'Letterlocked' Trove: X-Rays to Peer into Sealed 17th-Century Notes

For years, Jana Dambrogio, a conservator at MIT, has been studying the elaborate ways people used to fold and seal their letters to keep busybodies and spies from reading their secrets.

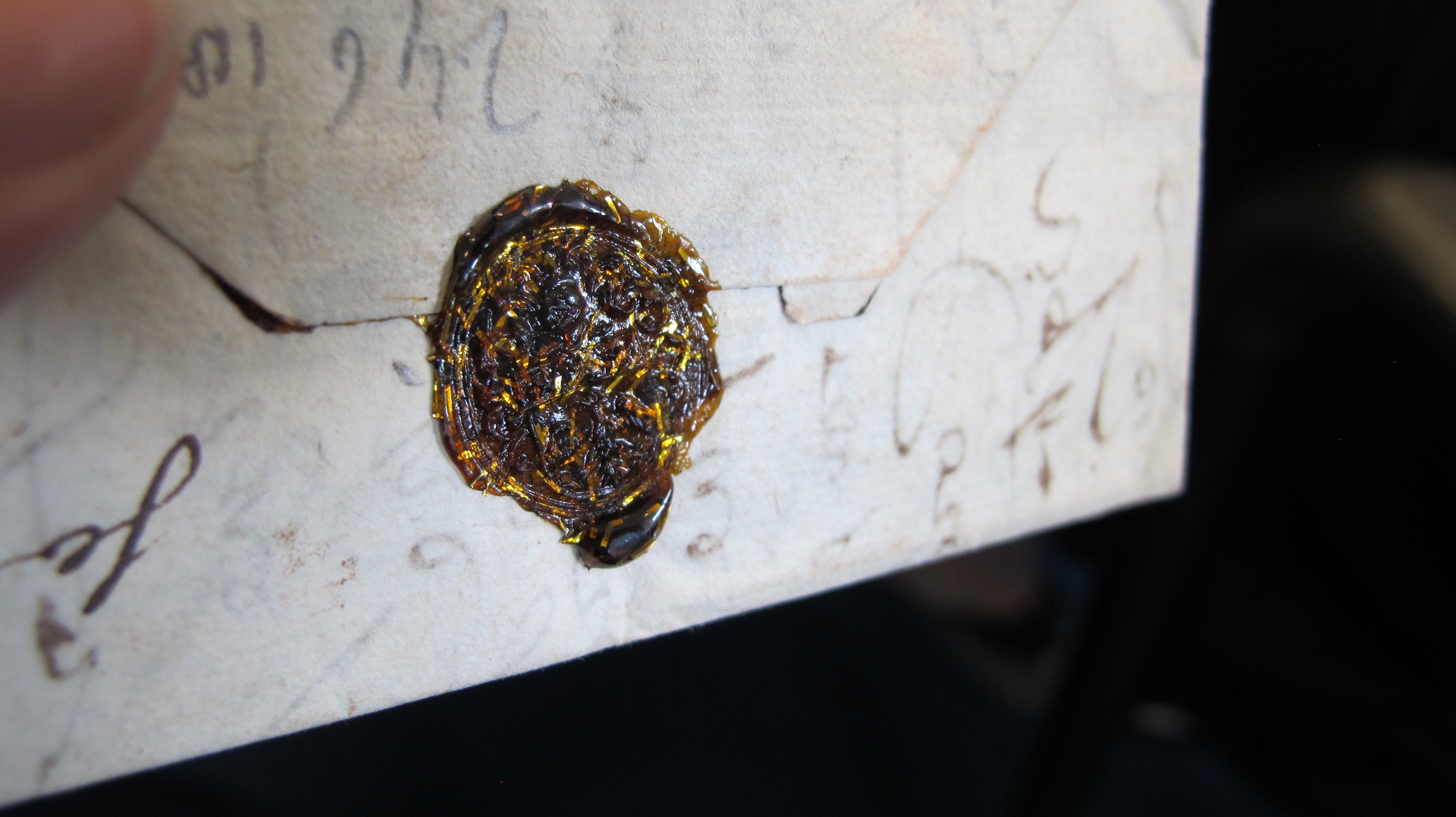

The way a paleontologist analyzes fossils to reconstruct extinct creatures, Dambrogio looks at the blobs of wax and the folding patterns on flat, already-opened letters in manuscript collections so that she can reverse-engineer "letterlocking" techniques. She had never held a historical, unopened locked letter in her hand until she got a call from her colleague, Daniel Starza Smith, at the University of Oxford.

"He asked me, 'What would you do if I told you there was a trunk with 600 unopened letters?'"Dambrogio said. "He had me at 'unopened.'" [See photos of the treasure trove of sealed 17th-century letters]

That trunk, which belonged to a 17th-century postmaster, had been sitting undisturbed in The Hague's Museum voor Communicatie since 1926. It was recently rediscovered and found to contain about 2,600 undelivered letters—600 of them unopened — from across Europe. Dambrogio, Smith and several other researchers are now collaborating on a new project to study the rare archive.

The letters, written in French, Spanish, Latin, Italian, Dutch and English, were once in the care of a postmaster named Simon de Brienne, who lived in The Hague, in the Netherlands. The recipients of these letters either could not be found or refused to pay the outstanding postage costs, so Brienne held onto the documents, hoping someone would eventually pay for them, according to a news release about the project.

Penned by aristocrats, wandering musicians and Huguenot exiles alike, the letters could offer a glimpse into the lives of Europeans in the Early Modern period.

"So many of the concerns expressed in these letters are the same as today: parents worried about their children, wives angry at delinquent husbands," Rebekah Ahrendt, a scholar at Yale University, said in a statement. Ahrendt discovered the trunk with her colleague, David van der Linden, a researcher at the University of Groningen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dambrogio has several instructional videos online that show different letterlocking techniques. (With names like "triangle-shaped paper lock with slit parallel to fore-edge," it's easy to see why these strategies are better explained in visuals than words.) She got to see the Brienne archive last summer, and already, she said she can tell there are a variety of structures that haven't been seen before. But, she won't get to unfold an original one herself.

"We could cut these things open but we're choosing not to," Dambrogio told Live Science. "It's a privilege to get to keep them shut."

These letters are like "little time capsules of information," Dambrogio explained, and the team wants to leave the original historic evidence for researchers of the future, who might eventually develop ways to study things like local pollution from analyzing the letters, or pull novel information from pieces of hair trapped inside a sealed letter.

Instead, as part of the current project, called Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered, the researchers will virtually unfold the unopened letters. They will use techniques like 3D X-ray microtomography to scan the letters and reconstruct the letterlocking strategies. They'll also use scans to detect the ink and reconstruct the text inside —all without ever breaking the wax seals. These same techniques have been used to virtually unroll and reconstruct famous manuscripts, such as texts buried in volcanic ash at Herculaneum and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The study of letterlocking is still in its infancy, but Dambrogiothinks it will bring a whole new layer of research to the understanding of historical manuscripts that scholars hadn't considered before. For example, some techniques that use floss might convey intimacy, while removable locks might be used in formal or ceremonial situations. She said she is looking forward to the team making connections between content and form, showing how a letterlocking folding format corresponds with the document's security levels or subject matter.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.