Cartwheeling Spider, Corpse-Hoarding Wasp Among Bizarre New Species

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

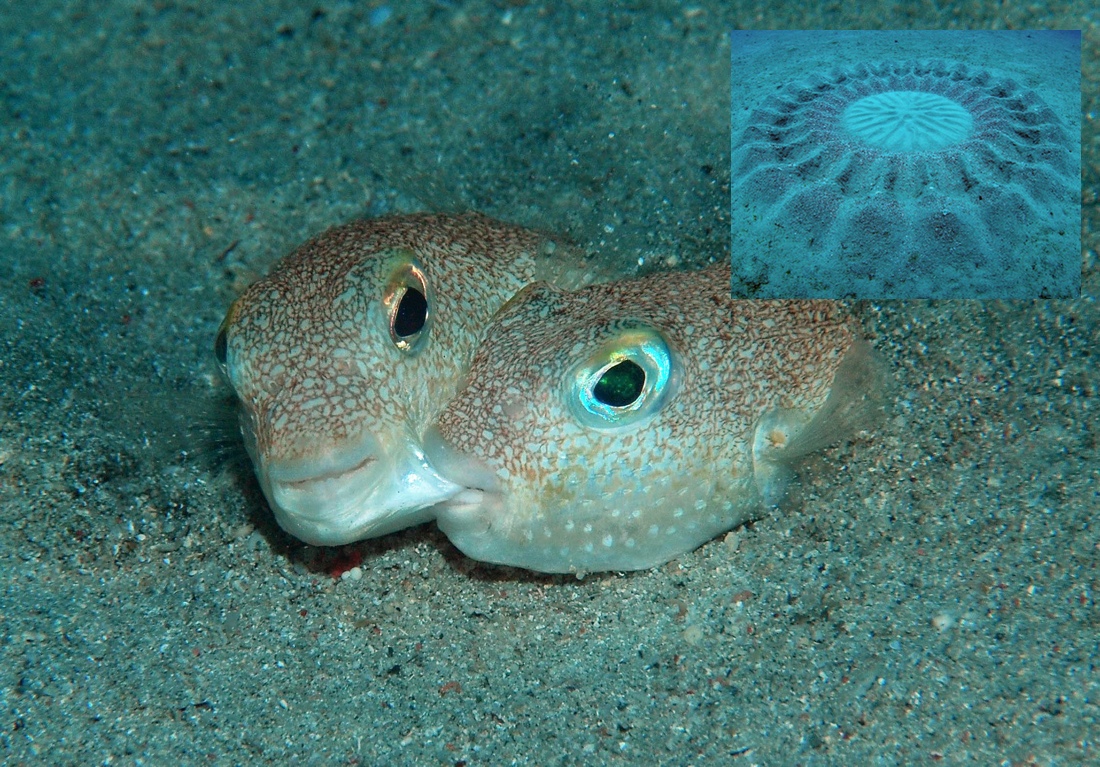

A morbidly maternal wasp, a crop-circle-creating pufferfish and an acrobatic arachnid are among the bizarre and awe-inspiring new species named in 2014, according to a new ranking.

Some 18,000 species were newly named and identified last year — a tiny fraction of the estimated 10 million or so species yet to be discovered on Earth. (Scientists have identified and described about 2 million species thus far.) To draw attention to the planet's unexplored biodiversity, scientists at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry's International Institute for Species Exploration (IISE) picked just 10 of the 18,000 species to highlight.

Among them is the creepy "bone house wasp," Deuteragenia ossarium. Females of this species create nursery chambers for their eggs in hollow plant stems, stocking each chamber with a dead spider so the young have sustenance upon hatching. Then, in a truly bizarre twist, the wasp moms build a final antechamber to their nests, filling it with ant corpses. Researchers suspect the dead ants give off scents that keep predators away from the vulnerable wasp hatchlings. [See Photos of the Top 10 New Species]

Wild animals and weird plants

Other 2014 honorees include an Indonesian frog, Limnonectes larvaepartus, which gives birth to live tadpoles — the only frog known to reproduce in that way. (Most frogs lay eggs, and a few give live birth to miniature frogs.) And then there's Cebrennus rechenbergi, a spider of the Moroccan desert that cartwheels across the sandy dunes when threatened. Even more astounding is the behavior of Japan's newly discovered pufferfish, Torquigener albomaculosus. Males of the species create elaborate circular designs in the sand on the seafloor to attract mates. For decades, the origin of these undersea "crop circles" was a mystery.

Plants are also represented among the newly discovered species. Tillandsia religiosa is a red-and-green bromeliad plant long used to decorate alters during the Christmas season in Mexico. Only in the past few years did scientists take a closer look and realize no one had ever bothered to give the plant a scientific name. And the parasitic plant Balanophora coralliformis was discovered and declared endangered in the same breath; the coral-like plant grows only on the southwestern slopes of one mountain on Luzon Island, in the Philippines.

Race against extinction

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The list highlights biodiversity at a time when scientists estimate that species are going extinct far faster than humans can discover them.

"We have only begun to explore the astonishing origin, history and diversity of life," Quentin Wheeler, founding director of the IISE and president of the College of Environmental Science and Forestry, said in a statement.

Even animals that science has named and classified can easily slip away. The northern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni), survives only in captivity; just five individuals are left on Earth. And the red-crested tree rat (Santamartamys rufodorsalis) was thought extinct until biologists working in Colombia stumbled across one in 2011; the animal remains on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's list of the 100 most-threatened species on the planet. The IUCN also lists animals and plants that, like the northern white rhino, are extinct in the wild and survive only in zoos. Among them are the colorful red-and-blue Socorro dove (Zenaida graysoni), which has not been seen in the wild since 1972; the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah), which vanished from its native Africa in the past 15 years; and the Hawaiian crow (Corvus hawaiiensis), which disappeared in the wild in 2002.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus