6 Big Mysteries of Alzheimer's Disease

The mysteries of Alzheimer's

Despite intensive, worldwide research efforts for more than three decades to better understand Alzheimer's disease, there are still numerous mysteries surrounding the condition.

Alzheimer's disease is a slowly progressing brain disorder. In people with the condition, abnormal deposits of a protein called amyloid-beta forms sticky plaques in the brain, and strands of the protein tau twist around, causing tangles that ultimately kill brain cells and cause a loss of memory, thinking and reasoning skills.

About 5.4 million Americans currently have Alzheimer's disease, and the number is expected to grow rapidly in the coming years as a larger share of the population ages, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [7 Ways to Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease]

Researchers are now aiming to better understand what underlies the disease, as well as improving methods of detection, prevention and treatment.

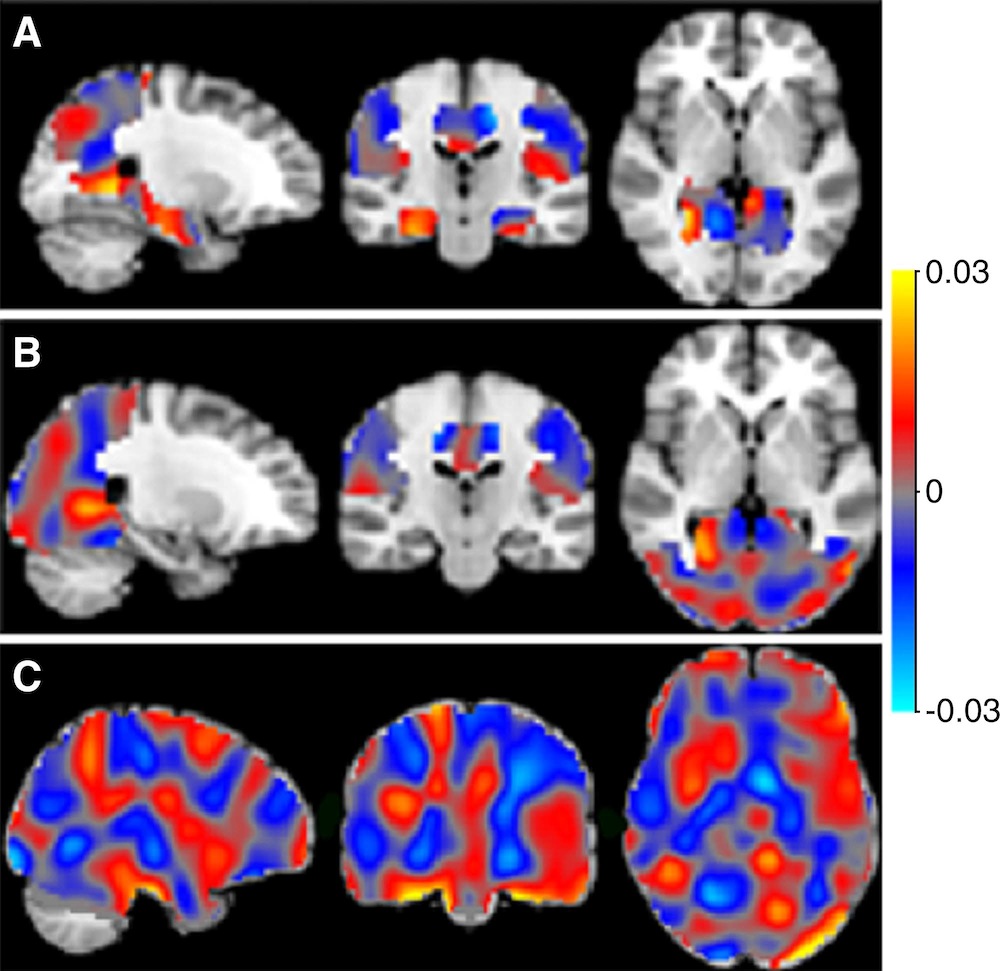

In the past 15 years, biomarkers (biological markers), including new brain-imaging techniques such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans, and new methods to analyze cerebrospinal fluid have helped researchers to detect early changes in brain function in people with Alzheimer's, said Dr. John Morris, a professor of neurology and director of the Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

For example, using radioactive tracers that can bind with amyloid protein deposits in plaque and tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles, researchers can now use PET scans to peer inside the brain to detect whether Alzheimer-related changes are present, Morris said.

In addition, they can perform a spinal tap to withdraw a sample of cerebrospinal fluid, and use it to measure whether a person has low concentrations of amyloid beta protein and high concentrations of tau protein, which have both been linked with a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, he told Live Science.

Despite these advances, there are many aspects of Alzheimer's disease that researchers only partially understand, said Dr. Dennis Selkoe, co-director of the Ann Romney Center for Neurological Diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, who has been conducting research to uncover the causes of Alzheimer's disease for more than 30 years.

For people with Alzheimer's disease and their loved ones, the most important mystery to solve is finding a safe and effective treatment for this neurodegenerative disorder, Selkoe said.

Here are the six biggest mysteries of Alzheimer's disease, according to these two researchers, and a look at the work that's being done to solve them.

Mystery: What will be a safe and effective treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

Although this is not a complete mystery because many clinical trials of experimental treatments are underway, researchers are working hard to find a safe and effective treatment to slow down Alzheimer's, or even prevent it from developing, Selkoe said.

Selkoe has helped pioneer extensive research on the "amyloid hypothesis," the idea that an imbalance between the production and removal of a protein called amyloid beta in the brain is what triggers Alzheimer's disease.

There are certain "sticky" amyloid proteins that build up and form plaque in the brain that can short-circuit cells involved in memory, Selkoe said. It's possible that if there were therapies that could control or reduce the accumulation of this plaque, people would not become forgetful, he said.

Selkoe said that he was encouraged by the results of a recent investigational trial of a drug called aducanumab, which is an antibody-based immunotherapy. The drug was given intravenously every month for one year to 165 people with early or mild Alzheimer's disease, who had evidence of plaque buildup in the brain.

Within six months, participants taking the drug began to show declines in the amount of amyloid beta plaque, compared with those taking a placebo. By one year, more clearing of amyloid beta had occurred, according to the study findings reported in August in the journal Nature. The researchers found that there appeared to be a slowing of cognitive decline in a dose-dependent manner, meaning that the patients who were given higher doses showed a greater degree of slowing. [7 Ways the Mind and Body Change With Age]

Participants taking the drug didn't get better, but there was a stabilization of the disease's progression, Selkoe told Live Science. As for the drug's safety, about 30 percent of participants experienced a short-term change in the balance of the watery fluid in the brain, a side effect that went away by itself during the trial, and a few people had headaches, he said.

For now, this antibody-based therapy looks effective and appears safe, and a larger trial of this drug and other antibody-based treatments is underway, Selkoe said.

Mystery: Why have clinical trials of some highly promising drugs failed to show positive results?

One reason for the discouraging results of some high-profile clinical trials of promising therapies over the last 15 years is that they included people who may not have had Alzheimer's disease. Because of an imperfect testing process, some participants may have been included in these trials who had symptoms similiar to Alzheimer's but actually had another form of dementia, Morris told Live Science. Now, people in experimental drug trials need to test positive for biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease before they can participate in the research, he said.

Another reason the drugs did not appear to work in the trials could have been that the participants' disease was too far advanced, Morris said. By the time symptoms of declining thinking and memory skills appear in older adults, the brain has already been damaged by plaques and tangles, and there has been a loss of brain cells, he said.

Now that biomarkers can better identify which older adults should be in drug trials, researchers could introduce experimental medications in people at earlier stages of the disease — years or decades before symptoms appear — to see if the medicines might slow down or halt the Alzheimer's disease process in the brain, Morris said.

Mystery: How do brain cells die once amyloid plaque gets deposited?

Many aspects of the disease process underlying Alzheimer's remain unclear to researchers. But it's possible that the disease begins with the abnormal metabolism of amyloid plaque in the brain that sets off a toxic cascade of events, Morris said. These events may activate immune system cells that trigger inflammation, or there could be some other type of injury to brain cells, he explained.

Because of the many wide-ranging brain changes caused by the disease, treatment may someday involve the use of multiple drugs that target different aspects of the Alzheimer's disease process, not just the buildup of amyloid deposits in the brain, Morris said.

In fact, some researchers suspect it's unlikely that there will be a single drug treatment for Alzheimer's disease. It's more probable that there will be a cocktail of medications, like the treatments used to successfully treat AIDS and some cancers, which are aimed at several different targets. These medications could target the underlying disease itself, as well as stopping or delaying damage to the brain cells that worsens its symptoms.

Mystery: What is the relationship between the plaques and the tangles found in the brain?

Since 1906 when the disease was first described by Alois Alzheimer, researchers have known about the presence of plaques and tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. But one of the big mysteries of the disease is how these two hallmarks of the disease might be related, Selkoe said.

Scientists have unraveled part of the answer to this mystery by discovering that the plaques develop in the brain first, before the tangles, Selkoe told Live Science. It's also known that the buildup of amyloid beta protein causes injury to nerve cells, and that strands of tau protein twist and form tangles inside nerve cells, he said.

But researchers don't yet know exactly how these plaques and tangles affect brain function, eventually leading to the memory problems, behavioral changes and other symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Selkoe said. And they also don't know whether amyloid in plaque and tau in tangles work separately, or together, to damage nerve cells, he added.

These are some reasons why therapies aimed solely at reducing amyloid buildup might not be enough by itself to treat Alzheimer's disease, and why there may also be a need for a drug that helps lower tau levels, Selkoe said.

Mystery: What does inflammation have to do with Alzheimer's disease?

Another characteristic brain abnormality of Alzheimer's disease is inflammation — meaning the excessive action of the immune cells in the brain.

It's unclear whether inflammation is a result of having Alzheimer's disease, or whether the inflammatory process plays a role in its development. It's also possible that inflammation is both a cause and effect of the disease. [3D Images: Exploring the Human Brain]

What's known is that there are immune cells in the brain known as microglia that are normally present to clean up infections, which helps protect the brain, Selkoe said. There is also good evidence that these immune cells get upset about the buildup of too much amyloid in the brain, which makes them aggravated, causing the microglia to release too much protein, he said.

The release of too much protein by microglia can cause trouble at the synapses, or connections, between nerve cells, Selkoe said.Scientists wonder whether drugs aimed at controlling inflammation in the brain could also help control memory problems, he said.

Mystery: Why are certain regions of the brain more vulnerable to Alzheimer's disease?

"There is a lot that researchers don't understand about how Alzheimer's disease is manifested in a particular person," Morris said.

Not everyone has memory problems initially: Some people first develop changes in their behavior, such a a lack of empathy or a loss of inhibition, while others may have language difficulties, such as problems expressing themselves with language or hesitatating when they are speaking because they can't find the right words, Morris said. Still others may have problems interpreting visual stimuli, and complain of blurred vision or difficulty reading and writing, he said.

Scientists don't know why people have different presentations of the disease, although it usually first affects short-term memory, such as learning new information, and it typically involves forgetfulness, Morris said. It's unclear what causes certain brain regions to be affected first by the disease, while many other brain regions, by and large, are still functioning normally, he said.

As Alzheimer's disease progresses, regions of the brain beyond those involved in memory and thinking become impaired, and in advanced stages, a person ends up with widespread brain disease, Morris said. The use of biomarkers is allowing scientists to see which regions of the brain are being targeted in the early stages of the disease, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.