Feel Controlled by Your Hunger? New Study May Show Why

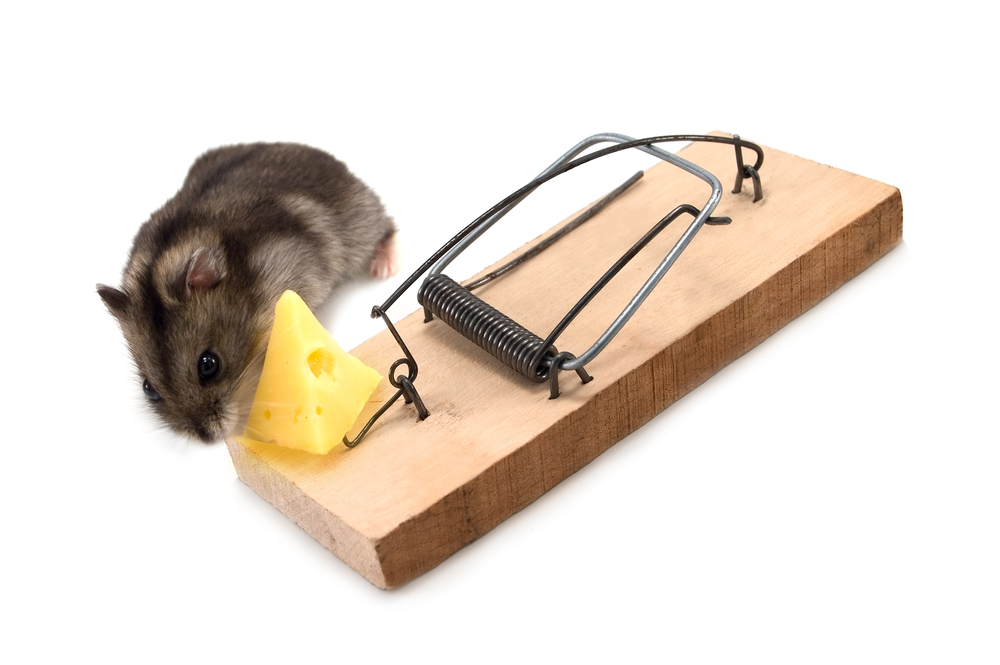

Have you ever felt like you would do just about anything to satisfy a hunger craving? A new study in mice may help to explain why hunger can feel like such a powerful motivating force.

In the study, researchers found that hunger outweighed other physical drives, including fear, thirst and social needs.

To determine which feeling won out, the researchers did a series of experiments, according to the study, published today (Sept. 29) in the journal Neuron. [The Science of Hunger: How to Control It and Fight Cravings]

In one experiment, the mice were both hungry and thirsty. When given the choice of either eating food or drinking water, the mice went for the food, the researchers found. However, when the mice were well-fed but thirsty, they opted to drink, according to the study.

In an experiment meant to pit the mice's hunger against their fear, hungry mice were placed in a cage that had certain "fox-scented" areas and other places that smelled safer (in other words, not like an animal that could eat them) but also had food. It turned out that, when the mice were hungry, they ventured into the unsafe areas for food. But when the mice were well-fed, they stayed huddled in areas of the cage that were considered "safe," the researchers found.

Hunger also outweighed the mice's social needs, the researchers found. Mice are usually social animals and prefer to be in the company of other mice, according to the study. When the mice were hungry, they opted to leave the company of other mice to go get food.

"Hunger-tuned neurons"

To figure out why hunger prevailed over other feelings, the researchers looked into the brains of the mice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They focused on a specific type of nerve cell that has been linked to hunger. In the study, the researchers placed tiny fibers into the brains of the mice that gave them the ability to turn these nerve cells on and off.

When the researchers activated the nerve cells, the mice that had been fed acted the same way as the mice that had not been fed. In other words, "turning on" these nerve cells seemed to turn on hunger, and thus drove the mice to eat.

The findings suggest that these "hunger-tuned neurons" can "anticipate the benefits of searching for food, and then alter behavior accordingly," Michael Krashes, a principal investigator at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the senior author of the study, said in a statement.

The decision to search for food instead of looking for water or hiding from predators has important evolutionary implications, Krashes said. Mice, as well as humans, are constantly presented with the chance to pursue an "array of behaviors," Krashes said.

But "we can't pursue all those behaviors at once," he said. Rather, we have to choose which feelings are most important to address during times of need. "Evolutionarily speaking, animals that consistently picked the right motivations over others have survived, while other animals have not," Krashes said.

Originally published on Live Science.