Protecting Ozone Layer Also Slowed Global Warming

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

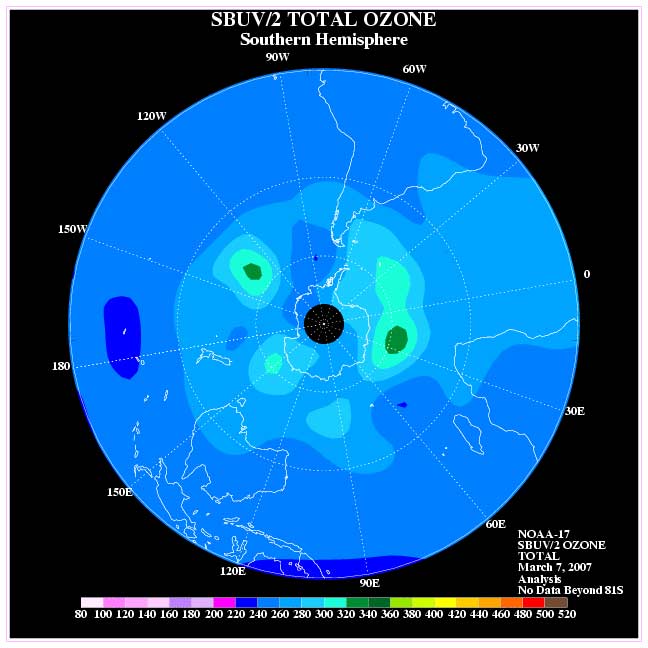

Global warming would be substantially worse right now if not for an international agreement in the 1980s that banned the use of ozone-destroying chemicals, a new study finds.

Nations around the world signed the Montreal Protocol in 1987 to control the production and use of substances that deplete the ozone layer, which shields the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

While these chemicals, such as chlorofluorocarbons (formerly used in air conditioners), eat up ozone, they also act as greenhouse gases.

By curbing their use, the pact has also cut in half the amount of greenhouse warming that would have occurred by 2010 had these substances continued to build unabated in Earth’s atmosphere, according to the study published in the this week’s online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The amount of warming that was avoided is equivalent to 7 to12 years of an increase in carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere.

“The participants in the Montreal Protocol have done something very good for our climate,” says study author and NOAA scientist David Fahey. “While addressing ozone depletion, they also provided an early start on slowing climate change.”

The quantity of greenhouse gas curbed by the Montreal Protocol is equivalent to five times the reduction target for the first phase of the Kyoto Protocol, a 2005 international agreement to address climate change, according to Fahey and his colleagues. The United States did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus