10 Mysterious Deaths and Disappearances That Still Puzzle Historians

Almost every day, historians and archaeologists reveal more and more secrets of the past, but several of the biggest historical mysteries (and archaeological ones) still puzzle researchers after decades — or sometimes even centuries — of investigations.

Here are 10 of the most enduring stories of mysterious deaths and disappearances that still puzzle historians.

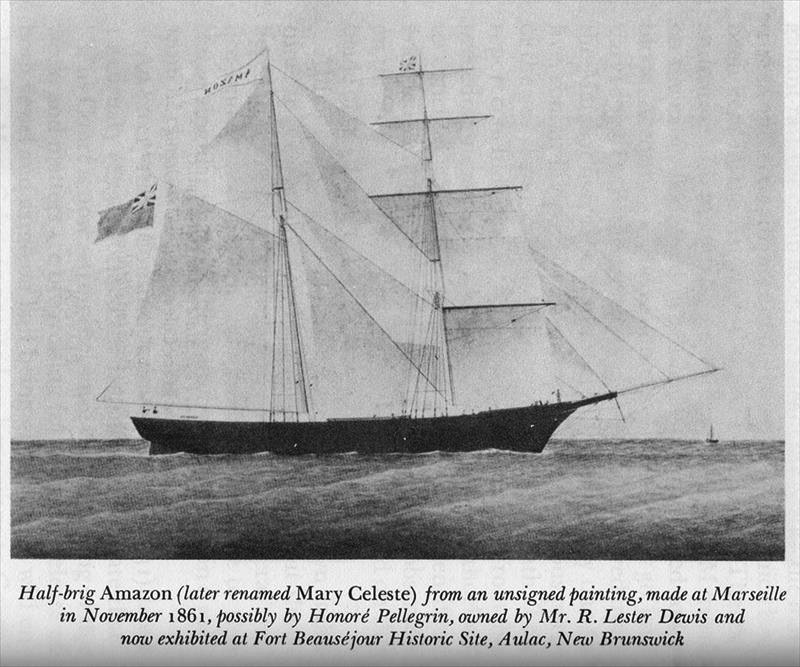

The Mary Celeste

The American merchant ship Mary Celeste was found drifting at sea on Dec. 5, 1872, about 400 miles (640 kilometers) east of Portugal’s Azores Islands, in the eastern Atlantic. The ship, under partial sail when it was intercepted by a Canadian vessel, was carrying a nearly full cargo of casks of industrial alcohol, as well as enough food and water to last for many months. But one of the lifeboats on the merchant ship was missing, and there was no sign of the crew, although their belongings were found still in their bunks.

The Mary Celeste had sailed from New York, almost a month before it was sighted, bound for Genoa in Italy with 10 people aboard: seven crewmen and the ship’s captain, the captain's wife and the couple's two-year-old daughter. But no sign of them was ever found.

In 1884, a few years before the first Sherlock Holmes mysteries appeared in print, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published a fictional first-person account by a survivor of a ship called the "Marie Celeste." In Doyle's story, the crew was murdered by a vengeful serial killer among the crewmen. The story became more famous than the original case, and was even presented as a true account in some newspapers, including the Boston Herald, according to a report in a 1913 report edition of The Strand magazine. Several researchers have speculated that the real Mary Celeste was abandoned because the crew feared an explosion from alcohol fumes leaking from the casks in the hold. Others speculate that the ship was attacked by Moroccan pirates, who carried away the people onboard but left the cargo.

In 2007, documentary filmmaker Anne MacGregor suggested the ship may have been abandoned after it took on water in bad weather and the captain saw an opportunity to make for land in a lifeboat. But the occupants of the lifeboat appeared to have been lost at sea, while the abandoned Mary Celeste was able to ride out the storm.

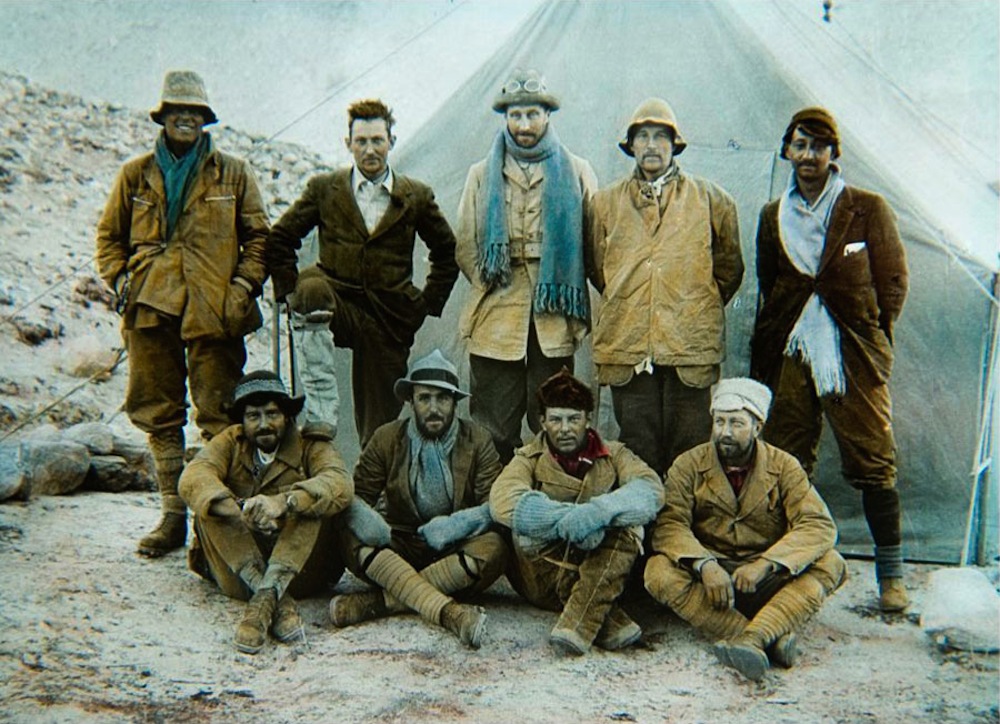

Mallory and Irvine on Everest

On June 4, 1924, British mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine set out from an advanced base camp high on the North Col of Mount Everest, in an attempt to become the first people to reach the summit of the world's highest mountain. They were sighted 4 days later by another member of their expedition, climbing on the mountain’s North-East Ridge, about 800 vertical feet (245 meters) below the summit. But then clouds closed over the ridge, and the two men were never seen again.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Historians and mountaineers have long speculated that Mallory and Irvine may have survived the climb to the summit of Mount Everest, at an altitude of 29,029 feet (8,848 meters), but then died during their descent from the mountain, probably on June 9, 1924.

In 1933, Irvine's ice ax was found high on the mountain, confirming the mountaineers had reached an altitude of 28,097 feet (8,564 m). In 1999, an expedition found Mallory’s remains, on Everest's North Face, at an altitude of nearly 27,000 feet (8,230 m). Some climbers have claimed to have seen another body in the area — possibly that of Irvine — but while the finds are intriguing, the question of whether Mallory and Irvine reached the summit before they died remains a subject of debate.

The last flight of Amelia Earhart

When American aviator Amelia Earhart set out to become the first woman to fly around the world, she was already one of the most famous women in the world. Five years earlier, in May 1932, she had made a name for herself as the first woman to fly solo non-stop across the Atlantic. And in 1935, Earhart made the first solo flight from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California. As such, the world was watching in July 1937, when the plane carrying Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan on their round-the-world attempt went missing over the Pacific Ocean.

Earhart and Noonan took off on July 2, from Lae in Papua New Guinea, bound for Howland Island, their next refueling stop, around 2,550 miles (4,110 km) away, across the ocean. As they approached what they thought was Howland Island, Earhart was able to make radio contact with a U.S. Coast Guard ship stationed to guide them in. But, Earhart's last radio messages indicated she was unable to locate either the ship or the island. [In Photos: Searching for Amelia Earhart]

The U.S. Coast Guard ship began a search immediately, joined by U.S. Navy ships in the days that followed. No remains of the aircraft were found, and the official search effort — at that time, the largest and most expensive in U.S. history — was called off after two weeks.

Still, historical researchers have never given up on trying to find Earhart. Among recent efforts to find out just what happened to America’s pioneering aviator, researchers equipped with underwater robots have been exploring the waters around Nikimaroro Atoll, an island in the Kiribati region, for clues that they hope may lead them to the wreckage of her aircraft.

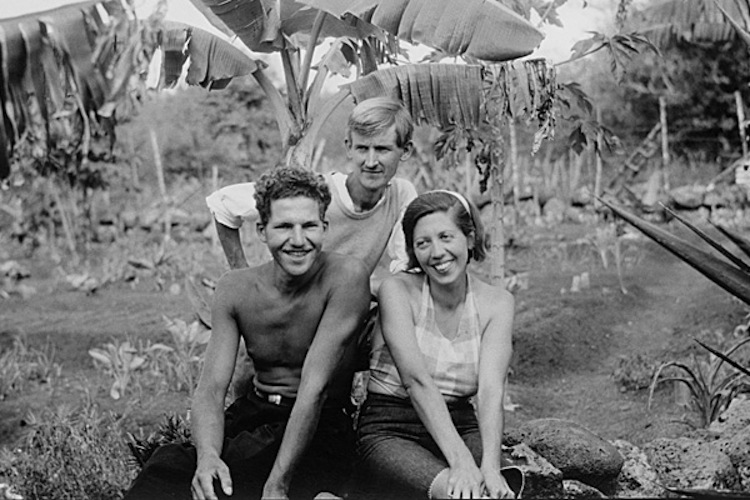

The Baroness of the Galapagos

Eloise Wehrborn de Wagner-Bosquet, known as the "Baroness of the Galapagos," was a young Austrian woman who disappeared in 1935 on the remote island of Floreana in the Galapagos Archipelago, in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Floreana had become famous in Germany after it was "colonized" in 1929 by a German couple, Friedrich Ritter and Dore Strauch, who eked out a primitive living in a house made from rocks and driftwood. Their celebrity attracted other German families to Floreana, seeking what they saw as a utopian lifestyle.

In 1933, the “Baroness” arrived, along with her two young German lovers, Robert Philippson and Rudolf Lorenz, and an Ecuadorian servant. After setting up house on the island, she announced plans to build a luxury hotel — and in the meantime, built a reputation for flamboyant living among the simple colonists of Floreana.

On March 27, 1934, the Baroness and her lover Philippson disappeared. Another German colonist claimed they had embarked on a passing yacht bound for Tahiti, but there were no records of such a yacht visiting the Galapagos at that time. A few days later, the Baroness’s other lover, Rudolph Lorenz, hurriedly left Floreana in a boat with a Norwegian fisherman, bound for the South American mainland. Their mummified bodies were found months later, stranded on a waterless island where their boat had foundered.

Researchers speculate that Lorenz killed the Baroness and Philipson, and that other colonists helped him cover up the murders, but the disappearance of the Baroness of the Galapagos has never been solved.

The South Pole poisoning

On May 12, 2000, near the middle of the dark Antarctic winter, an Australian astrophysicist named Rodney Marks died from a sudden and mysterious illness at the Amundsen–Scott Station, the American scientific research base located at the geographic South Pole.

Because winter flights to the South Pole are dangerous, his body was kept frozen until the spring, when it was flown back to New Zealand. An autopsy revealed he had died of methanol poisoning, probably by swallowing methanol without knowing.

After an investigation, which included trying to interview up to 49 people who had over-wintered at Amundsen Scott Station with Marks, the New Zealand police ruled out suicide and thought it unlikely that Marks had accidently poisoned himself.

In 2008, a New Zealand coroner ruled that there was no evidence to suggest foul play. But the events surrounding Rodney Marks' poisoning have never been determined, and the case has gained a reputation in some news media as the first murder at the South Pole.

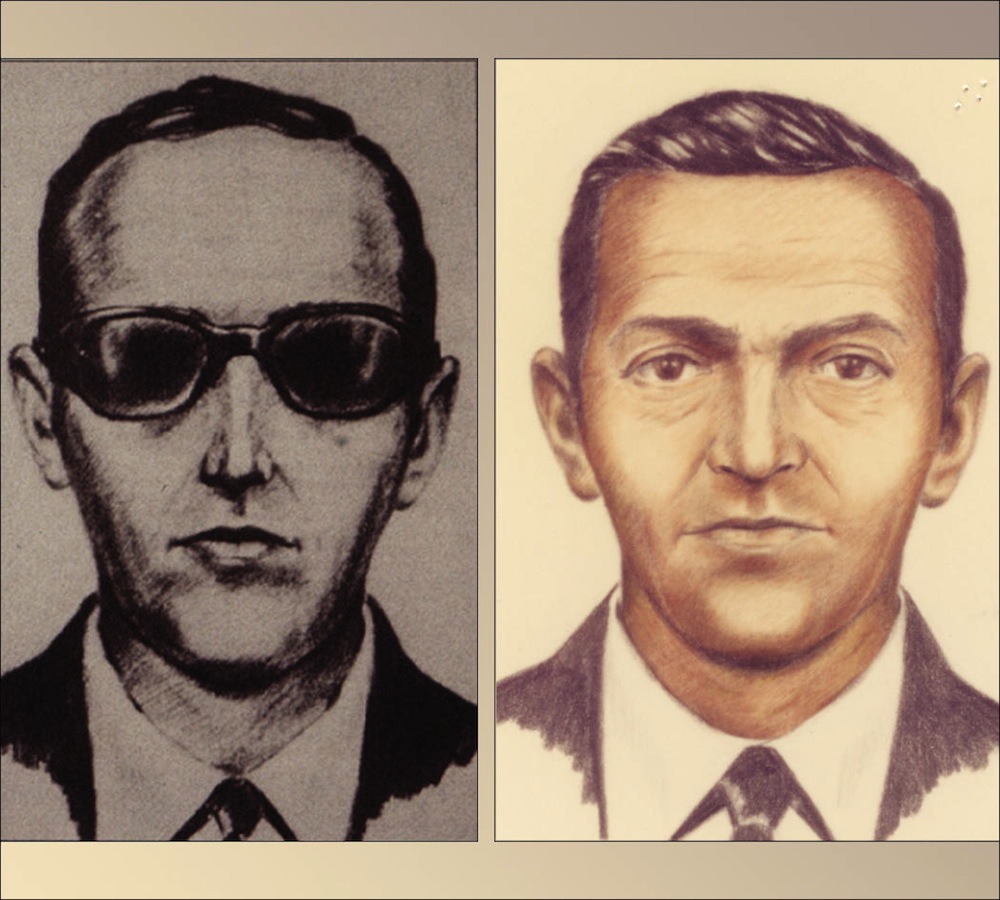

The disappearance of "D.B Cooper"

D.B. Cooper is the popular pseudonym of an unidentified man who hijacked a Boeing 727 flying from Portland to Seattle on the afternoon of Nov. 24 1971. The man boarded with a ticket in the name of "Dan Cooper," which was later misreported by a wire service as "D.B. Cooper." Soon after takeoff, the man told an air steward that he was carrying a bomb, and showed her what looked like a bomb inside his briefcase.

The hijacker then ordered the pilots of the plane to land at Seattle-Tacoma Airport, where he collected a ransom of $200,000 and a parachute, before ordering the plane to take off again. At an altitude of around 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), somewhere over the Pacific Northwest, the hijacker parachuted from the rear steps of the aircraft with the ransom money, and was never seen again.

In spite of an extensive manhunt by the FBI, the hijacker has never been located or identified, and the bureau’s investigators think he probably did not survive his jump from the aircraft. But theories and speculation about the true identity and present whereabouts of "D.B. Cooper" abound.

In 2016, the producers of a documentary on the History Channel claimed to have identified the hijacker as a 72-year-old former military veteran now living in Florida.

The disappearance of Flight 19

Flight 19 refers to a group of five U.S. Navy Grumman TBF Avenger warplanes that disappeared during a daytime training flight off the coast of Florida in December 1945. The strange event was one of the incidents that gave rise to the legend of the Bermuda Triangle.

All 14 airmen aboard the five Avengers were lost, as well as 13 crewmembers on a Navy flying boat that was sent up to search for them. No wreckage or bodies from either the Avengers or the flying boat have ever been found.

The disappearance of Flight 19 helped fuel the idea of a Bermuda Triangle between Florida, Puerto Rico and Bermuda, where there was supposedly a high number of aircraft and ship disappearances — although the U.S. Coast Guard reports that the number is nothing out of the ordinary.

Nonetheless, Flight 19 has become a staple of the Bermuda Triangle mythology, and is often linked to stories of the supernatural or UFOs. For instance, in the opening scenes of Steven Spielberg's 1977 science fiction film "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," the aircraft of Flight 19 are discovered in a desert in Mexico, and the Flight 19 airmen return to Earth in the alien mothership in the final scenes of the film.

The Wallace case

The murder in 1931 of housewife Julia Wallace in her home in Liverpool, in the United Kingdom, has fascinated crime researchers and writers for decades. Wallace’s husband, an insurance salesman named William, had received a message that asked him to visit an address in "Menlove Gardens East" on Jan. 21, 1931. Assuming it was a sales lead, William tried to attend the appointment, but he found that such a street did not exist. He claimed that when he returned home, he found that his wife had been brutally murdered in the living room.

William Wallace was convicted of his wife’s murder, but the conviction was overturned on appeal, so Wallace avoided the sentence of death by hanging. Historical researchers have since speculated that the murder was committed by one of Wallace's co-workers, who had been fired after Wallace accused him of embezzling money.

But in 2013, the British crime writer P.D. James, who researched the case for her own books, wrote in the Sunday Times that she believes Wallace did, in fact, kill his wife. She added that she thought the prank call out to "Menlove Gardens East" on the same night was just a coincidence.

The Taman Shud case

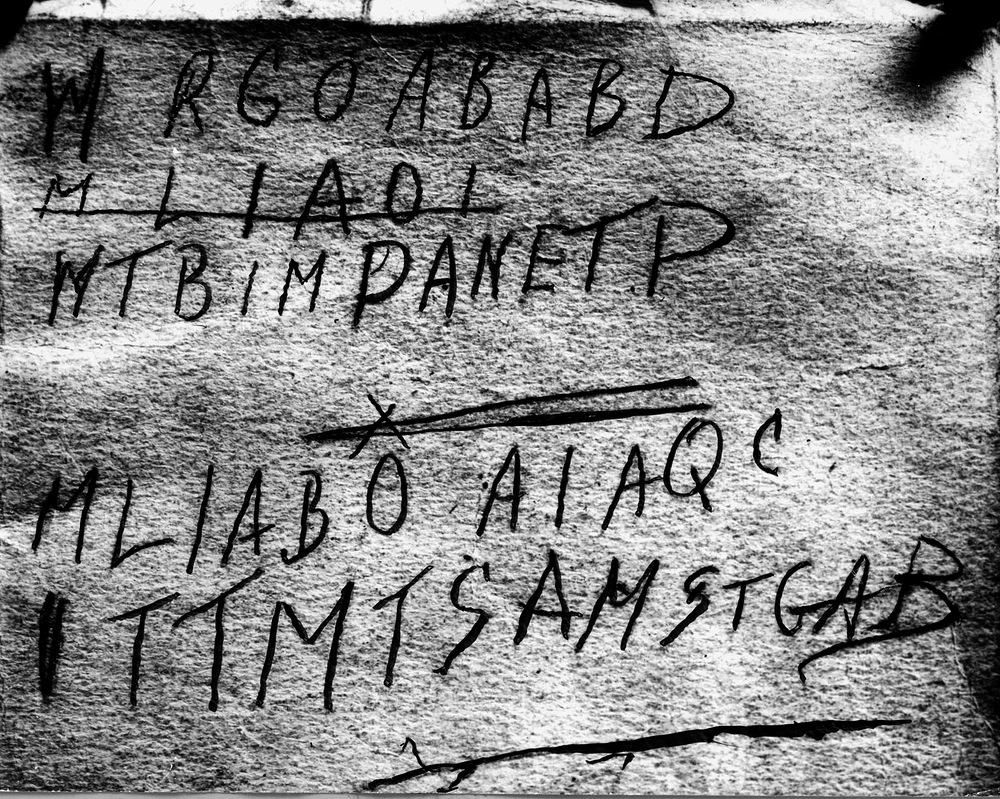

Australia's most mysterious death is known as the Taman Shud case, from the Persian words printed on a scrap of paper in the pocket of a man found dead on a beach south of the city of Adelaide in December 1948.

No identification was found on the body — just a rail ticket, a comb, some cigarettes and the piece of paper with "Taman Shud" printed on it, which means "The End" in Persian. The paper had been torn from a rare edition of a poetry book, the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam," and "Taman Shud" are the last two words from that book.

The mystery deepened when a pathologist who carried out an autopsy suspected the man had been poisoned. The police also found a copy of the poetry book with the words "Taman Shud" torn out, and other pages filled with what appeared to be coded handwritten letters. The book also contained a phone number, which led the police to an Australian woman. She claimed not to know the dead man, and said she had once owned the book but lent it to someone else.

In 2009, Derek Abbott, a professor in the School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the University Of Adelaide, proposed that the coded letters in the book were traces of a manual encryption or decryption of a message using a one-time pad — an espionage technique that can be based on text from a book (in this case, probably the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam").

The finding may give weight to the idea that the death in the Taman Shud case was linked to a foreign spy ring operating in Australia. But, the identity of the dead man remains unknown.

The Dyatov Pass incident

In February 1959, searchers in the northern Ural Mountains in Russia found the abandoned campsite of a ski-trekking party of nine people who had been missing for several weeks. The tent had been torn in half, apparently from the inside, and filled with shoes and other belongings, while several sets of footprints, in socks or barefoot, led away into the snow.

The bodies of all nine hikers were eventually recovered, in May of that year, after the snow thawed. Most had died from hypothermia, but two had fractured skulls, two had broken ribs, and one was missing her tongue.

The case has become known as the Dyatov Pass Incident, after the name of the group leader, Igor Dyatov. The party was mostly made up of students or graduates from a university at Yekaterinburg in Russia’s Sverdlovsk region.

Although the official Soviet investigation found the cause of the deaths was a "compelling natural force" — probably an avalanche — there is still no clear explanation of the events that occurred at Dyatov Pass. Some theories speculate that the party was attacked by wild animals, or that a mass panic caused by low-frequency sounds dispersed the group. There are even highly speculative links to alleged reports that UFOs had been seen in the area near that time.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.