Photos: Ancient Crocodile Relatives Roamed the Amazon

The fossilized remains of seven species of crocodile relatives were found along the banks of the Amazon River in Peru. These prehistoric reptiles lived in South America at a time when the Amazon River basin contained swamps, rivers and lakes, as well as a multitude of clams. But when tectonic forces created the Amazon River, the swamps and the clams largely disappeared. It's possible that, in turn, these crocodile relatives changed their diets and body shapes, the researchers of a new study say. [Read the full story on the prehistoric crocodile relatives]

Shovel mouth

A model of the 13-million-year-old Gnatusuchus pebasensis, a crocodylian with a short face and rounded teeth that may have shoveled through the mud at the bottom of lakes and swamps to find prey, such as clams and other mollusks. A crocodylian is an order that includes crocodiles, alligators, caimans and gharials. (Image credit: Model by Kevin Montalbán-Rivera. © Aldo Benites-Palomino)

Wetland snacks

This illustration shows the massive wetlands that once covered the Amazon River basin about 13 million years ago during the late middle Miocene. Three newly discovered species of crocodylians, including Kuttanacaiman iquitosensis (left), Caiman wannlangstoni (right) and Gnatusuchus pebasensis (bottom), look for clams, which they could likely scoop up with their mouths and crunch with their peglike teeth. (Image credit: © Javier Herbozo)

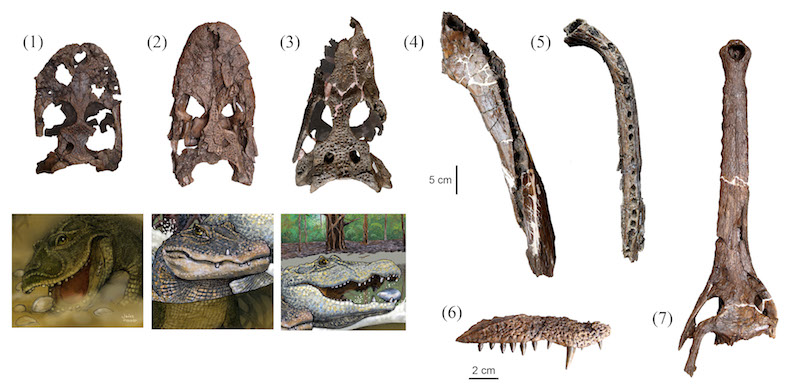

Croc fossils

Excavated fossils from Peru show that seven species of crocodylian lived together in the same place at relatively the same time. The skulls and jaws, shown above, are extremely diverse, the researchers said. They include (1) Gnatusuchus pebasensis, (2) Kuttanacaiman iquitosensis, (3) Caiman wannlangstoni, (4) Purussaurus neivensis, (5) Mourasuchus atopus, (6) Pebas Paleosuchus, and (7) Pebas gavialoid. (Image credit: Reconstructions by Javier Herbozo. © Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dry season

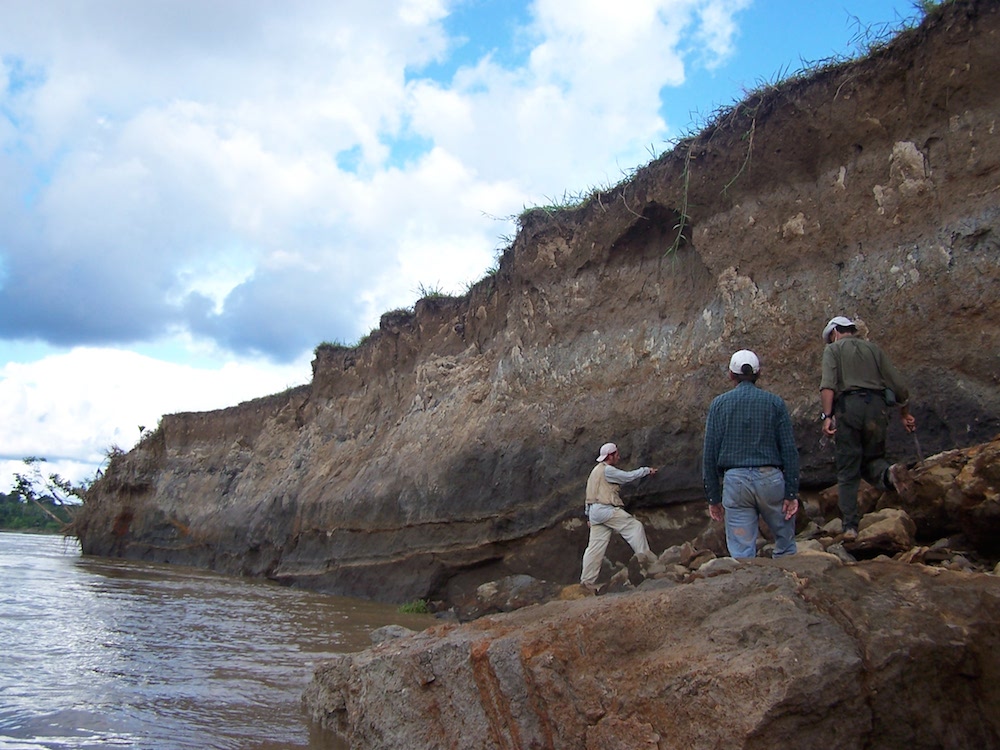

For more than a decade, researchers have traveled to Peru during the Amazon's dry season in July and August. Here, they scale an embankment for fossils when the Amazon River was at low levels. (Image credit: © Anjali Goswami)

Rock of ages

Researchers found all seven of the crocodylians in the same layer and the same place, which measured only about 215 square feet (20 square meters).

"It's a very small area full of bones," said the study's lead author, Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi, a graduate student at the University of Montpellier, in France, and chief of the paleontology department at the National University of San Marcos' Museum of Natural History in Lima, Peru. (Image credit: © Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi)

Ancient skull

One of the newly discovered species (Gnatusuchus pebasensis) is shown here in the earth before the researchers excavated it. Today's crocodylians have longer snouts and sharper teeth, which help them to catch fish and other aquatic animals, unlike this distant relative, which likely used its peglike teeth to crush clams. (© Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi)

Museum collection

All of the fossils found during the study are being stored at the Museum of Natural History in Peru.

"This kind of research promotes paleontology in Peru," Salas-Gismondi told Live Science. (Image credit: © Bruce Shockey)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus