Greenland Glacier Loses Big Chunk of Ice (Photo)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

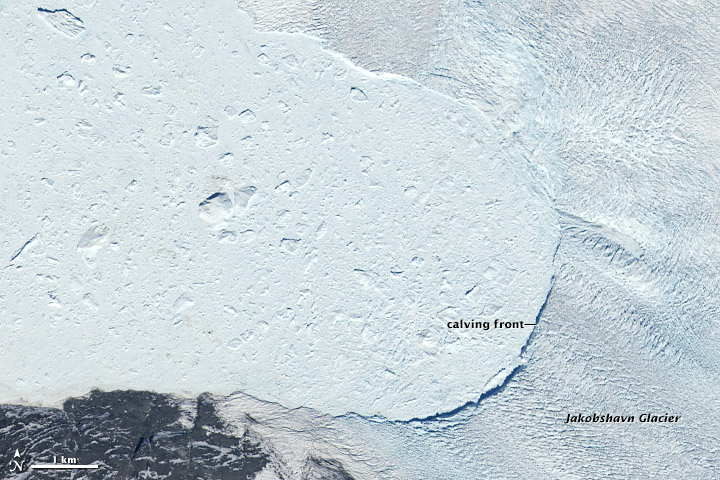

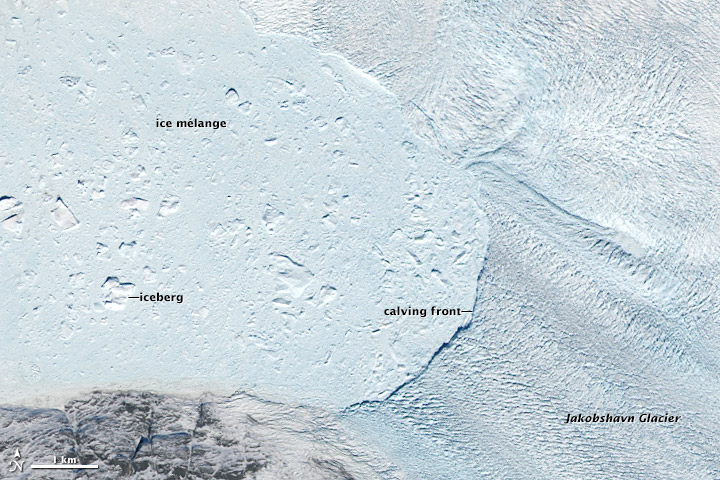

Greenland's Jakobshavn glacier recently made headlines for its record-breakingly fast flow. Now, a new satellite image provides a visual of this process.

In a comparison between two images of the glacier, one taken May 9 and the other June 1, the loss of kilometers of ice from the calving front of the glacier is visible. The change is so significant that the after image almost looks like it has been "zoomed out" to make the glacier look smaller. But the views are the same. The missing ice simply slipped into the sea.

The Jakobshavn glacier is one of Greenland's most prominent. It drains some 6.5 percent of the Greenland ice sheet area into the Ilulissat Icefjord in western Greenland, according to NASA. Researchers believe this glacier produced the iceberg that wrecked the Titanic. [Gallery: Greenland's Melting Glaciers]

Speedy glacier

In February, a study in the journal The Cryosphere found that the Jakobshavn conveyer belt that moves ice from the ice sheet to the ocean is churning faster than ever. In the summer of 2012, the study found, the glacier moved 151 feet (46 meters) per day, or the equivalent of more than 10.5 miles (17 kilometers) a year.

"We are now seeing summer speeds more than four times what they were in the 1990s on a glacier, which at that time was believed to be one of the fastest, if not the fastest, glacier in Greenland," study researcher Ian Joughin of the University of Washington Polar Science Center said in a statement at the time.

Between 2000 and 2010, the Jakobshavn glacier's shed ice raised sea levels by 0.04 inches (1 millimeter), Joughin added, an impressive feat for a single glacier. As the glacier flows and thins, its calving front — where ice meets sea — is retreating, meaning that the glacier now drops ice farther inland than it used to. In 2012 and 2013, Joughin and his colleagues found that the calving front retreated 0.6 miles (1 km) inland compared with previous summers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Icy visuals

This sort of retreat is visible in these satellite images, both taken by NASA's Landsat 8 and released by NASA's Earth Observatory. The striated, almost scaly ice of the glacier is seen on the right of the photographs. To the left, a frothy-looking icy mélange floats in the fjord. The chunks in this mélange are large icebergs. In the few weeks between the two views, a massive amount of ice has calved off the glacier.

Though this calving event was not caught on camera, others at the Jakobshavn glacier have been. In 2008, the Extreme Ice Survey team, led by photographer James Balog, captured a calving event on film that lasted some 75 minutes. Two videographers camped out for weeks waiting to see Jakobshavn drop ice. They were rewarded with the largest calving ever caught on film — and a view of a chunk of ice as wide as Manhattan falling into the fjord. The footage can be seen in the 2012 documentary "Chasing Ice."

Meanwhile, the rest of Greenland is seeing massive ice loss as well. In March, researchers reported that the northeast Greenland ice sheet, long thought to be relatively protected from warming, has lost more than 10 billion tons of ice each year since 2003.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing nature or general science photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus