2,500-Year-Old Burial Hints at Ancient Cannabis Use

About 2,500 years ago, mourners buried a man in an elaborate grave, and covered his chest with a shroud made of 13 Cannabis plants, according to a new study.

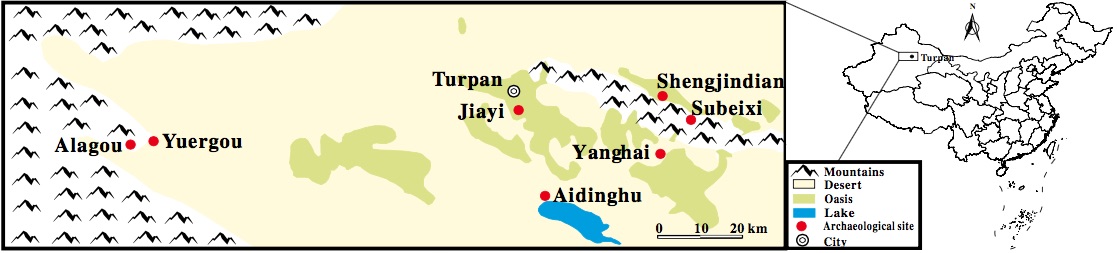

The grave is one of a select few ancient Central Eurasian burials that archaeologists have found to contain Cannabis. This particular grave, located in northwestern China, sheds new light on how prehistoric people in the region used the plant in rituals, the researchers said.

The finding, "a remarkable archeobotanical [also spelled 'archaeobotanical'] discovery in its own right," came about after the region's modern inhabitants decided to build a new cemetery next to a picturesque oasis, the researchers wrote in the study. However, construction workers soon found that an ancient graveyard was in their way. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

Archaeologists came to the site and quickly discovered a bounty of artifacts buried in the graves — bows, arrows and the remains of domesticated animals, including goats, sheep and a horse skull — indicating that these ancient people engaged in both hunting and animal husbandry, the researchers said.

The ancient Jiayi cemetery likely belonged to the Subeixi culture, according to analyses of earthenware pots found in some of the graves. The Subeixi were the first known people to live in the arid Turpan Basin (what's now western China) starting about 3,000 years ago, and eventually transitioned into a farming society, according to Archaeology.about.com.

Cannabis shroud

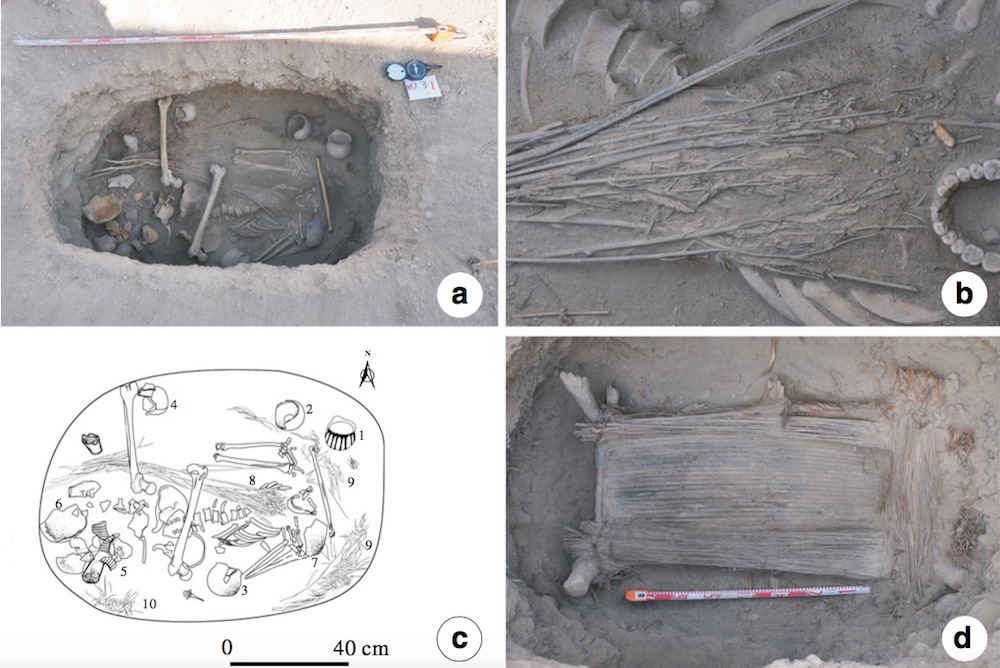

In all, the archaeologists uncovered 240 ancient tombs, including that of the man with the Cannabis shroud in tomb M231. The remains of the man, a Caucasian about 35 years old when he died, were lying on a bed frame made of wooden slats. His head rested on a pillow created from common reeds, and the grave was filled with earthenware pots, the archaeologists found.

But more astonishingly, "13 nearly whole female Cannabis plants were laid diagonally across the body of the deceased like a shroud, with the roots and lower parts of the plants grouped together and placed below the pelvis," the researchers wrote in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Cannabis plants were long — about 19 to 35 inches (49 to 90 centimeters) in length, and reached to just under the man's chin on the left side of his face, the researchers said.

Immature fruits on the Cannabis plant suggest that they were uprooted in late summer, indicating that the man was buried in late August or early September, the researchers said.

Although the grave is between 2,400 and 2,800 years old, according to radiocarbon dating, the Cannabis remained intact because the region is bone-dry, the researchers said. There are years when it doesn't even rain. But river deposits, such as sand and pebbles — as well as the ancient remains of water plants, including horsetails and reeds — indicate that the ancient Jiayi cemetery once sat next to a riverbed, the researchers said.

"Weedy" graves

Grave M231 is hardly the only ancient Cannabis-containing burial. The Turpan Basin has another Subeixi graveyard called the Yanghai cemetery, which is also dated to the first millennium B.C., according to a 2006 study in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology. One of its burials had a large supply of processed Cannabis flowers in two containers — a coiled leather basket and a wooden bowl — that sat next to a male corpse, the 2006 study found. [In Photos: Ancient Silk Road Cemetery]

The grave didn't hold any evidence of hemp clothing or rope, which are made of the Cannabis plant. Rather, the plant's large seeds and high presence of cannabinol (a degraded product of the plant's psychoactive tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC) suggest that the Cannabis was used as a psychoactive substance, the researchers said.

Another ancient Yanghai tomb contained Cannabis flower heads, indicating that people may have used it for medicinal purposes, the researchers said.

In addition, archaeologists have found Cannabis in graves located in tombs of the Pazyryk culture in southern Siberia, where there is also evidence of the plant's "ritualistic if not psychoactive usage," the researchers wrote in the study. Experts also discovered the plant in an Altai Mountain Pazyryk-culture tomb of a woman who had died of breast cancer and possibly used the Cannabis to help her cope with symptoms, the researchers said.

"Apparently, medicinal — and possibly spiritual, or at least ritualistic — Cannabis use was a widespread custom among Central Eurasian peoples during the first millennium before the Christian era," the researchers wrote in the study.

The findings were published online Sept. 20 in the journal Economic Botany.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.