Apple Health App: What It Can and Can't Do

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Apple's new Health app is now up and running on the latest version of iOS 8, but what exactly can this app do for you?

The first thing to know is that the Health app doesn't track information by itself, at least not yet. It's an aggregator, meaning it pulls information from your other health apps, and displays it all for you in a single dashboard. So, for Apple's Health app to be useful, you'll need other health apps.

Experts say that aggregation apps like Apple's Health can offer users a new experience while allowing them to keep the apps they've become accustomed to using.

With the Health app, Apple is saying "you don't have to abandon [your old apps], but here's a new experience that you can digest your old data in," said Dan Ledger, principal at consulting firm Endeavour Partners.

Although this aggregation may not be difficult for people who use just two or three apps separately, "there may be opportunities for taking that data, combining it and visualizing it in ways that these stand-alone apps can't do," Ledger said.

Right now, there is a limited selection of apps that work with Apple Health. For example, if you track your activity with a fitness tracker such as a Fitbit, a Withings Pulse or a Basis watch, you're out of luck, because the apps for these devices don't integrate with Apple Health yet.

But quite a few popular apps have already updated their software and do work with Apple Health, including Jawbone UP, MyFitnessPal and Run with Map My Run+.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

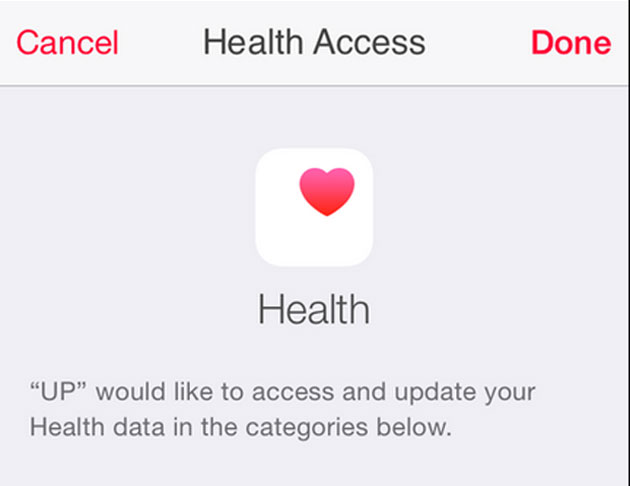

You can allow these apps to "write" data to your Health app, so that your data — like how many steps you take, and how many calories you've eaten — will show up on the Health app dashboard. You can also allow these apps to "read" data from the Apple app, so your different health apps can share information with one another.

Essentially, the Health app serves as a hub, allowing information to come in and go out of a central place. And you can choose which information you want third-party apps to see. [10 Fitness Apps: Which Is Best for Your Personality?]

But how does aggregation offer more of a benefit than tracking things in just one app? After all, the new UP app (which does not require a wristband) already tracks steps, calories burned and sleep, and even has a place to input what you eat.

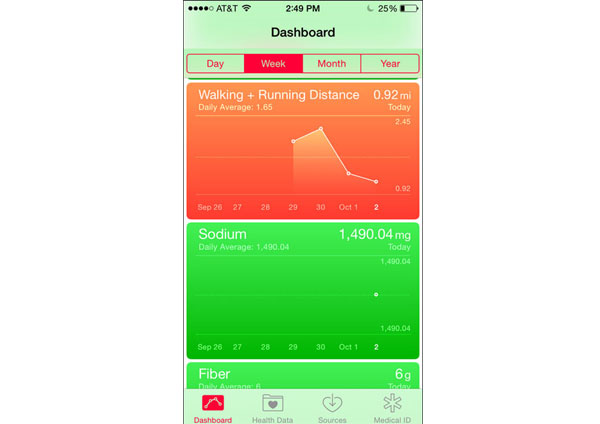

To find out some of the potential benefits of aggregation, I downloaded MyFitnessPal to track my food intake. This app does not show you a graph of the data on individual nutrients over time, but Apple's Health app does. Here's what the graph looks like:

Graphing information for a single nutrient, like sodium, may be a useful way to keep track of whether you're getting too much or too little of it. However, when I tested the app, there seemed to be a few bugs in communication between MyFitnessPal and Apple Health: First, my nutrition data did not show up on the Health dashboard until I restarted my phone and entered my nutrition information again. And second, only one nutrition data point showed up at a time — the app didn't show me a graph of my intake over time.

Ledger said there are other challenges to aggregating information. For example, if you have one app that tracks your workouts and one that tracks your steps, and you go for a run, the apps will have to know that that's one event — which is not an easy problem to solve, Ledger said.

Still, tracker aggregators could help users find connections in their data that they might not notice otherwise, like whether their workout quality changes based on temperature or humidity levels, he said. (However, it's not clear if there's an "app for that" yet.)

Also, right now, the Health app can aggregate a number of measurements from your apps, but it's not an all-inclusive list. For example, there is no place to track menstrual cycles or your exposure to ambient light (which some finesses trackers do track).

In addition, when developers make apps that provide "prescriptive" information about your health — that is, give you advice on how to be healthier — they have to tread carefully because they need to make sure those insights are accurate, Ledger said. As a result, many health apps provide only descriptive information, (i.e., just your stats).

"The biggest challenge right now is getting those insights into an extremely high level of accuracy and reliability," Ledger said. Giving people wrong advice could be harmful, or cause them to distrust the app, even if the app is right most of the time, Ledger said. "It's not about the 80 percent of the time you're going to get it right; it's about the 20 percent of the time you're going to get it wrong," he added.

Another challenge for aggregation is that, to get nutrition insights, users typically have to manually enter what they ate, which takes time, and people don't always remember do it, Ledger said. So even if you could find correlations between what you eat and your activities, you'd have to remember to enter your food information, likely for several weeks, Ledger said.

"If you had data about caffeine intake and sleep, you can begin to correlate caffeine and sleep. But that requires that anytime I have coffee, I go into the app and tell it," Ledger said. "That's a huge [thing to] ask of people."

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLive Science @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus