Ancient Reptile with Bizarre Smile Kept Tooth Fairy Busy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

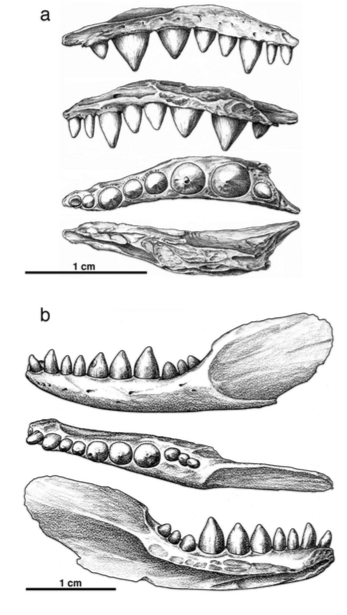

DALLAS — The large and bulbous teeth of an early reptile likely helped it crunch beetles and other hard-shelled invertebrates about 290 million years ago, a new study finds.

But the curious creature also lost teeth as it aged, giving it a less toothy smile in its senior years.

"Since we have so many specimens, we can actually see how the dentition changes throughout the life of this organism," said Robert Reisz, a distinguished professor of paleontology at the University of Toronto Mississauga, who presented the findings here at the 75th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference on Wednesday, Oct. 14. "Interestingly, the number of teeth is reduced in the larger, older animals because the individual teeth got bigger relative to the size of the animal." [Photos: Ancient Crocodile Relatives Roamed the Amazon]

Researchers discovered the newfound species at a limestone quarry near Richards Spur, Oklahoma. The quarry is teeming with fossils of ancient land-dwelling vertebrates, including small reptiles. But many of the fossils are fragmented — mostly an assortment of jaws and isolated bones, Reisz said.

In fact, researchers concluded in earlier studies that many of the fossils belonged to the species Euryodus primus, a four-legged amphibious creature. But when the researchers of the new study found more complete skulls and skeletons of the critter, they realized that the specimens "belong instead to a previously unrecognized and unusual" reptile, they wrote in the study, which is published in the October issue of the journal Naturwissenschaften.

They named it Opisthodontosaurus carrolli, derived from the Greek words opisthos (behind, rear) and odontos (tooth) — a reference to the animal's "conspicuously large tooth" toward the back of its lower jaw that is usually followed by two or three smaller ones, the researchers wrote. The species name honors Robert Carroll, who made many contributions to Paleozoic vertebrate paleontology, they said.

The newly named Opisthodontosaurus carrolli is a captorhinid, a group of lizardlike reptiles that had broad and strong skulls. Captorhinids were also part of the first large evolutionary burst of diversity among land-dwelling early reptiles, the researchers said in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers did a thorough anatomical study of the fossils. They noted that Opisthodontosaurus had a large coronoid process, a projection on the jaws that attaches to the muscle. It even looks "reminiscent of the mammalian" coronoid process, "but this animal is nearly 290 million years old," Reisz said. (One of the oldest mammals, Morganucadon, lived about 210 million years ago, according to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.)

Despite its intriguing teeth, Opisthodontosaurus actually had fewer of them compared with other captorhinids. But analyses show that Opisthodontosaurus' teeth and jaws had similarities with other four-legged lizardlike animals called recumbirostran microsaurs. This suggests their dental anatomy was convergent, or that it evolved the same way in separate species.

These Permian period creatures may have evolved to sport such interesting dentition because they ate similar prey — "arthropods tougher than those normally subdued by simple piercing dentition," the researchers said.

This is consistent with the fossil record of arthropods, which emerged during the Late Carboniferous (the period before the Permian) and the Early Permian, the researchers said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus