Greenland's Ice Loss Now Comes from Surface

SAN FRANCISCO — Greenland's disappearing ice shifted gears in the past decade, switching from shrinking glaciers to surface melting, researchers reported here last week at the American Geophysical Union's annual meeting.

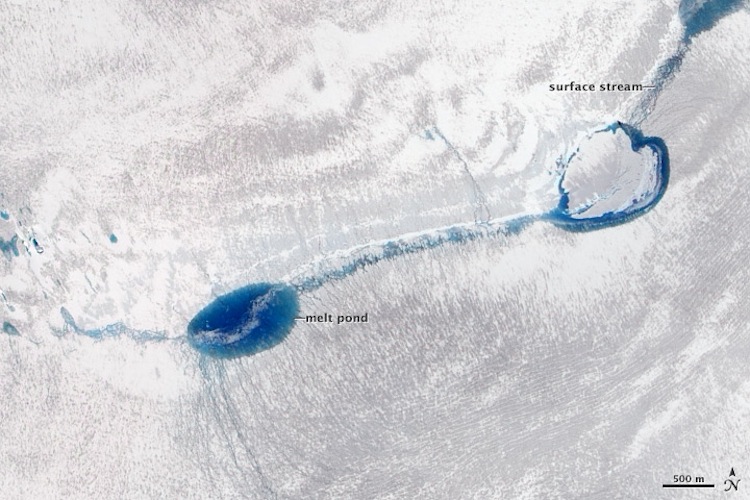

Instead of losing ice where massive glaciers meet the sea, Greenland now sends meltwater rushing into the ocean via a vast network of lakes and rivers, according to several studies. The results do not mean that glaciers have stopped their speedy flow, only that surface melting now exerts a more powerful influence on ice loss, researchers said.

"We no longer see giant icebergs calving" from glaciers, releasing ice into the sea, said Lora Koenig, a glaciologist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, who led one of the new studies. "The majority of water is coming from surface melt." [Photos: Under the Greenland Ice Sheet]

Koenig discovered that lakes in west Greenland now stay liquid through the frigid winter, as long as an insulating snow blanket keeps the water warm. These lakes get a head start on melting the next summer. "Water is not a good thing to have persisting year-round," Koenig said Dec. 15 at a news conference. "What this water is really doing is priming the pump [for melting] for the next season."

The meltwater boosts sea levels, which are projected to rise by 1 to 4 feet (0.3 to 1.2 meters) by 2100, according to the National Climate Assessment. Water that percolates beneath the ice sheet can also lubricate the underside of Greenland's glaciers, speeding up ice flow. But researchers are still figuring out where all of this new surface meltwater will end up.

"The water is what we have to follow," said Vena Chu, a hydrologist and graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Follow the water

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, each summer, a vast network of rivers appears in Greenland, channeling meltwater off the ice surface. Researchers said they want to know how much water refreezes in place, how much ends up under the ice sheet and how much flows out to sea. By tracking west Greenland's rivers on satellite images, Chu discovered that the river water all disappears into moulins — deep cracks that steeply plunge into the ice, she reported at the meeting.

"Now we need to know if the water gets stuck in there or if it comes straight out [to the ocean]," Chu said.

The growing flood of surface runoff has also transformed snow layers that blanket the ice sheet, researchers reported Dec. 16. Typically, the top of the ice sheet is blanketed by partially frozen, old snow called firn, which can suck up summer meltwater like a sponge. But 12 years of heavy summer melts have overwhelmed the firn's capacity in southwest Greenland, said Mike MacFerrin, a glaciologist and graduate student at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

The waterlogged snow is now frozen solid in many places, with ice more than 15 feet (4.6 m) thick just below the surface, he said. Now, summer meltwater streams over the ice instead of sinking into the snow. In 2012, this triggered record flooding during a huge melt event in Greenland, said MacFerrin, who led the study.

However, in other regions, Greenland's old snow still stockpiles huge amounts of water. Rick Forster, a glaciologist at the University of Utah, has uncovered additional evidence of a shallow aquifer of liquid water in southern and western Greenland. In 2013, Forster reported that parts of Greenland's snow firn hold an estimated 100 billion gallons of water through the winter months in the southeast.

From sea to surface

Koenig said global warming has triggered the shift to surface melting, which took place between 2006 and 2009. Temperatures in the Arctic are rising twice as quickly than at lower latitudes, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's annual "Arctic Report Card."

Greenland's glaciers have responded quickly to changing temperatures in the past, said Anders Bjork, a researcher at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

Using historical photographs from Danish aerial surveys of Greenland, Bjork mapped out the advance and retreat of glaciers that occurred when temperatures climbed between the years 1900 and 1930. The retreat was more rapid than has been seen in the last 15 years, he said.

Though the past century of change appears remarkably rapid, overall, the Greenland Ice Sheet is more resilient than most people assume, said glaciologist Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, head of the University of Copenhagen's Center for Ice and Climate. The ice has survived 900,000 years of climate change, and it would take a temperature rise of 18 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) before a forest starts to grow again in Greenland, she reported here Dec. 17.

"We are just seeing the beginning of a reaction to the warming," Dahl-Jensen said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.