Image Gallery: Miniature Human Stomachs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers can now grow miniature human stomachs in a petri dish in just about a month. These tiny stomachs measure less than 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) in diameter, but may be valuable tools in understanding stomach development and diseases, experts say. [Read full story on miniature, lab-grown human stomachs]

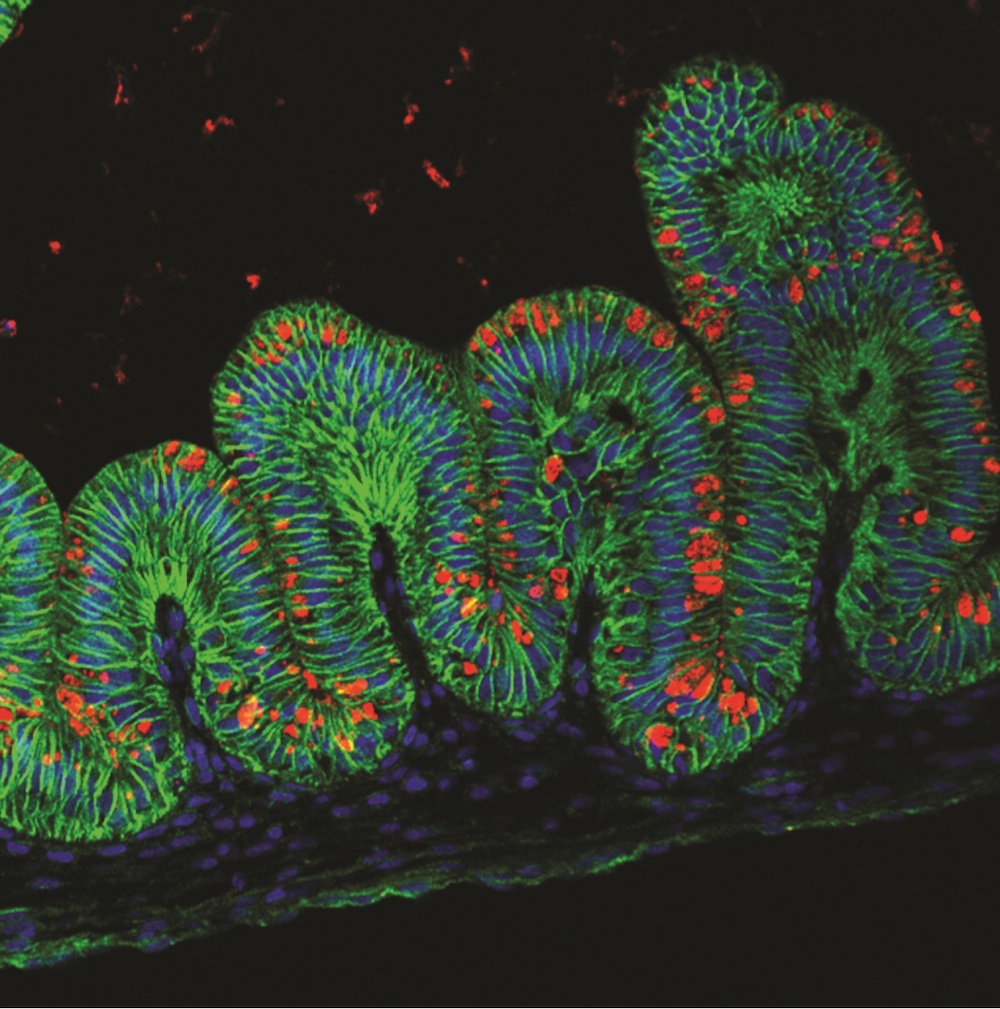

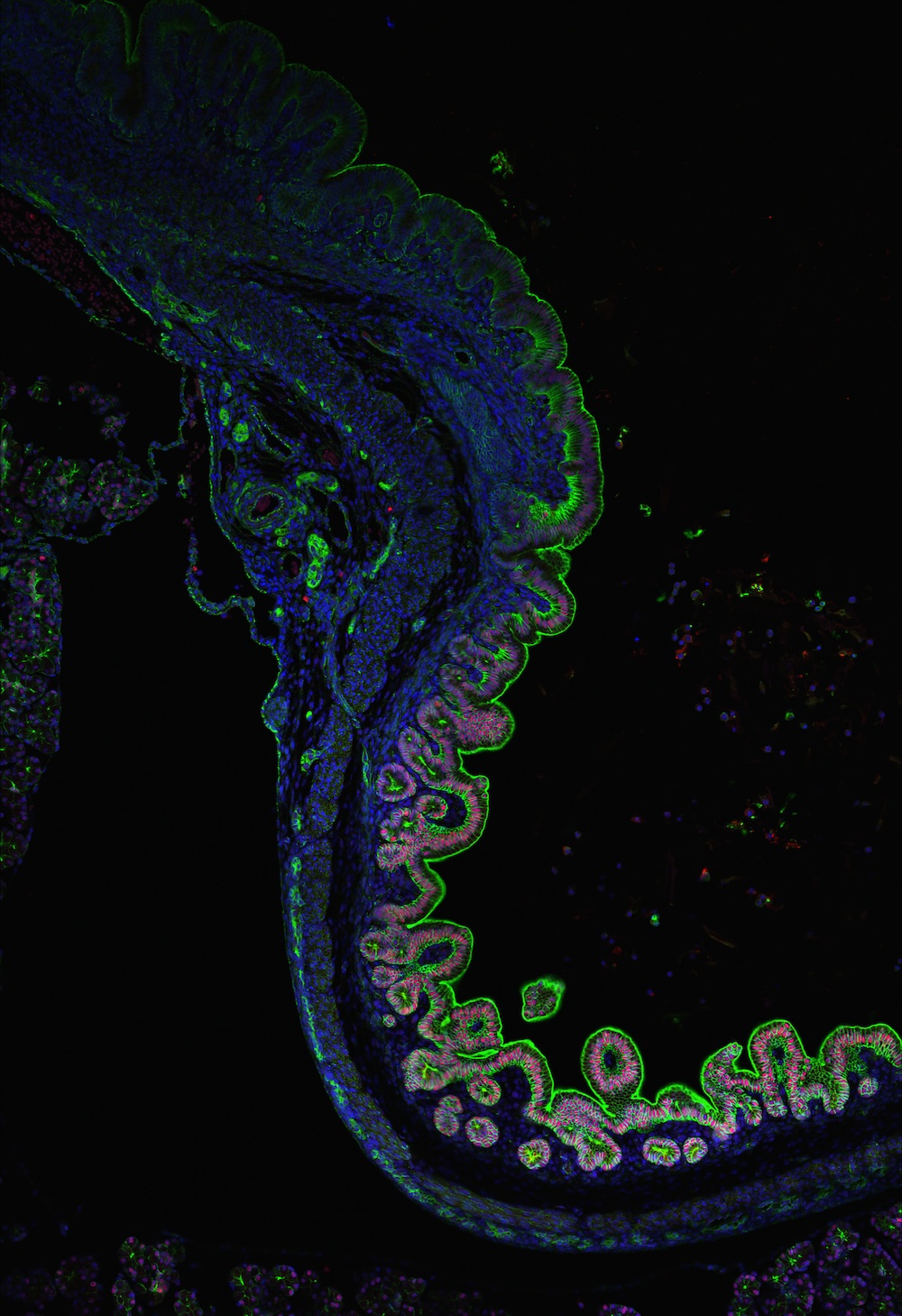

Curvy folds

The tiny, lab-grown stomachs contain folds of tissue, just like a regular human stomach. The glowing green proteins, called E-cadherins, sit on the lining of the stomach. (Photo credit: Kyle McCracken.)

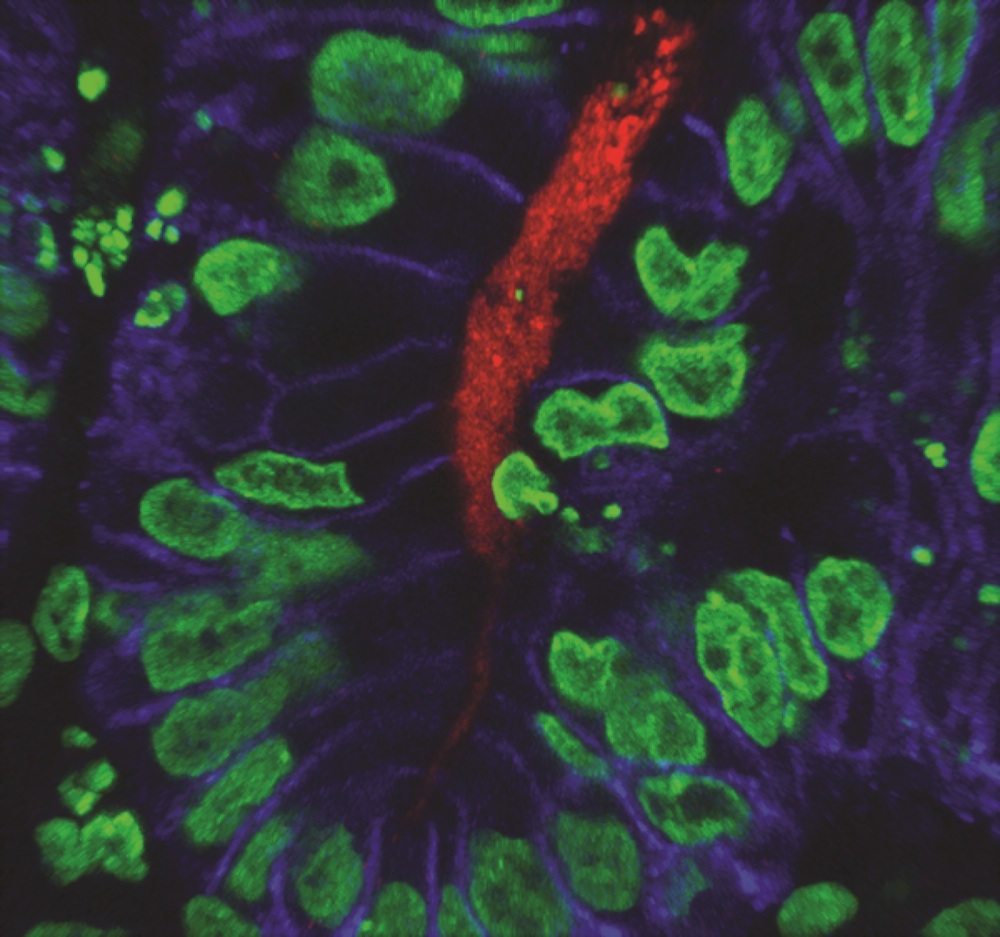

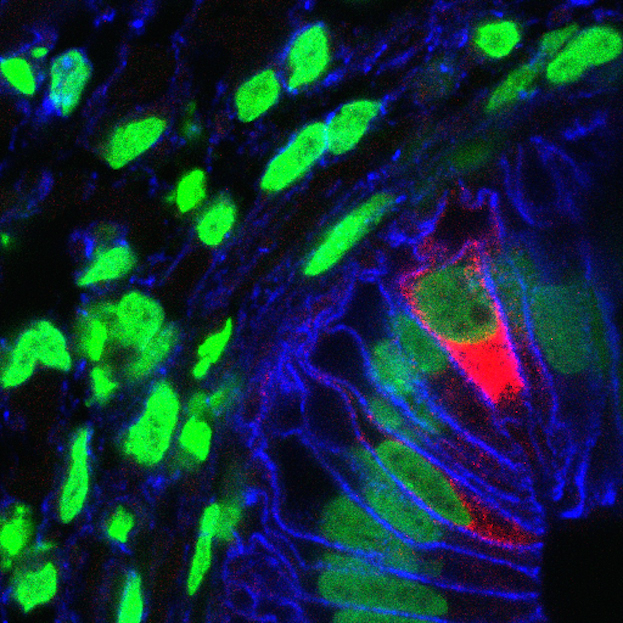

Red spot

The ulcer-causing bacteria H. pylori stands out in red in a section of miniature human stomach grown in a lab. The new, lab-grown stomach may serve as a useful model for researchers studying how to treat chronic H. pylori infections in people, the researchers said. In this image, the E-cadherin protein, which lines stomach tissue, glows in bluish purple. (Photo credit: Kyle McCracken.)

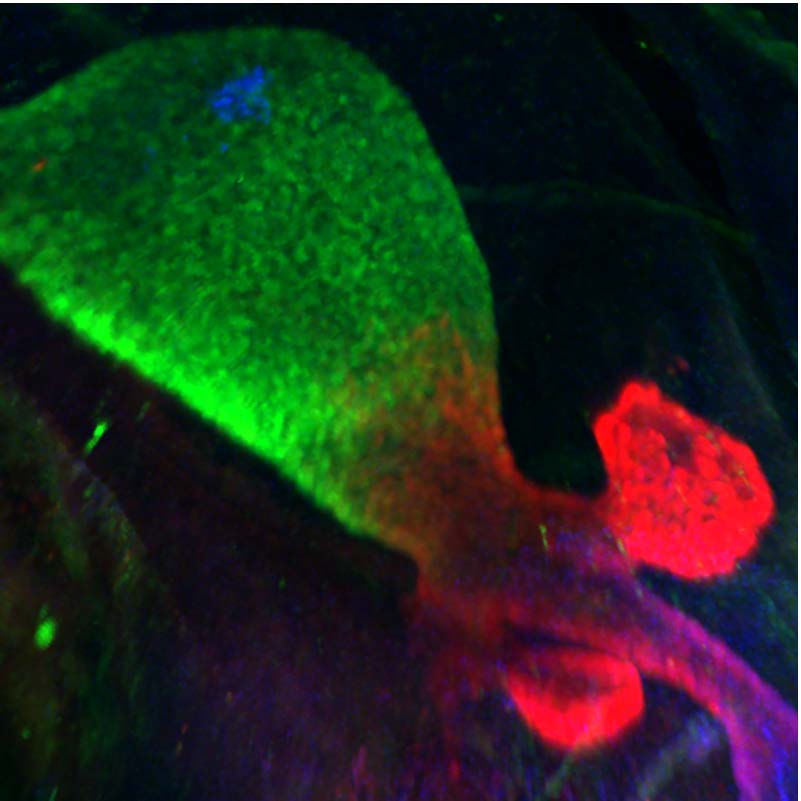

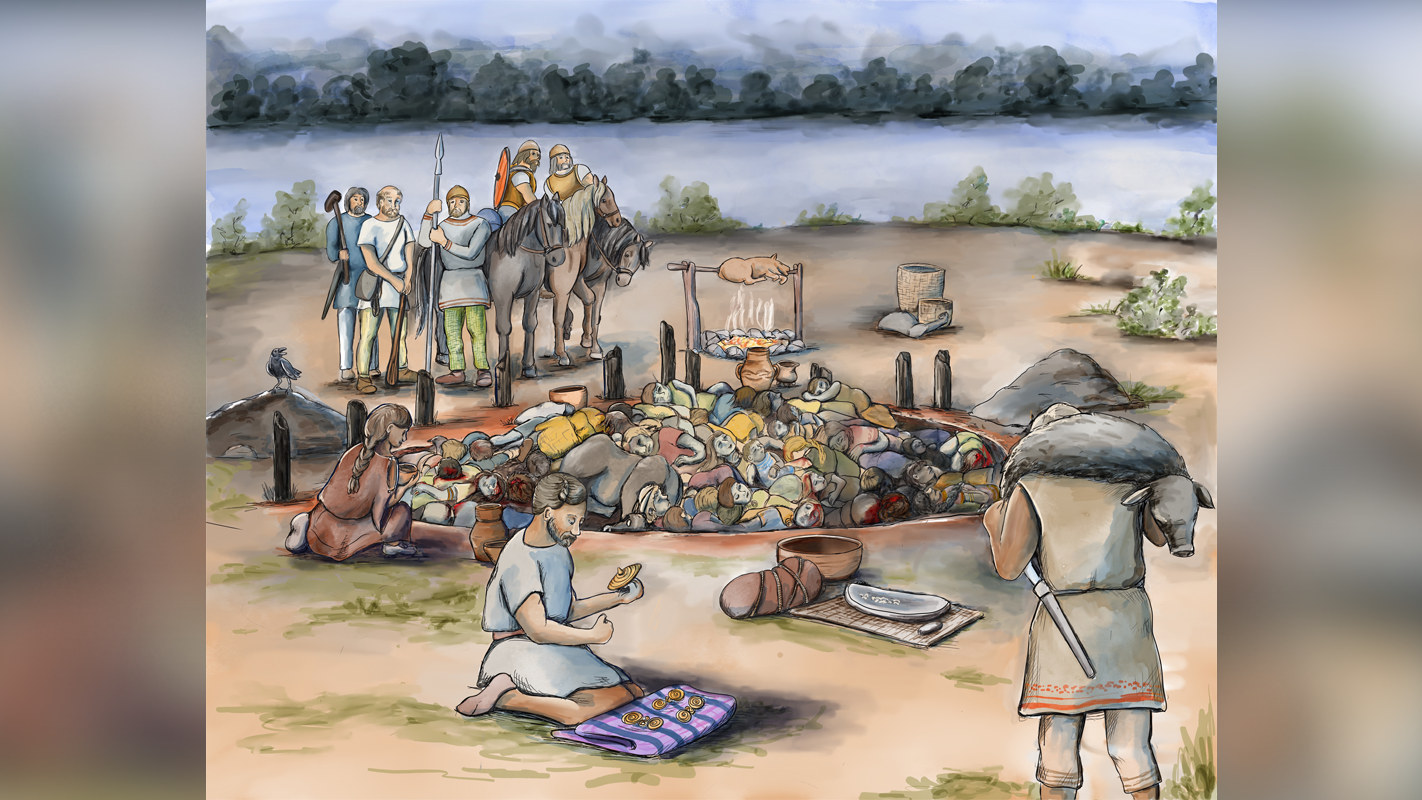

Mouse development

Stomach development is strikingly similar between human and mice. A mouse gut, shown here, confirmed that the lab-grown human stomachs were growing the right way.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Pretty much everything that the mouse stomach was doing during development, our [stomach] organoids were also doing," said researcher Jim Wells, a professor of developmental biology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. "And that told us we were accurately reproducing the normal stages of stomach development." (Photo credit: Katie Sinagoga.)

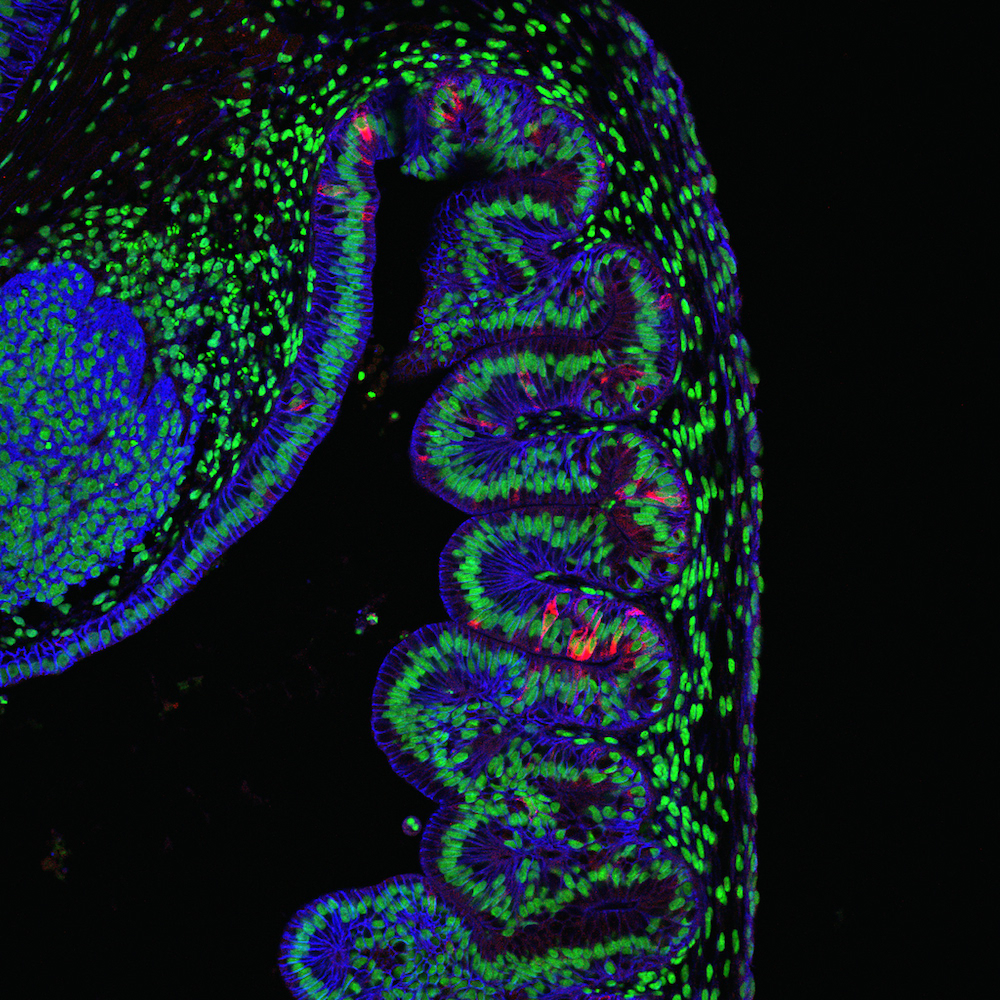

Glowing guts

The tiny stomachs are the first grown from pluripotent human stem cells. They form complex, 3D structures. To make them, the researchers used both basic research and trial and error until they found the right chemical switches to turn on and off during development. (Photo credit: Kyle McCracken.)

Organoid growth

The small stomachs technically aren't organs. Researchers call them organoids, little three-dimensional organlike structures. Other lab-created organoids include the thyroid, brain and intestine. (Photo credit: Kyle McCracken.)

Almost there

The organoids are not complete stomachs, the researchers said. The tissue is a model for the gastric antrum, the part of the stomach that makes proteins that direct functions such as digestive enzyme production. The researchers are now studying ways to make the part of the stomach responsible for acid production. (Photo credit: Kyle McCracken.)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus