Strange Fossil Shows How Life Responded After Mass Extinction

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

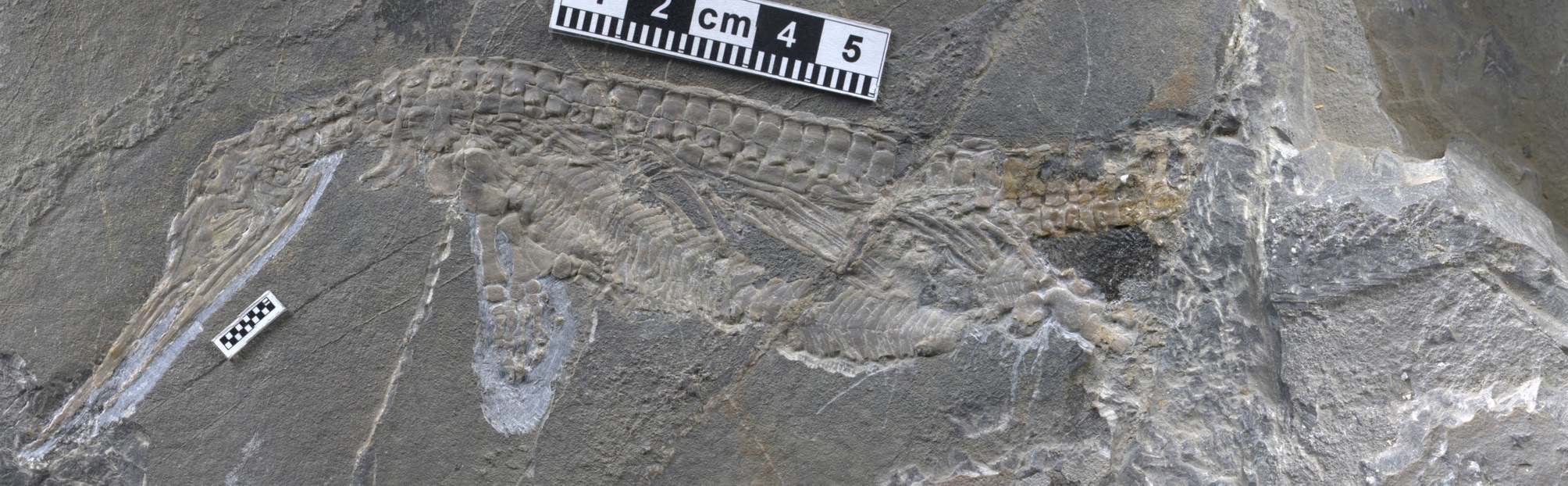

A strange marine reptile from the age of dinosaurs that was recently unearthed in China may shed light on how life recovered after the greatest mass extinction in Earth's history, researchers say.

The research could also give scientists a better understanding of the effects of climate change on the modern environment, investigators added.

The new, 248-million-year-old fossil is a kind of extinct, short-necked marine reptile known as a hupehsuchian. The creatures were odd-looking predators that grew to about 6 feet (2 meters) in size, and have so far only been found in the province of Hubei in central China. Their name derives from "hupeh," an alternative spelling of Hubei, and "suchus," the Greek name for the Egyptian crocodile deity Sobek.

"Hupehsuchia is a group of bizarre marine reptiles unlike anything living today," said study co-author Ryosuke Motani, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of California, Davis. "They had a duck like snout without teeth, a robust body protected by thickened bones, and paddle-shaped limbs." [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

Although scientists first discovered hupehsuchians more than 50 years ago, little is known about them, so they are "puzzling paleontologists," Motani said.

Now Motani and his colleagues have discovered the smallest hupehsuchian unearthed yet, which reveals these mysterious reptiles might have diversified more rapidly than previously expected.

The new fossil is named Eohupehsuchus brevicollis, an adult specimen the researchers estimate would have been about 15 inches (40 centimeters) long when it was alive. The researchers discovered it in 2011 during a field excavation in Hubei. The animal apparently lost part of the tip of its front left paddle, possibly in a predator attack, before it was buried.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists explained the name given to species: "Eohupehsuchus" means "dawn hupehsuchian," and "brevicollis" means "short neck."

"The shortness refers to how many neck vertebrae there were," Motani told Live Science. "Hupehsuchia usually had 10 neck bones, while Eohupehsuchus only had about half, six." Overall, the neck of Eohupehsuchus, which was slightly less than 1 inch (2.2 cm) long, took up less of the length of the animal's body, shorter than other hupehsuchians, which had necks that usually ranged from 3 to 4 inches (7.5 to 10 cm) long, he said.

Early reptiles had few neck bones, so the short neck of Eohupehsuchus probably reflects the fact that the creature arose before its longer-necked relatives, Motani said. The longer necks on other, later hupehsuchians evolved "presumably because the added flexibility allowed these animals to capture prey more easily, leading to higher success," he said.

This new fossil suggests that after the biggest die-off in Earth's history — the end-Permian mass extinction, which occurred about 252 million years ago — animals on Earth rebounded faster than thought, Motani said. The cataclysm killed as much as 95 percent of all species on Earth about 4 million years before this specimen of Eohupehsuchus lived.

"I was really not expecting Hupehsuchia to be this diverse," Motani said. "The diversity implies that the recovery from the end-Permian mass extinction may have proceeded faster than generally believed."

Discovering more about how the end-Permian mass extinction and the global warming that accompanied it affected predators "is interesting, given that humans are vertebrate predators facing global warming," Motani said. "There are many more fossils that we have excavated, and even more are still in the mountains and hills to be discovered."

Motani and his colleagues detailed their findings online Dec. 17 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus