Robots Join Hunt for Amelia Earhart's Plane

U.S. Navy warships and aircraft failed to find Amelia Earhart when the pioneering female aviator vanished in the South Pacific during her second attempt to fly around the world in 1937. This summer, aviation archaeologists have enlisted the help of underwater robots to find the wreckage of Earhart's aircraft.

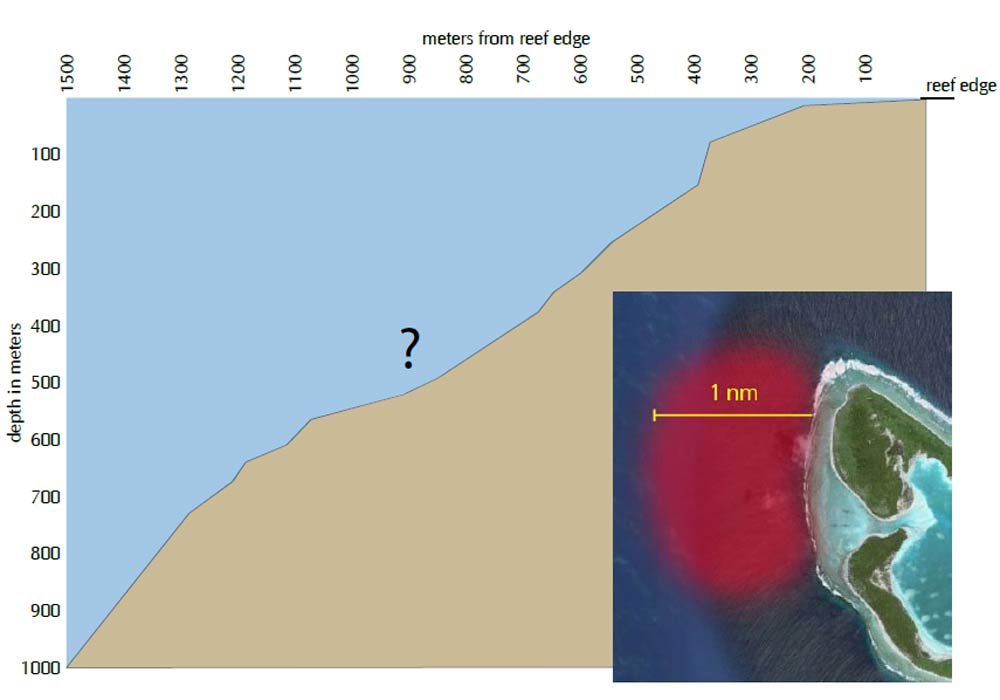

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (or TIGHAR) suspects that Earhart's Lockheed Electra landed on a reef of the uninhabited coral atoll formerly known as Gardner Island and stayed there for several days before waves washed the aircraft over the reef's edge — perhaps enough time for the aviator and her navigator to have sent out radio distress calls. The expedition plans to deploy ship sonar and two robot submersibles to search the slope of the underwater reef for any aircraft parts.

"We will not be recovering anything on this trip," said Richard Gillespie, executive director of TIGHAR. "The objective is to get imagery and photographs of what's there."

The expedition is scheduled to set out aboard the Hawaiian research vessel "Ka'Imikai-o-Kanaloa" from Honolulu on July 2 — the 75th anniversary of Earhart's disappearance. Its underwater robots are capable of searching with sonar and taking black-and-white photos down to a depth of almost 5,000 feet (1,500 meters), as well as checking out sonar targets with high-definition video down to a depth of 3,300 feet (1,000 meters).

An underwater search

An eight-day journey to Nikumaroro (the former Gardner Island) will allow TIGHAR to search the underwater reef slope for approximately 10 days between July 9 and July 19. Success could pave the way for a later expedition to actually recover pieces of Earhart's aircraft.

"If there's wreckage there that can be recovered, we need to know what it is, how big it is, what it looks like, and what it's made of so we can prepare a recovery expedition that has equipment to raise whatever's there," Gillespie told InnovationNewsDaily. "And, equally as important, to conserve it."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The first step in the search relies upon the surface ship's multi-beam sonar — a device capable of mapping the seafloor at depths of almost 7 miles. An autonomous underwater vehicle called Bluefin-21 — made by Bluefin Robotics and operated by Phoenix International Holdings Inc. — can roam the shallows of the underwater reef slope as a programmed drone to help with the sonar mapping. [Navy's Flying Drone Would Launch from Submarine's Trash Disposal]

A second step would rely more upon the torpedo-shaped Bluefin-21 to do a more focused search with its side-scan sonar while taking black-and-white pictures. The crew could recover the collected data, swap out the batteries and reprogram the robot between each six-hour search session.

The third step would try to take an up-close look at suspected aircraft parts with a high-definition video camera — a job for the remote operated vehicle tethered to the surface ship and controlled by a human operator. The TRV 005 robot made by Submersible Systems Inc. even has manipulator arms to move objects around.

Following Earhart's trail

But all the high-tech sonar and robots will only succeed if TIGHAR's hypothesis about Earhart's location proves correct. The group has launched nine expeditions in search of Earhart's lost trail over the past 24 years.

TIGHAR analyzed old radio transmissions originally followed by U.S. Navy and Coast Guard searchers in 1937 to help narrow down the search to Nikumaroro. It also dug up old paperwork from a British colonial physician who described human bones recovered from the island — bones that belonged to a woman fitting Amelia Earhart's profile, according to modern analysis.

Several expeditions uncovered items that could have belonged to Earhart, along with signs of survival living. Such items include a jar that likely contained Dr. Berry's Freckle Ointment (Earhart was known for disliking her freckles), a hand lotion bottle marketed to women in the 1930s, and a bone-handled knife matching the description of a knife listed in Earhart's aircraft inventory. [8 Unsung Women Explorers]

The expeditions also found airplane parts in the ghost village left behind by Pacific Islanders who temporarily settled on Nikumaroro several years after Earhart's disappearance. An old woman living in Fiji — who lived as a young girl on the island — pointed to parts of the island where people had found airplane parts.

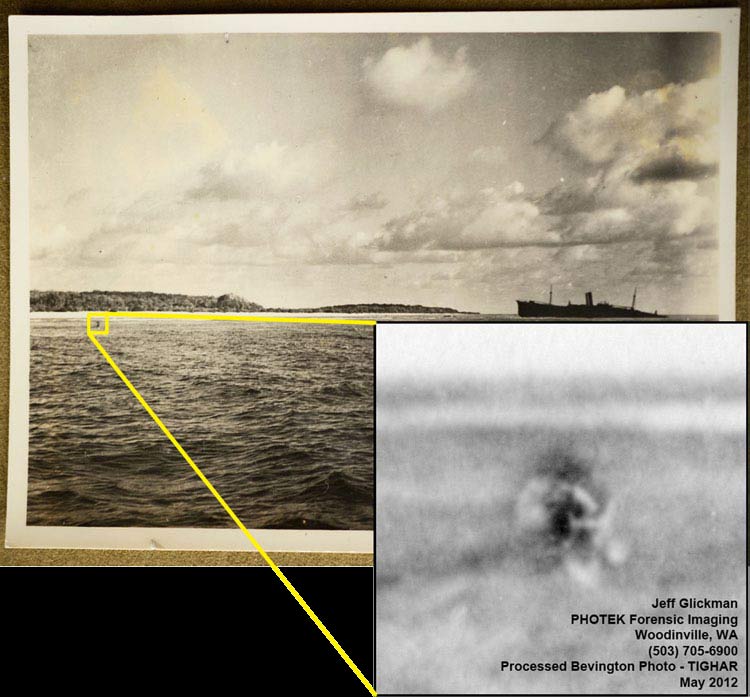

One of those locations matched a big clue — an object sticking out of the water in a British expedition photograph taken just months after Earhart's disappearance. Analysis by both TIGHAR and U.S. State Department experts suggested that the object fit the profile of Earhart's Lockheed Electra aircraft landing gear.

Making it all possible

Turning decades of sleuthing into a history-making payoff has required lots of outside help from the U.S. State Department and private companies. For instance, global delivery company FedEx has helped move 27,500 pounds of the expedition's robots and equipment by truck, ship and plane from the continental U.S. to Hawaii.

The robots and equipment will have moved about 22,000 miles by the end of the round trip — just shy of the distance covered by Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan before they vanished in their attempt to fly around the world.

"I'm sure for some people it would be a monumental move," said Virginia Albanese, CEO of FedEx Custom Critical. "For us at FedEx, this is what we do."

TIGHAR has raised almost all of the $2.2 million needed to make the expedition possible, but Gillespie vowed to go ahead with the full mission duration regardless. He pointed to Earhart as his inspiration — the aviator had to scramble for funding to repair her aircraft after it crashed during a first attempt to fly around the world.

"Future is mortgaged, but what else are futures for?" Earhart wired in a telegraph message.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.