500-Million-Year-Old 'Seaweed' Was Actually Home to Tiny Worms

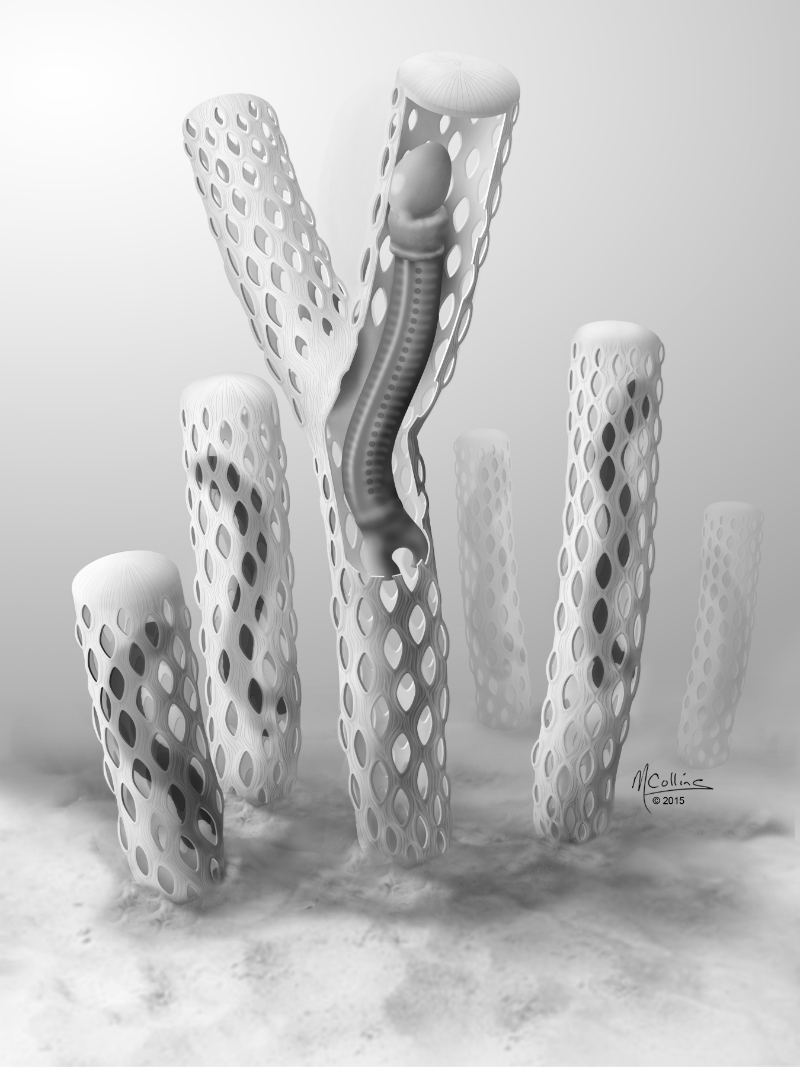

Some 500 million years ago, miniscule sea worms built and lived in ventilated tubes that stuck up from the ocean floor like tiny trees. And now scientists have discovered a fossil treasure trove of these curious homes.

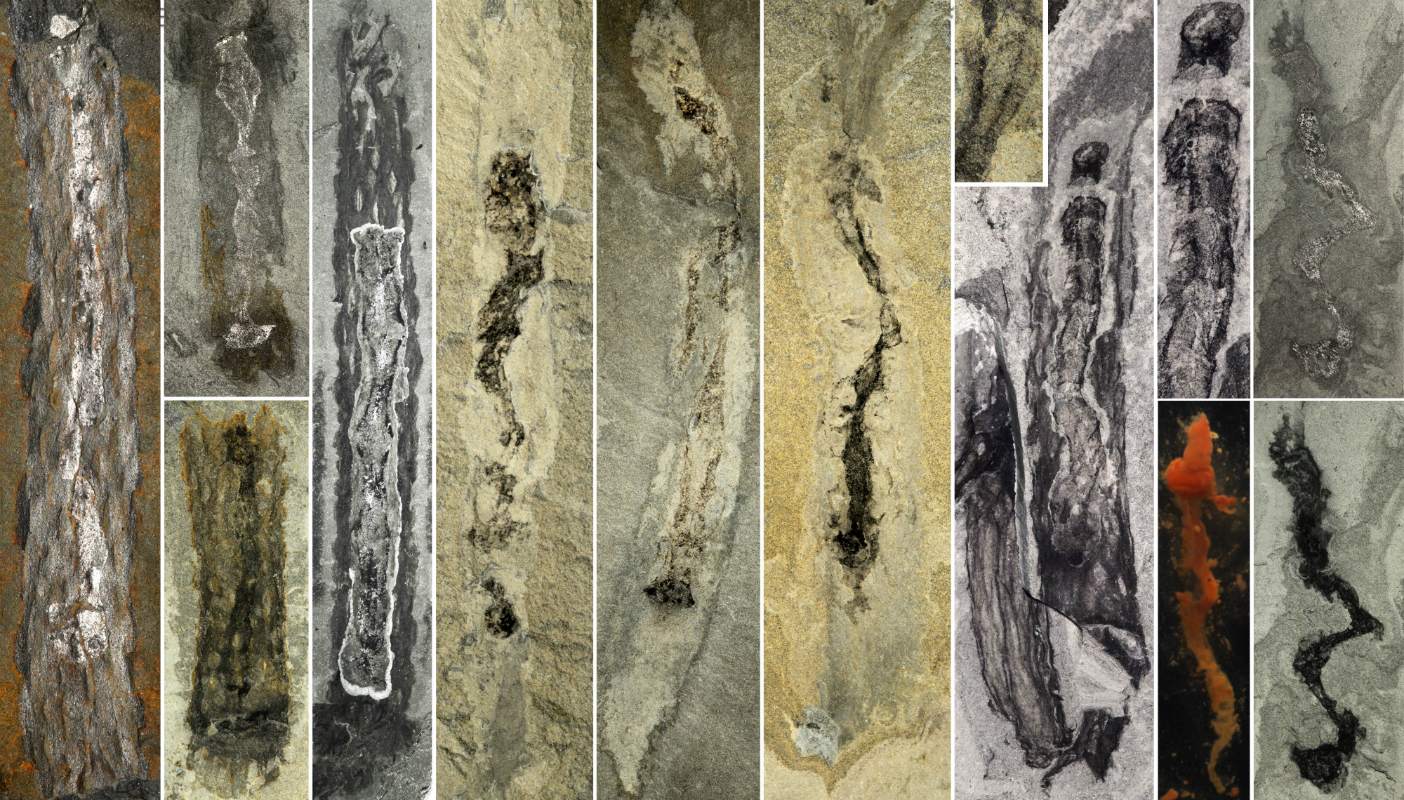

The fossilized finds, which included dozens of the latticework tubes with their miniature builders still inside, revealed that what scientists had previously identified as a type of seaweed called Margaretia actually comprised undersea dwellings.

The tubes also revealed a secluded worm life: It seems, these worms that built the tubes eventually sealed themselves inside to lead lonely lives in their one-room houses. [Cambrian Creatures Gallery: Photos of Primitive Sea Life]

Totally tubular

Researchers have known about the ancient worm Oesia (oh-EEZ-yah) since 1911, according to study co-author Simon Conway Morris, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. But fossil evidence was scarce, and the specimens described over 100 years ago "were not easy to interpret," Conway Morris told Live Science in an email.

The new fossil discoveries in Marble Canyon, a site in Kootenay National Park in British Columbia, Canada, changed all that.

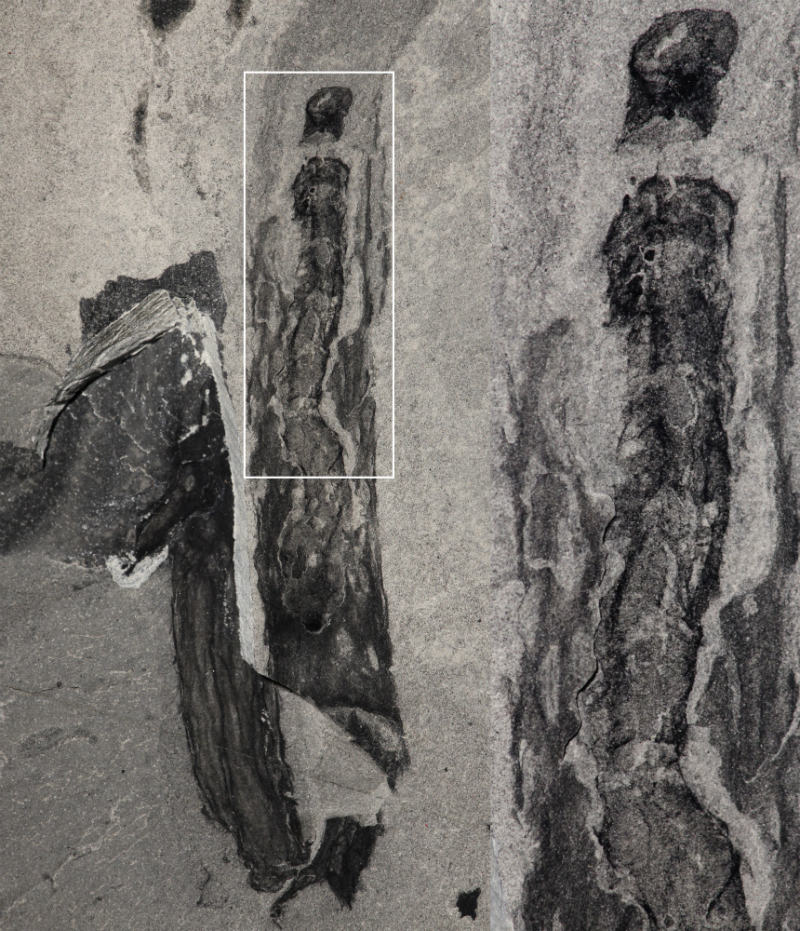

The new specimens "are far more abundant and better preserved, giving us unprecedented details of the animal's internal anatomy," study co-author Jean-Bernard Caron, a senior curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum and an associate professor at the University of Toronto, said in a statement.

From the new fossils, the researchers found that Oesia measured about 2.1 inches (53 millimeters) long and about 0.4 inches (10 mm) wide. It looked like contemporary acorn worms, having a long trunk topped with a collar and proboscis on one end. It also sported a grasping structure at its other end. Rows of curved slits along its body were used for filter feeding, the researchers noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As for the tubes, they were typically larger than the worms themselves, with some of the homes measuring 20 inches (50 centimeters) high, the researchers found. Conway Morris suggested that these structures were most likely made of collagen, similar to the ligaments in a person's Achilles' tendon. The tubes probably protected the worms from predators, he said.

Oesia likely had a specialized gland that produced strands of collagen, which could be "knitted" into the tube structure, leaving "windows" for water to pass through so the worm could feed, Conway Morris told Live Science. And horizontal extensions at the bottom could have anchored the tubes to the seafloor, he added.

Fossils showed only one worm per structure, suggesting that Oesia's tube-homes were single-occupancy, the researchers said in the study, published online July 6 in the journal BMC Biology.

Anatomical information provided by the fossils also helped the scientists fine-tune their placement of Oesia on the tree of life. They put it with hemichordates, a group of marine invertebrates closely related to echinoderms, the group that includes starfish and sea cucumbers.

And Oesia may be earliest example of this group found to date, Conway Morris said.

"Oesia fossils are pretty enigmatic — they are very rare, and until now we could not prove which group they belonged to," he said in a statement. "Now we know that they were primitive hemichordates — perhaps the most primitive of all."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.