New Flying Robots Take Cues From Airborne Animals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

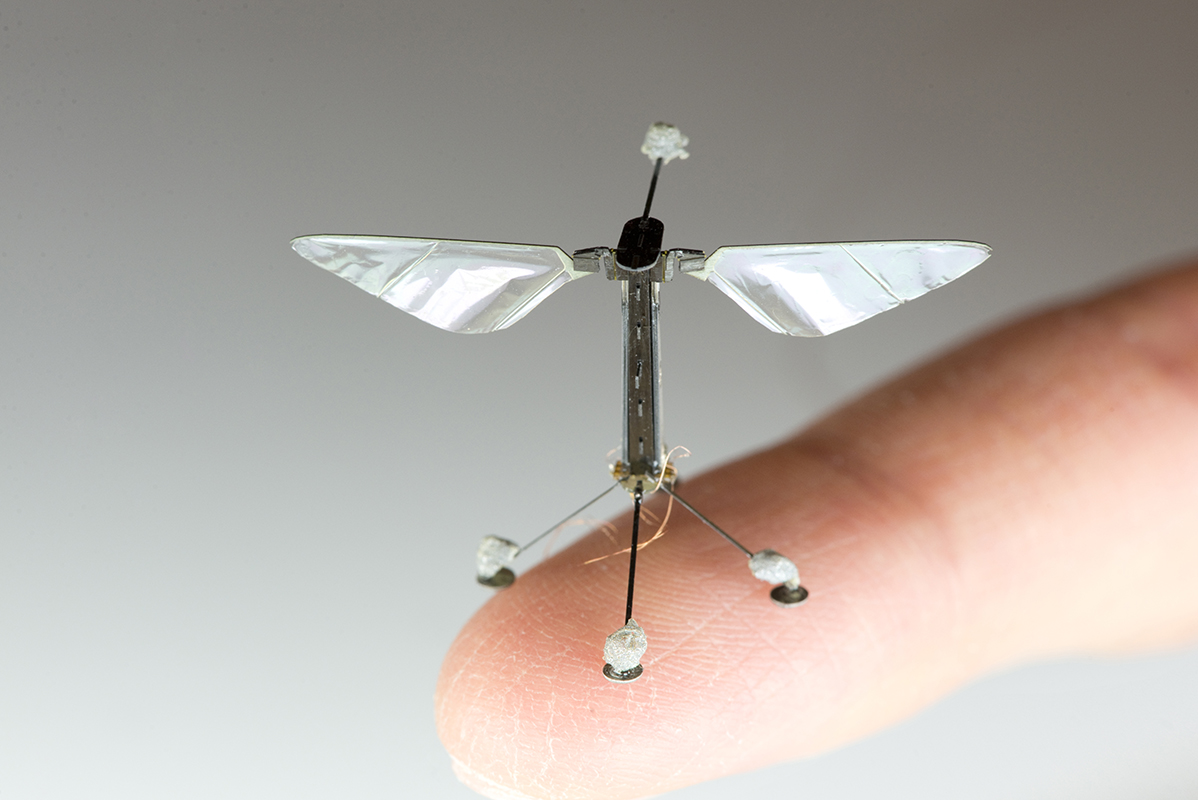

From navigating turbulence, to sleeping midflight, to soaring without a sound, animals' flight adaptations are helping scientists design better flying robots.

Airborne drones and the animals they mimic are featured in 18 new studies published online Dec. 15 in the journal Interface Focus. This special issue is intended "to inspire development of new aerial robots and to show the current status of animal flight studies," said the issue's editor, David Lentink, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University in California.

Though humans have been building flying machines since the 18th century, these new studies revealed that there is still much to be learned from looking closely at how birds, insects and bats take flight, keep themselves aloft and maneuver to safe landings. [Biomimicry: 7 Clever Technologies Inspired by Nature]

Flying drones are rapidly becoming a common sight worldwide. They are used to photograph glorious vistas from above, snap selfies and even deliver packages, as online retail giant Amazon completed its first commercial delivery by drone in Cambridge, in the United Kingdom, on Dec. 7, the BBC reported.

But improving how these robots fly isn't easy, experts said. Fortunately, there are plenty of flying animals that scientists can turn to for inspiration. About 10,000 species of birds; 4,000 species of bats; and well over 1 million insect species have evolved over millions of years to spread their wings and take to the air, and most of these species' flight adaptations haven't been studied at all, Lentink told Live Science.

"Most people think that since we know how to design airplanes, we know all there is to know about flight," Lentink said. But once humans could successfully design planes and rockets, they stopped looking as closely at flying animals as they had in the past, he added.

Now, however, growing demand for small, maneuverable flying robots that can perform a variety of tasks has sparked a scientific "renaissance" and is driving researchers to investigate many open questions about animal aerodynamics and biology, Lentink said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, how are owls able to fly so silently? One team of scientists explored adaptations in owls' wings that could muffle noise, finding that the animals' large wing size and the wings' shape, texture and strategically placed feather fringes all work together to help owls glide soundlessly.

Another group of researchers wondered how frigate birds — a type of seabird that can fly without stopping for days at a time — could sleep "on the wing" during long migrations. The scientists collected the first recordings of in-flight brain activity for these birds, discovering that the animals were able to "micro nap" to rest both brain hemispheres at the same time.

Some scientists puzzled over how fruit flies were able to stay aloft even if their wings were damaged, learning that the insects compensated for missing pieces in wing membranes by adjusting their wing and body movements, enabling the bugs to fly even if half a wing had been lost.

Other studies described new robot designs that can plunge into watery depths from midair, flap their way through buffeting winds or bend their wings like a bird, for better control.

Silent flight, energy conservation and renewal, adapting to turbulent conditions, and the ability to self-correct for wing damage are all features that could significantly improve current models of flying drones, Lentink told Live Science.

"They need to become more silent," Lentink said of drones. "They need to be more efficient, and they need to fly longer. There's a lot of engineering that still needs to happen. The fact that the first steps are being made right now is really exciting and shows that there is a great future in this."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus