LA's Island Playground Could Trigger Tsunamis

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

PASADENA, Calif. — Landslides coming off Catalina Island's steep slopes could send tsunamis racing toward popular Los Angeles and Orange County beaches with just a few minutes of warning, geoscientists said on April 23 here at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America.

Researchers discovered chaotic deposits that are characteristic of landslides while probing underwater rocks offshore Catalina Island. Seismic waves provide images of underground sediment and rock layers in a manner similar to medical CT scanners that search for cancer and broken bones. [Waves of Destruction: History's Biggest Tsunamis]

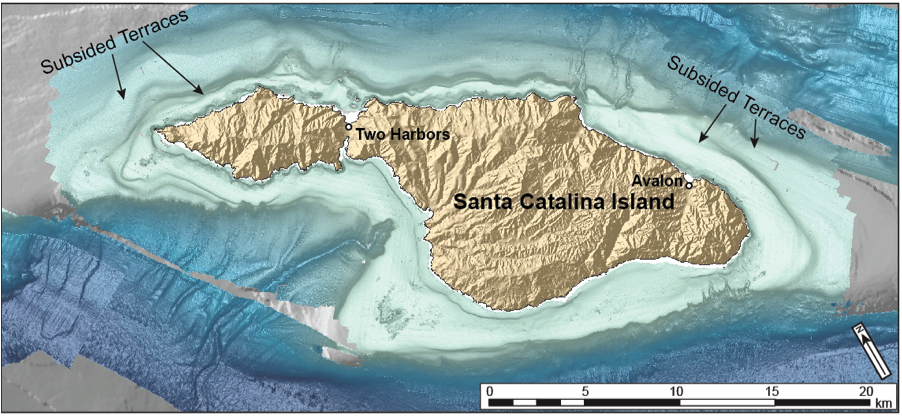

The landslides were buried underwater because Catalina Island is sinking, said lead study author Chris Castillo, a Stanford University graduate student. The remnants of old beaches have dropped beneath the waves as the island descends, creating a stair-stepped series of nine terraces.

"Catalina is rare," Castillo told Live Science. "We knew there was evidence of subsidence, but it's the only [Southern California] island that has these submerged beaches."

Catalina's nearest neighbor to the south, San Clemente Island, has ancient beaches that sit about 1,800 feet (550 meters) above sea level.

Castillo does not yet know how fast Catalina Island is sinking. The oldest terrace is about 720 feet (220 m) below current sea level. The island is also tilting as it descends, which increases the landslide threat by destabilizing the steep coastal slopes, he added.

However, Castillo will soon get a better handle on the rate of sinking by matching the beach levels to well-known sea level changes during the past 1 million years. The research team plans to recover fossils from the terraces this summer, which will help connect Catalina's terraces to these past sea level events, he said. Currently, the researchers think the island is sagging by about 1 foot (30 centimeters) every 1,000 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Disaster planners have already recognized that California faces a rare but plausible tsunami risk from its iconic coastline. Major offshore fault lines have triggered small tidal waves during historic earthquakes. However, when these faults slip, the seafloor typically moves horizontally, without launching huge waves.

Instead, California's biggest local risk of deadly tsunamis comes from unpredictable underwater landslides. These avalanches shove seawater aside, setting off tsunamis. And in the new study, geologists found evidence of such enormous submarine landslides offshore Catalina Island.

Although tidal waves from submarine landslides only threaten local coastlines, the waves can kill. A submarine landslide triggered tsunamis that killed 2,200 people in Papua New Guinea in 1998.

"Landslides can have a big impact in a small area, and you don't get a lot of warning," said geophysicist Stephanie Ross, project leader for tsunami hazard scenarios for the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California. Ross was not involved in the study.

California's tsunami flooding maps account for such worst-case scenarios, said Rick Wilson, a California Geological Survey senior engineering geologist.

But new geologic surveys are finding evidence that could heighten the tsunami risk. For instance, two earthquake faults offshore Ventura, between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles, shove the seafloor upward during quakes, according to research presented here Wednesday (April 22). This style of movement can generate tsunamis.

The two faults — the Pitas Point fault and the Red Mountain fault — could potentially unleash a magnitude-7 earthquake, said Kenny Ryan, a University of California, Riverside, graduate student. For the study, Ryan modeled tsunamis created by faults. He found that the waves turn counterclockwise toward the towns of Ventura and Oxnard once they hit deep water. "Tsunamis travel at different speeds depending on water depth," Ryan said.

Scientists are unsure how often tsunamis of any kind hit Southern California's coastline because there are few sand deposits onshore left by waves. The biggest study of tsunami deposits to date, published in 2014, looked for prehistoric tsunamis in 20 coastal locations and struck out at all but two.

So far, although the state has considered the new studies, its tsunami maps haven't needed revising, Wilson told Live Science. "These are very low-probability events," Wilson said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus