El Niño Can Predict Tornado Season's Severity

This year's El Niño may not only bring a bit of drought relief to parched Western states, but also could deliver a quiet tornado season, a new study finds.

Much of the southeastern United States faces a lower risk of tornadoes during El Niño years, the new research shows. The effects are strongest in Oklahoma, Arkansas and northern Texas. Damaging hail is also less likely during a strong El Niño, researchers report today (March 16) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"The cool thing is, you can actually forecast what the spring tornado season will be like," said lead study author John Allen, a severe weather climatologist at Columbia University's International Research Institute for Climate and Society in Palisades, New York. [The Top 5 Deadliest Tornado Years in U.S. History]

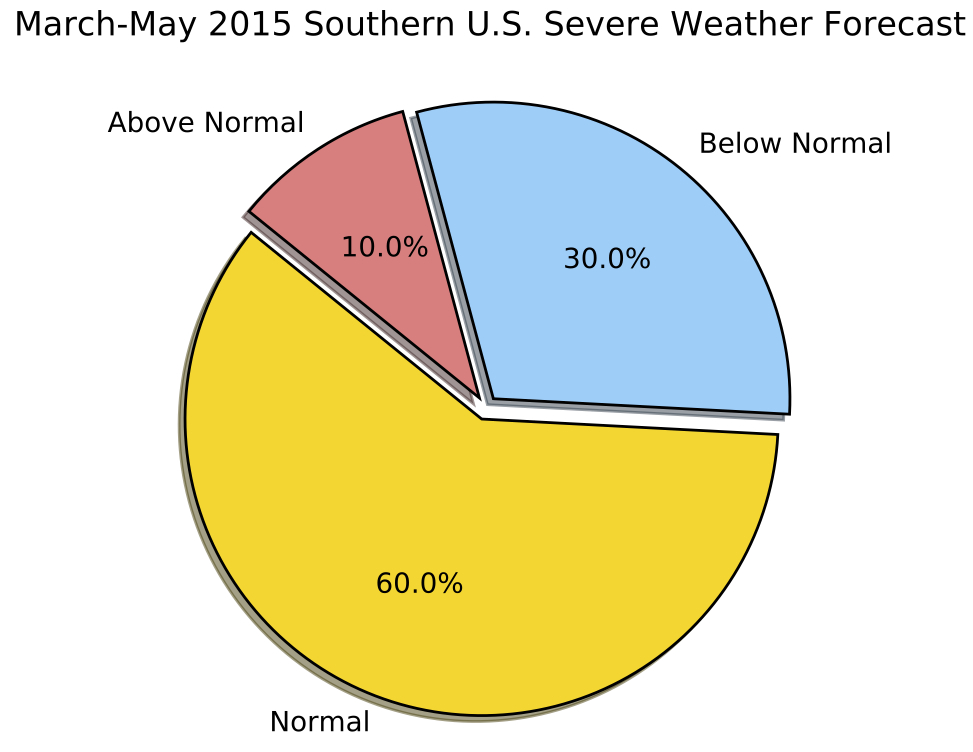

The team's experimental forecast for this March, April and June calls for a slightly lower risk of tornadoes due to this year's El Niño. There is a 60 percent chance of an average tornado year, a 30 percent chance of a below-normal year and a 10 percent chance of an above-average number of tornadoes, the researchers said. However, even a quiet year can see deadly twisters strike in the United States, Allen said. In 2013, a relatively quiet tornado year, a late May tornado outbreak killed dozens in central Oklahoma.

Tornado forecasts

Allen and his colleagues are part of a group of scientists who intend to start issuing seasonal tornado forecasts that are similar to the hurricane and seasonal outlooks issued by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The experts have been meeting yearly since 2012 to advance the science of forecasting tornadoes.

Currently, the National Weather Service's Storm Prediction Center issues tornado outlooks up to eight days in advance. In contrast, hurricane outlooks come several months ahead of the summer storm season.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, though the Columbia University research team plans to issue its own forecast as soon as next year, optimistically, an official forecast is at least five years away, said Ashton Simpson Cook, a meteorologist at the Storm Prediction Center who was not involved in the research. "We've already started on it, [but] we're in the beginning phase," he told Live Science.

The new findings are based on a comparison of weather records during El Niño years versus La Niña years. The authors did not use historical tornado records, which are fraught with reporting biases. Instead, they analyzed the environmental conditions that favor severe weather, such as temperature, atmospheric moisture and wind shear, which is different wind directions and speeds at different elevations above the surface. Then, the team created a forecasting formula that linked wintertime El Niño-La Niña conditions to the probability of severe storm activity in the following months.

"This is a great study," Cook said. "It's the next step in assessing the role of ENSO [El Niño] on severe weather, not just tornadoes."

Warm ocean, few tornadoes

The El Niño-La Niña cycle, or ENSO, is a natural climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean. During an El Niño, warm sea surface temperatures spread across the tropics. In a La Niña year, the opposite happens: Cool sea surface temperatures dominate in the eastern tropical Pacific. These temperature shifts have a ripple effect on wind patterns around the world, which, in turn, affects where storms form. [Fishy Rain to Fire Whirlwinds: The World's Weirdest Weather]

NOAA declared El Niño’s arrival last week, after Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures crossed a warm threshold and wind patterns shifted in response.

So far, the 2015 tornado season is off to a slow start, with 28 tornados reported, according to the Storm Prediction Center. However, Allen said the cold weather across the eastern United States likely had a stronger effect than El Niño conditions on suppressing tornadoes so far this winter.

In an El Niño year, the jet stream is more southerly, which tamps down the wind patterns that generate severe storms. (For instance, the southerly flow brings cool, dry air from the plains and Canada.) The weather patterns that form twisters and hail decreased by 25 to 50 percent during an El Niño, the study reported.

During a La Niña year, the jet stream across North America shifts to the North, which favors more tornadoes in the Southeast. This brings warm, moist air into Tornado Alley, the twister-prone regions of the United States. Tornado and hail activity doubled across Oklahoma, Arkansas and northern Texas during strong La Niña years, the researchers reported. The opposite pattern is seen in the Gulf Coast and Florida panhandle, with an increase in tornado activity during El Niño and a drop during La Niña years, the researchers also noted.

"There is a geographical dependence, which explains why it might be hard to untangle the impact if you were to just look at the total number of tornadoes [each year] in the U.S.," said study co-author Michael Tippett, a climate scientist at Columbia University.

Direct observations from earlier studies agree with the findings. For example, there were spikes in tornado activity during strong La Niña years, such as in 1999 and 2011. Strong El Niño years brought a drop in tornados, in 1969 and 1988.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus