How Smart Homes Could Power the Future

Editor's Note: Each Wednesday LiveScience examines the viability of emerging energy technologies — the power of the future.

BARCELONA, Spain — As much as 75 percent of a home's heat escapes through the roof and walls. A new European initiative plans to design homes that are much smarter about energy use.

A typical U.S. or European household consumes around 13,000 kilowatt-hours of energy per year on space heating. A number of building designs have been put forward that cut this and other home energy use to nearly zero, but only a few of the houses have been built.

"Homes of the future have never really made it in the market," said Rüdiger Iden from the German chemical company BASF AG.

The Smart Energy Home initiative hopes to avoid these market failures by taking a broader approach that does not rely on expensive stand-alone technologies. Iden and others presented some of the initiative's plans here July 20 at the Euroscience Open Forum (ESOF) 2008.

As part of the initiative, BASF and a number of other companies, including Spanish construction firm Acciona, recently formed a consortium to bring energy-saving technologies — such as insulation, home sensors and co-generation — to market. They have plans to build at least six demo homes in various European cities by the end of 2009.

Passive house

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The exact configuration and look of future smart energy homes is still not completely decided. They will likely have a lot in common with "passive" houses.

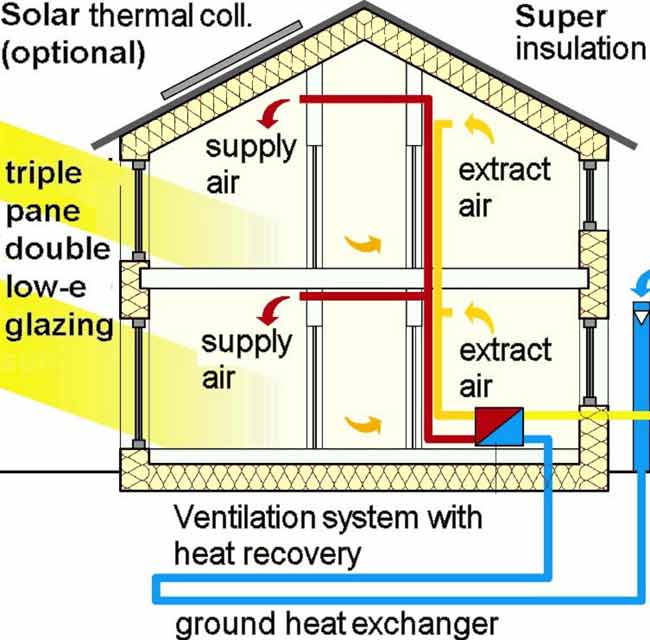

First built in Sweden, passive houses use a high-standard of insulation and air-tight construction. Incoming air is pre-heated by underground ducts that exchange heat with the soil, and windows and walls are carefully placed to maximize the use of sunlight.

By retaining its own heat, a passive house requires no more than 15 kilowatt-hours per meter-squared (1.5 kilowatt-hours per square foot) of external heating per year, which is about 10 times less than the current European average.

Passive houses cost roughly 20 percent more to build than other houses, said Fabrizio Cavani of the University of Bologna in Italy. He thinks they will remain a small niche of the market until the price drops to within 10 percent the cost of normal houses.

"The main resistance to everything is the cost," Cavani said at the ESOF meeting.

The Smart Energy Home initiative aims to incorporate existing technologies into a more marketable and cost-effective package.

Bottle up the heat

One of the main objectives will be improving insulation, as this is an easy way to reduce energy consumption.

Many homes have old insulation that was not made to last more than a few decades, said Sven Mönnig from BASF. Water condensation from a leaky roof, for example, can greatly reduce how effective insulation is at trapping heat.

Insulation has improved with foams that can be sprayed into every nook and cranny of the attic and walls. There are also so-called phase change materials that melt during the day to absorb more heat and then refreeze at night to release their stored heat.

Putting up new insulation typically costs around $5 per square foot, according to Mönnig, but the energy savings can pay back the initial cost in less than 10 years.

"Insulation pays off if you are a smart user or not," Iden said.

Globally, insulation improvements could annually save more than $100 billion, according to a 2007 report in the McKinsey Quarterly. And this would come with a reduction in more than a billion tons of CO2 emissions per year.

How smart?

Besides insulation, there are some innovative ideas for making houses more efficient.

Sensors can be installed that could tell when a person comes into a room (or even anticipate their arrival), thereby only heating and lighting the room when they are there. Cavani said that these types of automation technologies could cut energy consumption in half.

Another important innovation would be a co-generation system that makes both electricity and heat inside the house. This might be based on fuel cells that use ethanol, or micro-turbines that run off of natural gas.

Because co-generation uses waste heat from electricity generation, it can reduce total energy use in the home by 30 percent, Cavani said.

The question is: will the efficiencies of these smart homes be enough to seduce people to invest in them?

"The 'smartness' of people is growing with economic pressures from high-energy costs," said Laszlo Bax, a Smart Energy Home consultant.

- Innovations: Ideas and Technologies of the Future

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus