'Lucy' Species May Have Been Polygynous

The ancient relative of humanity dubbed "Lucy" may have been one of a harem of gals who mated with a single male, according to research that suggests her species was polygynous.

Among the earliest known relatives of humanity whose skeletons were made for walking upright was Australopithecus afarensis, the species that included the famed 3.2-million-year-old Lucy. Members of the Australopithecus lineage, known as australopithecines, are among the leading candidates for direct ancestors of the human lineage, living about 2.9 million to 3.8 million years ago in East Africa. [Photos: New Human Ancestor Species Discovered]

To learn more about Lucy's species, researchers investigated the area of Laetoli in northern Tanzania, which previously yielded the earliest known footprints belonging to hominins— humans and related species dating back to the split from the chimpanzee lineage. Those footprints, which date to 3.66 million years ago, were excavated in 1978 at a place dubbed "site G." They are thought to belong to three members of A. afarensis walking in the same direction across wet volcanic ash.

Now, a team of researchers from institutions in Italy and Tanzania has discovered new 3.66-million-year-old tracks at Laetoli that they suggest also belonged to A. afarensis.

"It is amazing that, almost four decades after the original discovery, we have new footprints from the very same sediments," said William Jungers, a paleoanthropologist at Stony Brook University in New York who did not take part in this research. "They could have been made on the same day millions of years ago."

These footprints — a kind of ichnofossil, or trace fossil — reveal that this extinct species may have had major differences in sizes between the sexes. This difference, in turn, suggests that the species might have been polygynous, where males have multiple female mates, the researchers said. Previous research suggested the fact that polygyny leads to a few males monopolizing all females leads to intense competition between males, which favors the evolution of larger males that can better deal with their rivals. [10 Greatest Mysteries of the First Humans]

"For me, the most important implication is that the area might harbor more ichnofossils— knowledge that could be used to solve many problems regarding different aspects of hominins," said lead study author Fidelis Masao, a palaeolithic archaeologist at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

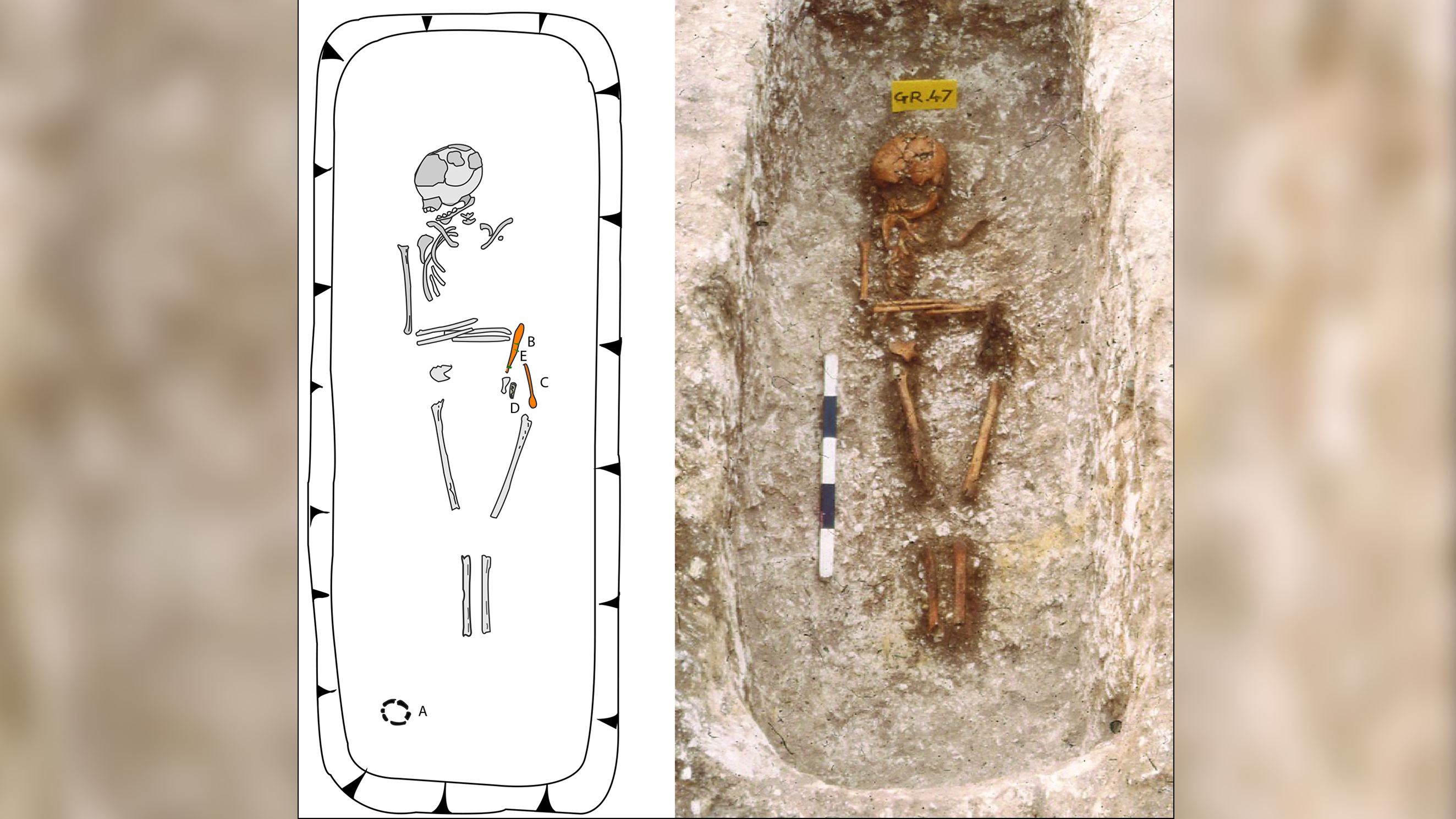

The new sets of footprints belong to two individuals, and were discovered at a place now dubbed "site S," located about 490 feet (150 meters) south of the prints discovered in 1978. Surrounded by dozens of other animal footprints — such as those belonging to a rhino, a giraffe, some horses and guinea fowl — along with raindrop impressions, the new tracks were apparently made on the same surface at the same time, and went in the same direction and at a similar speed as the A. afarensis prints found in 1978. Back when this ancient hominin was alive, the landscape was a bit like it is today — a mix of bushland, woodland and grassland with a nearby forest along the river.

Masao said that, after they had discovered the new footprints, one of the local Maasai workers said to him,"in not too good Swahili, 'Masao umepata choo.'" The worker meant to say, "Masao, you have become famous," but the Swahili word for "famous"is "cheo," not "choo," Masao explained.

"The latter means 'toilet' or 'poop,'" Masao said.

Judging by the impressions each foot made in the earth and the distance between each track, the researchers could estimate the size and weight of the individuals who made each set of prints. One individual was likely male, about 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m) tall and 98.5 lbs. (44.7 kilograms). The other was likely female, about 4 feet 10 inches (1.46 m) tall and 87 lbs. (39.5 kg), the researchers said. [In Photos: 'Little Foot' Human Ancestor Walked With Lucy]

The estimates from the new male exceed the estimated height and weight of the tallest previous specimen from Laetoli by more than 7.8 inches (20 cm) and 13.2 lbs. (6 kg). Indeed, the estimated size of the new male individual "makes him the largest Australopithecus afarensis specimen identified so far," said senior study author Giorgio Manzi, a paleoanthropologist at Sapienza University in Rome.

Study co-author Marco Cherin, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Perugia in Italy, noted that he and some of the other researchers walked barefoot at the site to avoid damaging the tracks. "We realized that the feet of many of us fit well with the footprints," Cherin told Live Science.

Similarly, the new female is an estimated 1.2 to 1.6 inches (3 to 4 cm) taller than previous female specimens from Laetoli, the researchers said. This new female is also more than 11.8 inches (30 cm) taller than Lucy.

When these new prints are considered together with the prints discovered in 1978, it suggests "several early bipedal hominids moving as a group through the landscape, after a volcanic eruption and a subsequent rainfall," Manzi told Live Science.

One tentative conclusion from these findings is that the group might have consisted of "one male, two or three females, and one or two juveniles," Manzi said. This idea, in turn, potentially suggests that this male — and, therefore, other males in the species — may have had more than one female mate, Cherin said. However, Cherin did caution that "the inferences on sexual dimorphism [differences between the sexes] and on social structure need to be evaluated carefully."

These findings suggest that sexual dimorphism may have been much more pronounced and certain in A. afarensis than scientists had thought. Prior work found that high sexual dimorphism is linked with polygyny — for example, in gorillas. In contrast, humans and their closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, are only moderately sexually dimorphic.

Scientists have hotly debated the level of sexual dimorphism in A. afarensis for nearly 40 years, "with some researchers supporting the notion of an only moderate degree of dimorphism, not too different from Homo sapiens, while the rest of the world supports the idea of marked sexual dimorphism," Cherin said. Their findings are "strong evidence that this fossil hominin was characterized by a strong variation in size."

Future research will aim to excavate more tracks from Laetoli to learn more about how these ancient relatives of humanity walked, Cherin said.

The authors of this new study "should be applauded for their efforts and the exciting but preliminary results," Jungers told Live Science. "There is much more analytical work to be done. I'm sure the authors would agree and look forward to the 'next steps' in their research program."

Masao, Cherin, Manzi and their colleagues detailed their findings online Dec. 14 in the journal eLife.

Original article on Live Science.