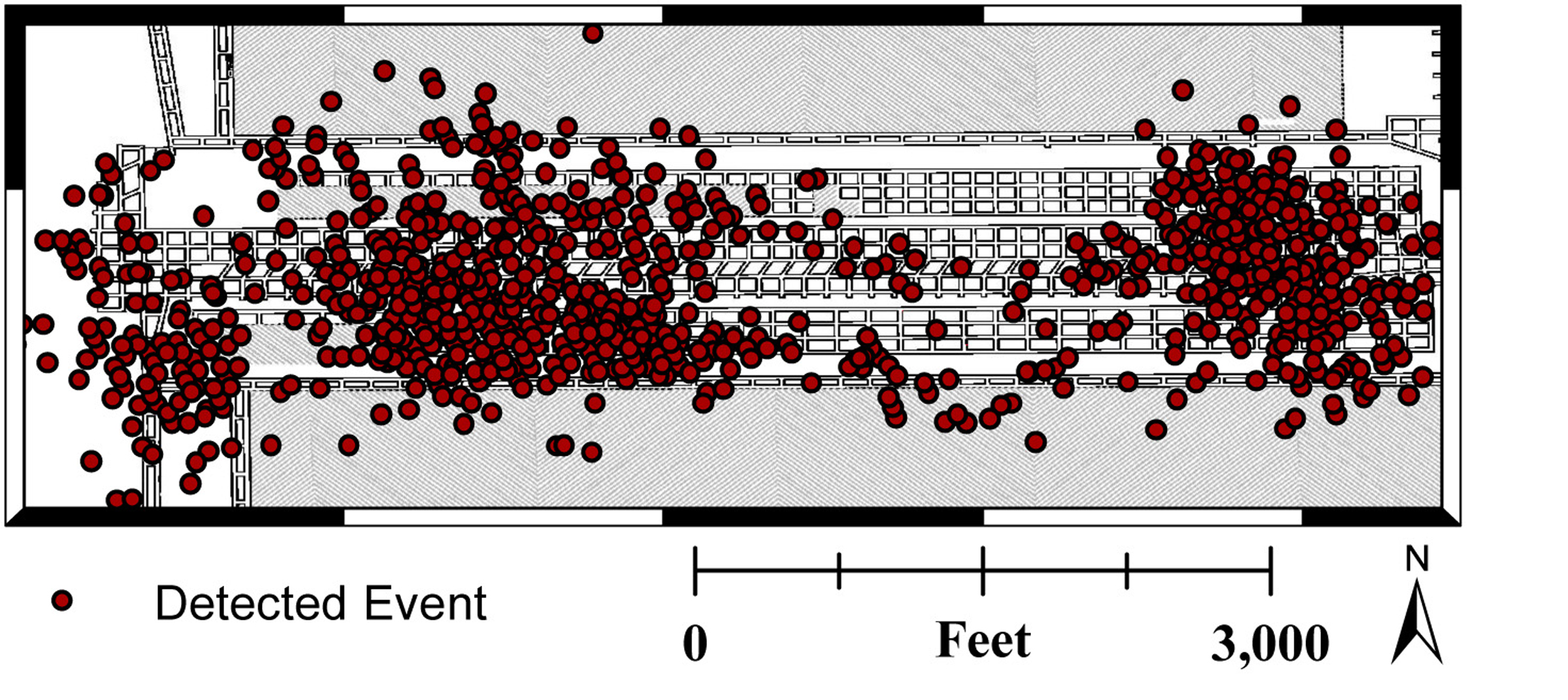

With new analysis techniques, researchers at the University of Utah identified up to 2,000 tiny, previously unrecognized earthquakes before, during and after the coal mine collapse.

The tremors would register magnitude minus -1, with energy equivalent to a small hand grenade, said Tex Kubacki, a University of Utah master's student and study co-author. "They could be from rocks falling, from roof faulting — anything that produces a vibration," he told OurAmazingPlanet.

The quakes help map out how the mine collapsed. At present, there is no sign that seismicity gave warning of the coming collapse, study co-author Michael McCarter, a University of Utah professor of mining engineering, said in a statement. The researchers plan to investigate whether any of the tiny tremors could have given warning, he said.

Kubacki said the cave-in was cone-shaped, with the narrowest end of the cone pointing down into the Earth. Since the catastrophe, the earthquakes have shifted to the edges of the cone, on the west and east ends of the collapse zone.

The new study also shows that the collapse area goes farther than once thought, all the way to the western end of the mine, beyond where the miners were working, Kubacki said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A 2008 seismic study by University of Utah seismologist Jim Pechmann, who is not involved in the current research, calculated the collapse area covered 50 acres. Pechmann and his university colleagues also proved that the collapse was not caused by an earthquake, as initially claimed by the mine's owners.

The earlier studies also found a giant vertical crack opened in the room where the miners were working, collapsing the roof. Though it dropped only about a foot, the pressure exploded the supporting pillars, filling the room with coal and rubble within seconds, according to the scientists' reports.

Kubacki is now comparing the Crandall Canyon seismicity to other coal mines in Utah, in an effort to better understand mine earthquakes and improve safety. The current study shows remote monitoring can reveal subtle patterns of tremors, meaning mine owners needn't install expensive monitoring equipment deep in mines, he said.

"This research is a starting point to monitoring mine seismicity and potential collapses," Kubacki said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus