World's Strangest Creature? Part Mammal, Part Reptile

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

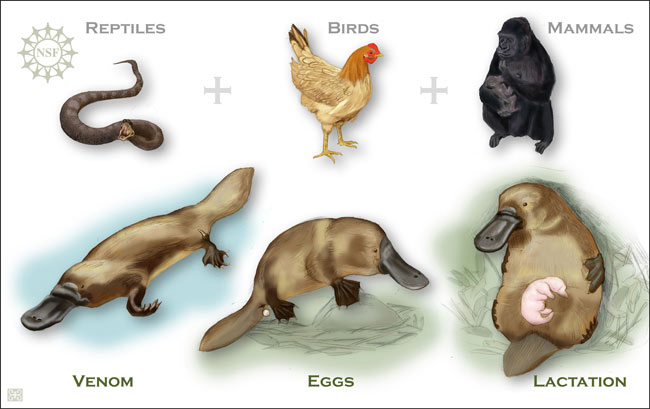

The platypus sports fur like a mammal, paddles its duck feet like a bird and lays eggs in the manner of a reptile.

Nature's instruction manual for this oddball, it turns out, is just as much of a mishmash.

Researchers just mapped the genome of a female platypus from Australia. The genetic sequence of this Aussie monotreme (a type of mammal) is detailed in the May 8 issue of the journal Nature.

"The platypus is a very ancient offshoot of the mammal tree, so it was 166 million years ago that we last shared a common ancestor with platypuses," said study team member Jenny Graves, head of the Comparative Genomics Group at the Australian National University. "And that puts them somewhere between mammals and reptiles, because they still maintain quite a lot of reptilian characteristics that we’ve lost, for instance they still lay eggs."

She added, "So we can use them to trace the changes that have occurred as we went from being a reptile, to having fur to making milk to having live-born young."

The primitive mammal lives in burrows in Eastern Australia dug along the banks of streams and rivers that it relies on for food. Its flat, streamlined body extends just 20 inches (50 centimeters), tipped with a tail that resembles a ping-pong paddle and four webbed feet. The platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) is one of only two mammals — the other is the echidna (spiny anteater) — that lays eggs. And unlike other mammals, the male platypus can deliver venom from a tiny spur on each hind limb.

To sort out the evolutionary relationships among platypuses and other animals, the team compared the genome of a female platypus nicknamed Glennie with those of humans, mice, dogs, opossums and chickens. (Chickens were included to represent egg-laying animals, such as extinct reptiles, that passed on much of their DNA to the platypus and other mammals in the course of evolution.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At roughly 2.2 billion base pairs, the platypus genome is about two-thirds the size of the human genome, the researchers found. It shares more than 80 percent of its genes with other mammals.

Like humans, platypuses carry an X and a Y chromosome. But unlike humans, the X and Y are not sex chromosomes. "That means we can go right back to the time when our sex chromosomes were just ordinary chromosomes minding their own business and ask well what happened, what made them into sex chromosomes," Graves said.

The researchers revealed the animal has 52 chromosomes, including 10 sex chromosomes.

The genome also included sections of DNA linked to egg-laying and others for lactation. Since the platypus lacks nipples, the pups suckle milk from the mother's abdominal skin.

Another oddity: When paddling through the water, a platypus keeps its eyes, ears and nostrils closed, and its duck-bill serves as an antenna, sensing the faint electric fields surrounding prey. Even so, the platypus genome reveals the animal held onto genes for odor-detection.

The study, which included more than 100 scientists from across the globe, was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI).

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus