Hundreds of ancient papyrus scrolls that were buried nearly 2,000 years ago after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius could finally be read, thanks to a new technique.

The X-ray-based method can be used to decipher the charred, damaged texts that were found in the ancient town of Herculaneum without having to unroll them, which could damage them beyond repair, scientists say.

One problem with previous attempts to use X-rays to read the scrolls was that the ancient writers used a carbon-based material from smoke in their ink, said study co-author Vito Mocella, a physicist at the National Research Council in Naples, Italy.

"The papyri have been burnt, so there is not a huge difference between the paper and the ink," Mocella told Live Science. That made it impossible to decipher the words written in the documents.

If the new method works, it could be used to reveal the secrets of one of the few intact libraries from antiquity, the researchers said. [See How the New X-ray Method Works]

Buried in ash

Both the Roman city of Pompeii and the nearby, wealthy seaside town of Herculaneum were wiped out when Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, killing thousands of people and covering fine villas in ash and lava.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the 1750s, workers uncovered a library in a villa thought to be the home of a Roman statesman. The site, known as the Villa of the Papyri, contained nearly 2,000 ancient papyrus scrolls that had been charred by the volcanic heat.

Since then, historians have tried many ingenious (and some not-so-ingenious) methods for reading the damaged scrolls.

"They poured mercury on them, they soaked them in rosewater — all kinds of crazy stuff," said Jennifer Sheridan Moss, a papyrologist at Wayne State University in Detroit and the president of the American Society of Papyrologists.

From the few scrolls that could be unrolled and deciphered, historians determined that the library was filled mainly with writings on Epicurean philosophy — a school of thought that holds, among other things, that the goal of human life is happiness, characterized by the absence of pain and mental strife — and was part of the collection of a prolific writer named Philodemus.

"Most of what we know of Epicureanism is from these papyri," Mocella said.

Though some of the methods used to unroll the scrolls, such as a clever unrolling machine designed by a monk in the 1700s, were fairly successful, most wound up damaging the fragile documents.

Revealing secrets

Historians decided that the potential for damage was too great, and thus locked the remaining scrolls, still rolled up, in the National Library of Naples in Italy. A few years ago, researchers tried to read the scrolls without unrolling them, using X-ray tomography, which takes X-rays from multiple angles to recreate a 3D image of an object.

But this process is based on the fact that hard, dense materials absorb more X-rays than softer materials, and it didn't work for the scrolls because the smoke-based ink was too similar to the charred paper.

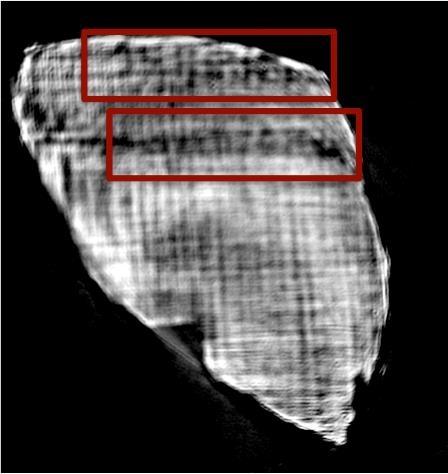

So the team looked to a similar technique, called X-ray phase-contrast tomography. Because the letters on the papyrus are slightly raised in height, the waves of X-rays that hit the letters would be reflected back with a slightly shifted phase, compared with the waves that hit the underlying material. By measuring this phase difference, the team was able to reproduce the shape of the letters inside the rolled scrolls.

So far, the team has analyzed six scrolls that were given to Napoleon Bonaparte as gifts and are now housed at the French Institute in Paris. They have deciphered some of the Greek letters and words written inside the rolled-up, burned, smushed scrolls.

Still, deciphering the words in the innermost layers was extremely challenging, the authors wrote in their paper.

Promising technique

The texts on the scrolls are unlikely to yield earth-shattering insights, given how many of the other scrolls have been deciphered, Moss said.

But the new technique holds promise for other burnt papyri as well, Moss said.

"Most people now believe there is a whole other library under there in that Villa of the Papyri," Moss told Live Science. That's because, in the Roman world, most libraries held all the Greek treatises in one section and all the Latin books in another, she said.

Archaeologists have a good idea of where the Latin library may be, but so far, they've found no trace of the Latin texts, in part because noxious gases released from the ground make the site difficult to excavate. But if they do find the hidden library, this new technique could become very useful there, Moss said.

"We could easily find more things that are in bad shape like this, and then the technology could be applied to them," Moss said.

The new technique was described today (Jan. 20) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.