Dino Down Under Sported Claws the Size of Kitchen Knives

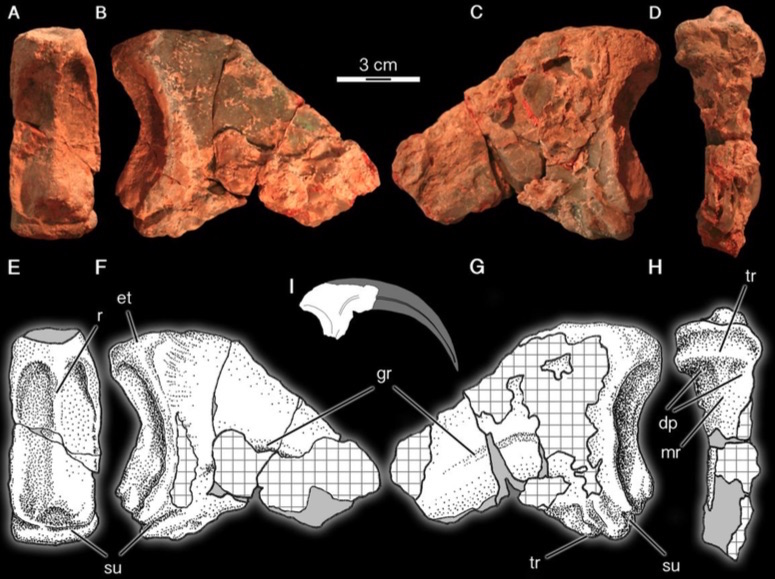

The largest meat-eating dinosaur ever discovered in Australia had sickle-shaped claws the size of chef's knives, a daunting feature that likely made up for its fairly delicate jaws and small teeth, a new study finds.

The dinosaur's 10-inch-long (25 centimeters) claws likely helped it hunt, said study lead researcher Phil Bell, a lecturer of paleontology at the University of New England in Australia.

"They didn't have skulls like T. rex, which could crush bones with their incredible bite," Bell told Live Science. "Instead, they probably used their hands and massive claws — a bit like a raptor — to bring down their prey." [Photos: 7-Year-Old Boy Discovers T. Rex Cousin]

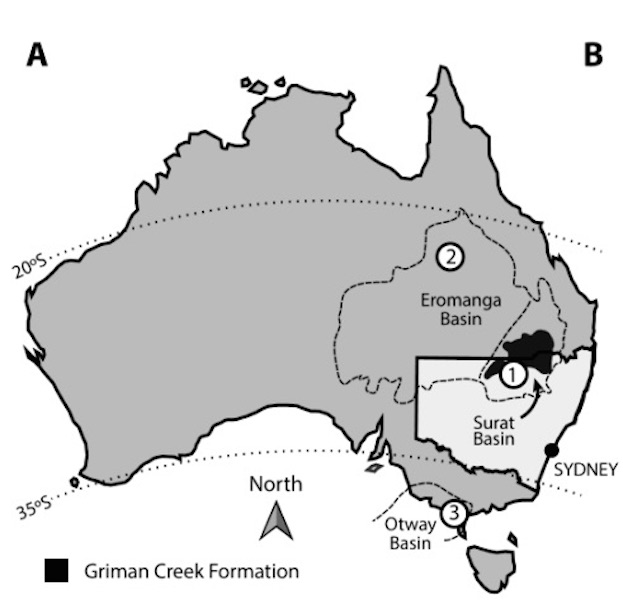

The newfound claw-wielding dinosaur lived about 110 million years ago, during the mid-Cretaceous, and likely measured about 20 feet (6 meters) long. Miners discovered and excavated the partial skeleton in the 1990s in the opal fields near the town of Lightning Ridge, located in New South Wales in eastern Australia. The fossils, most of them a bluish hue, thanks to the opals, were donated to the Australian Opal Centre in 2005, and remained on display until Bell and his colleagues decided to study them.

Unfortunately, the miners may have missed or destroyed some of the fossils, and fresh breaks on the bones suggest they were damaged during excavation, the researchers said. Still, the finding is the second most-complete skeleton of a theropod (a group of bipedal, mostly meat-eating dinosaurs) from Australia, Bell said.

The researchers chose not to name the new species just yet — primarily because the skeleton is incomplete — but are calling it "lightning claw" for now in honor of its location and impressively sized claws.

Origin dilemma

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists are sure of one thing: Lightning claw is a megaraptorid, an enigmatic group of theropod dinosaurs that sported long claws and lived on the southern supercontinent Gondwana. Researchers have found other remains of megaraptorids in South America and Australia.

However, they are unsure where megaraptorids sit in the theropod family tree. Some researchers suspect the group belongs to the tyrannosaur branch (the dinosaurs that evolved into birds), and others say it's more closely related to primitive theropods, such as Allosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus, the researchers said.

The authors didn't use lightning claw to help solve the mystery because "there's only so much you can answer at one time," Bell said. "The issue of where megaraptorids sit in the great family tree of theropoda is a much bigger problem than trying to identify a single species, for example."

But the finding does provide clues about the origin of megaraptorids. Lightning claw predates the oldest known megaraptorid found in Australia (Australovenator) by 10 million years. Moreover, Australia is largely known as a fossil "dark continent" because it has divulged few dinosaur fossils compared to the other continents (with the exception of Antarctica).

Despite Australia's dearth of uncovered dinosaur fossils, the bluish specimen suggests that some megaraptorids may have originated Down Under. [Paleo-Art: Dinosaurs Come to Life in Stunning Illustrations]

"Most other megaraptorids come from Argentina, so it seemed to make sense that megaraptorids in Australia must have made their way here from South America," Bell said. "When we ran our computer analysis, no matter how we looked at it, our new guy seemed to switch that idea on its head."

"It's fantastic to see something that's new, identifiable and actually can inform us about dinosaur evolution and biogeography," said Thomas Carr, an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin and a vertebrate paleontologist, who was not involved in the study. "It helps complete that large mosaic of our knowledge of the history of life on earth. It's another tile — an important one."

The findings were published online Sept. 5 in the journal Gondwana Research.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.